![]()

Departments

![]()

|

13 August 1999 |

Vol. III, No. 3 |

Feature Article

Law prof wants tougher laws to fight hate crimes

By David J. Craig

The murders of Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr., last year were among the most brutal crimes in recent U.S. history. But were the grisly killings worse because the perpetrators were motivated by the fact that Shepard was gay and Byrd was black?

Absolutely, according to LAW Professor Frederick Lawrence, who argues in a new book in favor of so-called hate crime laws, which mandate stiffer sentences for criminals who act out of bigotry. Punishing Hate: Bias Crimes Under American Law was recently published by Harvard University Press.

"A physical attack harms the body," Lawrence says. "A bias crime harms the spirit and soul. Bias crimes are also worse than otherwise similar crimes because members of the target community are directly affected, and they often show a great sense of withdrawal and separation from society. And bias crimes impact society at large."

|

|

|

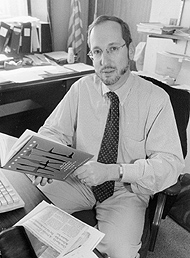

BU Law Professor Frederick Lawrence believes

that criminals who act out of bigotry should be

punished more severely than those who commit

otherwise similar crimes. Photo

by Vernon Doucette

|

In Punishing Hate, Lawrence acknowledges that hate crime laws should be limited in scope so that a criminal who acts out of latent, unconscious racism, for instance, is not prosecuted under such laws.

But he also argues that an expanded federal role in the prosecution of hate crimes is needed to combat the sorts of crimes that left Shepard and Byrd dead, and frightened and angered people across the nation.

"You want a national commitment shown to this because the truth is that some states put more into fighting bias crimes than others," says Lawrence. "And [an enhanced federal hate crime law] would be a tremendous signal to the victim communities that the harm they feel is real. It would be a statement that we do treat these crimes differently."

Currently it is a federal offense to assault a person based on his or her race, color, religion, or national origin. However, eight states have no hate crimes laws, and only about half of those that do cover sexual orientation, gender, and disability in their laws.

James Jacobs, a law professor at New York University, thinks the cost of enforcing the proposed federal legislation would derail other federal priorities such as combating organized crime, terrorism, and counterfeiting. He argues in his book Hate Crimes that such laws also enforce racial divides.

Lawrence disagrees. "My response has always been that it's like not going to the doctor because you're afraid you might find out you're sick," he says. "I don't doubt that when we talk about a crime being racially motivated, we enflame passions. But the alternative is to sweep it under the rug."

While the federal bill is generally supported by minority organizations, hate crime laws remain a controversial issue even among minorities and homosexuals. COM Adjunct Professor of Journalism David Brudnoy, who is homosexual but whose radio talk show and libertarian writing cut across the grain of modern identity politics, called the bill "monumentally foolish" in a Boston Herald column last fall.

"The seriousness of a crime ought to be determined by its unique circumstances, not by the group to which a victim belongs," Brudnoy wrote. "Either the law is blind to incidentals like one's sexual orientation or the law isn't."

Lawrence, however, believes that hate crimes transcend the individuals directly involved.

"It makes me think of the Civil War movie Shenandoah," he says. "At first the family keeps insisting, 'We're not in the Civil War.' But by the end of the play, two of their sons are dead. So you can say you're not a part of this, but the fact is that the person who is attacked because he's gay is not the only victim. The community and the society are affected too.

"That turns out to be the same whether or not the victim was actually gay," Lawrence continues. "The mental state of the criminal is what's important. He's being punished not because his victim was gay, but because his motivation was more harmful and dangerous."

Lawrence has taught at BU since 1988; he became interested in bias crime law while an assistant U.S. attorney in New York, where he worked for five years and prosecuted several police brutality cases that he says had racial overtones.

He says that his personal identity as a Jew helps him empathize with victims of hate crimes, as well.

"I'm an observant Jew, and my interest in this does have something to do with feeling the pain of a minority group and understanding when someone else in one's community is tormented because of an identity," he says. "You're affected in a deeper way.

"I can tell you that the individual victims perceive it that way," he continues. "The only question is if the community is going to validate that harm."