|

|

||

|

|||

George Will warns Class of 2003 against historical amnesia

|

|

|

|

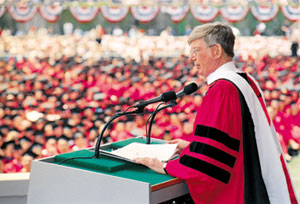

George Will delivers the Commencement address on May 18. Photo by Albert L'Etoile |

|

George Will’s speech at BU’s 2003 Commencement was full

of baseball stories. Although Will is a political columnist, that should

not be surprising, because the self-professed baseball addict admits

that the sport “is always on my mind. I write about politics primarily

to support my baseball habit.”

Still, “the national pastime,

properly understood, is rich with pertinent lessons for the nation,” he

said. He warned graduates against “historical amnesia,” citing

the integration of major league baseball as an example: in 1947, with

the help of the late black

sportswriter Sam Lacy, Jackie Robinson became the first African-American

player in the major leagues. Will went on to say that Robinson rose to

the top on talent. It is a lesson, he said, that the Supreme Court should

consider in the next few weeks when it rules on whether or not giving

preferential treatment to minorities in college admissions is constitutional.

“

The lives of Sam Lacy and Jackie Robinson remind us that a core principle

of an open society is careers open to talents,” he said. “Open

to individuals, without interference — and without favoritism.”

Will

began the sun-splashed ceremony on May 18 with humor. Before his speech

to more than 5,000 graduates and 20,000 guests, he commented on

a bizarre play that had taken place during a Red Sox game the previous

day. “Before I begin, are there any mathematics majors here?” he

asked. “The Red Sox ask you to report to Fenway Park after this

ceremony to teach Trot Nixon to count to three.” Thinking there

were three outs instead of two, the Red Sox rightfielder unwittingly

threw a ball he had caught into the stands, allowing a crucial run to

score.

But Will later spoke about another Red Sox miscalculation, this

one more pernicious: not signing Jackie Robinson when they had the chance.

Robinson

had a tryout at Fenway Park in 1945, to no avail. In a “bitter-end

resistance to integration,” the Red Sox official responsible for

signing players wouldn’t show up. (The Red Sox were the last team

to field an African-American player.) The attitude cost the franchise

dearly.

“

The Red Sox suffered condign punishment for their bad behavior,” he

said. “In 1946 they lost the seventh game of the World Series.

In 1948 and 1949 they lost the American League pennant on the last day

of the season. The Red Sox might have won a World Series and two pennants

with Jackie Robinson in the lineup.”

What follows are excerpts from

Will’s speech. The complete text

can be found at www.bu.edu/news and in the summer issue of Bostonia,

due out at the end of June.

• • •

Of course baseball, the national pastime, like the nation itself, had

a long history of racism. And then Sam Lacy stepped, as it were, to the

plate.

Lacy, whose father was African-American and whose mother was a

Shinnecock Indian, was born in Mystic, Connecticut, but grew up in Washington,

D.C.,

which was then a very Southern, very segregated city. He became a baseball

fan. A fan of the Negro leagues, of course, but also of the old Washington

Senators, which was not easy at a time when the saying was “Washington:

first in war, first in peace, and last in the American League.”

How

bad were the Senators? Their owner, Clark Griffith, once said, “Fans

like home runs, and we have assembled a pitching staff to please our

fans.”

Nevertheless, Sam Lacy loved the Senators, and loved major

league baseball, even though African-Americans were excluded from its

playing fields,

and in Washington — as in St. Louis — they were confined

to segregated sections of the stands. He hung out at the Senators’ ballpark,

shagging flies, running errands for the players, and working as a vendor

in the stands.

After graduating from Howard University, Sam Lacy became

a sportswriter for African-American newspapers, first, in 1930, at the

Washington Tribune,

then in Chicago, and after 1943, in Baltimore. He became a tireless advocate

for the integration of major league baseball. Writing columns, writing

letters, he prodded baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis.

Landis,

who was named after the site of a Civil War battle, was a Confederate

at heart, and was hostile to Sam Lacy’s pressure. But Lacy persisted,

contacting people in major league baseball who he thought might be sympathetic,

including Branch Rickey of the Dodgers.

In 1945 Lacy wrote: “Baseball

has given employment to known epileptics, kleptomaniacs, and a generous

scattering of saints and sinners. A man

who is totally lacking in character has turned out to be a star in baseball.

A man whose skin is white or red or yellow has been acceptable. But a

man whose character may be of the highest and whose ability may be Ruthian

has been barred completely from the sport because he is colored.”

Notice

Lacy’s use of the word character. Lacy knew that the first

black big leaguer would need exceptional talent — and even more exceptional

character.

Early on Lacy focused on an African-American player who by

1940 had established himself as one of the greatest all-around athletes

America had ever seen.

This athlete became the first man at UCLA to letter in four sports. In

football, as a junior he led the Pacific Coast Conference in rushing,

averaging 11 yards a carry. Yes, 11 yards.

He also led the conference

in scoring in basketball. Twice.

On the track team he won the NCAA broad

jump championship. He dabbled at golf and swimming, winning championships

in both.

And he could play a little baseball.

His name was Jackie Roosevelt Robinson.

By 1945 he was playing baseball

in the Negro leagues. Lacy was one of those who advised Branch Rickey

that Robinson had the temperament to

play the demanding game of baseball with poise even while enduring the

predictable pressures and abuse of a racial pioneer.

But before the color

line was erased in Brooklyn, Lacy and others tried to get it erased in

Boston.

The Boston Braves were, almost always, dreadful. In fact, in the

1930s a new owner thought a change of name might improve the team’s

luck. Fans were invited to suggest names — and suggested the Boston

Bankrupts

and the Boston Basements. The newspaper people judging the suggested

names picked the Boston Bees, primarily because a short name would simplify

writing headlines. And the Bees they were for several years, before again

becoming the Braves.

But because the Braves were so bad, they would at

least listen to a good idea.

In 1935 a Boston civil rights pioneer, an

African-American, approached both the Braves and Red Sox about hiring

an African-American player.

The Red Sox gave him short shrift. The Braves, too, ultimately flinched

from challenging the major leagues’ color line — but because

the Braves were so awful, they took the idea seriously.

Notice what was

stirring. Competition concentrates the mind on essentials.

Sport is the competitive pursuit of excellence. The teams most in need

of excellence were the ones most receptive to the idea that baseball

should be color-blind.

Consider the case of Boston’s other team.

Boston has always been

an American League city. So the Red Sox were more complacent than the

Braves. Hence the Red Sox were less receptive to

the wholesome radicalism of the nascent civil rights movement.

But in

1945 a member of Boston’s city council threatened that if

the Boston teams continued to resist the integration efforts of Sam Lacy

and others, he, the city councilman, would block the annual renewal of

the license that allowed the Braves and Red Sox to play on Sundays.

The

Red Sox replied, with breathtaking disingenuousness, that no African-Americans

had ever asked to play for them and none probably wanted to because they

could make more money in the Negro leagues. The city councilman enlisted

the help of a journalistic colleague of Sam Lacy and brought three African-American

players to Boston for a workout at Fenway Park on an off-day.

One of them

was Sam Jethroe, an outfielder who later would play here, for the Braves.

Another was Jackie Robinson. The Red Sox official responsible

for signing players would not even attend the workout.

At the end of the

workout a voice from deep in the Fenway Park stands shouted, “Get

those niggers off the field!” It was 14 more

years — 1959 — before the Red Sox finally fielded an African-American

player, Pumpsie Green. At that time there were just 16 major league teams.

The Red Sox were the 16th to integrate.

During their bitter-end resistance

to integration the Red Sox sent a scout to Birmingham, Alabama, to look

at an outfielder playing for the

Birmingham Black Barons. The scout reported laconically that the outfielder

was not the Red Sox kind of player. The scout was right about that. The

outfielder was Willie Mays. . . .

The national pastime was integrated

in 1947, a year before the nation’s

military abolished segregated units. But 3 years before that — 11

years before Rosa Parks refused to move to the back of a segregated bus

in

Montgomery, Alabama — Lt. Jackie Robinson of the United States

Army was court-martialed for refusing, at Fort Hood, Texas, to obey a

bus

driver’s orders to move to the back of a segregated bus. Jackie

Robinson was acquitted.

It is instructive that the two most thoroughly

and successfully integrated spheres of American life are professional

sports and the military. This

is, I submit, related to the fact that both are severe meritocracies.

The

military is meritocratic because competence and excellence are matters

of life and death — for individuals and for nations. Sports are

meritocratic because competence and excellence are measured relentlessly,

play-by-play,

day-by-day, in wins and losses. Particularly in baseball, the sport of

the box score, that cold retrospective eye of the morning after.

Today

the principle that individuals should be judged on their individual merits,

not on their membership in this or that group, is still under

attack. The attack is against a core principle of an open society — the

principle of careers open to talents. Today there are pernicious new

arguments for treating certain groups of Americans as incapable of

doing what Sam Lacy knew Jackie Robinson could do: compete.

Sometime in

the next few weeks the Supreme Court, in a case rising from the University

of Michigan, will rule on the question of whether racial

preferences in college admissions are compatible with the constitutional

requirement of equal protection of the laws for all individuals. The

argument about racial preferences is another stage — in my judgment,

another deplorable detour — on our long national march toward a

color-blind society.

The lives of Sam Lacy and Jackie Robinson remind

us that a core principle

of an open society is indeed careers open to talents. Open to individuals,

without interference — and without favoritism.

It is no accident

that baseball was central to the lives of Lacy and Robinson, and to their

crusade for a meritocratic society blind to color.

Baseball’s season, like life, is long — 162 games, 1,458

innings. In the end, the cream rises — quality tells.

Quality told

in April 1946, when Jackie Robinson went to spring training with the

Montreal Royals, the Dodgers’ highest minor league affiliate.

In an exhibition game he faced a veteran pitcher, a Kentuckian, who thought

he would test Robinson’s grit by throwing a fastball at his head.

Robinson sprawled in the dirt, then picked himself up, dusted himself

off, and lashed the next pitch for a single.

The next time Robinson came

to bat, the Kentuckian again threw at Robinson’s

head. Again, Robinson hit the dirt. And then he hit the next pitch. Crushed

it, for a triple.

After the game the Kentucky pitcher went to Robinson’s

manager, another Southerner, and said simply, one Southerner to another: “Your

colored boy is going to do all right.”

He did more than all right.

Jackie Robinson became 1947’s Rookie

of the Year, en route to the Hall of Fame.

In 1948, Sam Lacy became the

first African-American member of the Baseball Writers Association of

America. And in 1997, the day before he turned

94, he was inducted into the writers and broadcasters wing of the Baseball

Hall of Fame. So Sam and Jackie will forever be, as it were, teammates

in Cooperstown.

• • •

![]()

6

June 2003

Boston University

Office of University Relations