![]()

Departments

![]()

|

Week of 16 April, 1999 |

Vol. II, No. 31 |

Feature

Article

BU scholars grace Hemingway centennial

By Eric McHenry

An international who's who of scholars and writers assembled at the John F. Kennedy Library and Museum April 10 and 11 for the Hemingway Centennial conference, and none of the weekend's events generated more interest than a plenary session whose participants included both of BU's Nobel laureates in literature, Saul Bellow and Derek Walcott. They joined Susan Cheever, Francine Prose, and moderator Henry Louis Gates, Jr., in a discussion of The Canon Before and After Hemingway.

For the most part, however, the panel disregarded any sense of obligation to the topic, resulting in a series of idiosyncratic riffs that revealed the very particular nature of each author's attachment to Ernest Hemingway. Prose seemed to speak for all the participants when she said, "I feel a little bit disingenuous talking about the canon. Writers are more likely to talk about whose work is beautiful, interesting, moving, useful, influential, whose work changed us, whose work we've reacted against. And it is in that context that I'd rather talk about Hemingway."

|

|

|

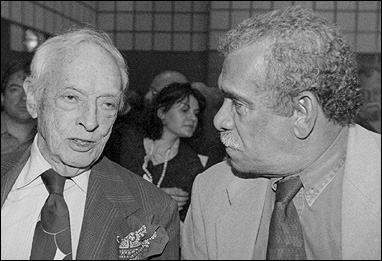

BU's Nobel Laureates Saul Bellow (left) and Derek Walcott confer before their panel discussion at the Hemingway Centennial. Photo by Kalman Zabarsky |

Bellow, a UNI professor, built his case around a quote from Delmore Schwartz, who observed that ". . . the moral code in Hemingway is unmistakable. The rules of the code require honesty, sincerity, self-control, skill, and above all personal courage. . . . It is a sportsmanlike morality which dictates a particular kind of carriage, grand manners and manners of speech."

"It is only natural that literature should provide the models for desirable types of manhood," Bellow remarked. "The more jumbled and disorderly the life surrounding us becomes, the more strongly ideas of order appeal to persons threatened by formlessness. Writers have in the past been charged with a special responsibility to create the most desirable and the most pleasing forms of personality."

Hemingway used the distinctive speech of his characters to accomplish this, said Bellow, buttressing the arguments of many literary scholars who have concluded that the singular achievement in Hemingway's fiction is its dialogue.

"This sportsman morality results finally in a clear, bony, hard, and elegant way of speaking," he said. "Those who live by the code also speak especially well. They honor their beliefs by their manner of speech. . . . If you don't observe the code, or if you are only dimly aware of it, you can't really speak comme il faut."

Walcott, a CAS professor of creative writing, also spoke of the dignity of bearing that is central to Hemingway's writing and that has left more of a mark on literature than any of its rough edges. Intermingling personal anecdotes and prose passages, he illustrated his sense of "Hemingway as a poet." Walcott's first story was set in Jamaica, "many years ago," on a night when he and two writer friends were having drinks and talking about their craft.

"And we got so drunk and so excited talking about Hemingway that we decided to go and see him," Walcott said. "We were in Jamaica. That didn't seem important at the time. We thought, we've got to go and see Papa now. Let's go."

The vague plan they ultimately formulated, which of course they were never able to carry out, involved catching a late-night flight and presenting themselves at Hemingway's door as three admirers of his work.

"We didn't expect to get shot or chased by dogs or prevented from coming in," Walcott said, "because we genuinely thought that if we went to visit Hemingway he would receive us courteously. And I think that is true. I think that is there in his work. His tenderness, his affection, his respect, his kindness to writers is there."

Like the other panelists, Walcott acknowledged that there are racism, misogyny, anti-Semitism, and other sorts of intolerance in much of Hemingway's writing. But great authors such as Hemingway, he said, produce writing that transcends what is invidious in their era, their education, and even their own disposition.

"So much of his writing is racist," Walcott said of Hemingway, "if you want to use that kind of word, although that's a very easy word to use these days. . . . How do you forgive that, or do you think of it at all? That's a big question. And that doesn't obsess me. It doesn't bother me. There are things that are intolerable in Hemingway, but there is so much that is forgivable in him. I think the quality I'm talking about is really Hemingway as a poet."

This characterization set up a sustained treatment of measure in Hemingway. Just as the humanity of his novels transcends their human failings, so does his best prose transcend that designation of genre. Walcott read a passage from Death in the Afternoon, dwelling upon such clauses as "that shines on steel of bayonets freshly oiled."

"It arrives," he said, "at a pentametrical rhythm without being verse. It arrives at that rhythm with the intention of functioning as prose."

Walcott called this an "achievement superior to anything in poetry -- I include Pound, I include Eliot, and I include Auden. You cannot align it with the verse of Frost. You cannot align it with anything experimental, even syllabically with Whitman. This is the work of a poet who has arrived at originality at great cost. And finally, it comes into an ease that is the ease present in Troilus and Cressida or any one of the great plays."

The conference, which honored the centenary of Hemingway's birth, featured keynote addresses by Nobel Laureates Nadine Gordimer and Kenzaburo Oe, both novelists, and Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Maxine Kumin. Other panels included such distinguished authors as Chinua Achebe, Tobias Wolff, Robert Stone, E. Annie Proulx, and Leslie Epstein, CAS professor of English.

For more information about events at the John F. Kennedy Library and Museum, visit its Web site at http://www.cs.umb.edu/jfklibrary/index.htm.