|

|

||

|

|||

Newly

posted to Special Collections

Sentiments both cold and warm found in letters of Somerset Maugham

By David J. Craig

In letters to the portrait painter Sir Gerald Kelly, W. Somerset Maugham (1874–1965) was often philosophical and didactic, offering blunt opinions about the sacrifices required of a serious artist. Writing to his longtime companion Alan Searle, on the other hand, the British novelist could be downright paternal, gently assuring the young social worker that he need not hide his humble background from Maugham’s wealthy friends. Meanwhile, in chatty notes about his world travels to the British socialite Lady Juliet Duff, Maugham’s wit shone through.

|

|

|

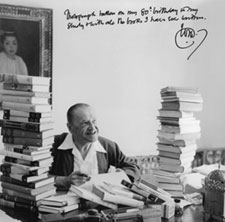

| The British author W. Somerset Maugham (1874–1965) was remarkably prolific, publishing 20 novels, 13 short story collections, and 24 plays, as well as several travel books, memoirs, and essay collections. He is pictured here on his 80th birthday, surrounded by all his books. An important archive of Maugham’s papers, including original manuscripts and hundreds of personal letters, was acquired recently by BU’s Special Collections from Loren and Frances Rothschild. Photo by Jack Eston |

|

“Maugham took on very different temperaments depending on whom

he was corresponding with, but he always came across as being aware that

he was someone to be reckoned with,” says Howard Gotlieb, director

of BU’s Special Collections, which earlier this year acquired the

large private Maugham archive of collectors Loren and Frances Rothschild.

“He knew he was a great man.”

The collection features hundreds of letters chronicling the author’s

private and intellectual life, as well as handwritten manuscripts and

first editions of several of his novels and short stories, a 1951 bust

of Maugham by the prominent British sculptor Sir Jacob Epstein, photographs,

audiovisual material, and other artwork and ephemera. Highlights from

the collection are on display for the next year on the fifth floor of

Mugar Memorial Library at 771 Commonwealth Ave. The exhibition is free

and open to the public.

In 1998, Special Collections acquired at auction another large holding

of Maugham papers and memorabilia, mostly from his Cap Ferrat home in

southern France, so the Rothschild acquisition gives BU one of the “most

complete literary archives of a single author” in existence, says

Gotlieb.

“The collection we acquired in 1998 contained Maugham’s birth

certificate, report cards, death certificate, address books and journals,

and many letters addressed to Maugham,” he says. “Added to

that material, the Rothschild collection, which contains hundreds of letters

written by Maugham, gives us an incredible archive that will provide interesting

subjects for literary researchers for many years.

“Everybody bought Maugham and everybody read Maugham because he

was a great storyteller, which not all novelists are,” Gotlieb continues.

“He told a beautiful story, and that is why he is what one might

call a classical author, and that is why his work is not transitory. He

was one of the true literary giants of the 20th century, and his books

will prove to have a lasting quality.”

BU Chancellor John Silber says that Loren Rothschild, the founder and

president of a private investment firm in Los Angeles, and his wife, Frances,

a Los Angeles County Superior Court judge, built their Maugham archive

over the past 25 years “with remarkable intelligence, taste, and

tenacity. . . . After the period of eclipse which often follows popular

success, the stature of W. Somerset Maugham is once again being increasingly

recognized. Boston University’s already substantial Maugham holdings

have long been an important resource for Maugham scholars. Now, with the

acquisition of the Rothschild Maugham Collection, the importance of the

Maugham holdings has been greatly magnified.”

|

|

| Loren and Frances Rothschild. Photo courtesy of the Rothschilds | |

Author of the classic bildungsroman novel Of Human Bondage (1915) and

the short story collection Ashendon (1928), which was based on his experiences

as a secret agent during World War I and is considered the first work

of contemporary spy fiction, Maugham was one of the world’s richest

and most popular writers in the 1930s. He endured a critical backlash

in the late 1930s -- many in the literary establishment accused him of

churning out lightweight yarns that said little about the human condition

-- but his books have remained popular, especially in the United States.

He also was remarkably prolific, publishing 20 novels, 13 short story

collections, and 24 plays, as well as several travel books, memoirs, and

essay collections “It is enough for a novelist to be a good novelist,”

Maugham said in a speech upon presenting the manuscript for Of Human Bondage

to the U.S. Library of Congress in 1946. “It is unnecessary for

him to be a prophet, a preacher, a politician, or a leader of thought.

Fiction is an art and a purpose of art is to please. If in many quarters

this is not acknowledged, I can only suppose it is because of the unfortunate

impression so widely held that there is something shameful in pleasure.

I venture to put the reading of a good novel among the most intelligent

pleasures that a man can enjoy.”

Maugham’s handwritten notes for that speech, including occasional

edits in red ink, are part of the Rothschild Maugham Collection and are

among the items being displayed at Special Collections. Other remarkable

pieces in the collection are a letter to James Bond creator Ian Fleming,

in which Maugham compliments the less-polished young author on how he

handled particular scenes in Moonraker, and a vitriolic 11-page letter

to his wife, Syrie, in 1920, in which Maugham explains why he no longer

loves her.

Gotlieb, who founded Special Collections 40 years ago, says BU’s

Maugham archive now joins the papers of H.G. Wells, George Bernard Shaw,

Osbert Sitwell, Theodore Roosevelt, Robert Frost, Martin Luther King,

Jr., Fred Astaire, and Bette Davis as one of his department’s “prize

collections.” It currently is being used by Lady Selina Hastings,

the author of Evelyn Waugh: A Biography, who is writing Maugham’s

official biography.

Loren Rothschild, who had gone “head-to-head” with BU for

Maugham material at auctions in the past, says that upon deciding to divest

himself of his archive last year, he contacted Gotlieb because he thought

BU was “the right place” for the collection.

For more information about Special Collections, including exhibition hours, visit www.bu.edu/speccol.

![]()

6 December 2002

Boston University

Office of University Relations