Physical Distancing Policies Not Enough to Protect Lower-Income People.

Physical Distancing Policies Are Not Enough to Protect Lower-Income People

Lower-income people haven’t been ignoring the need to distance, but are much more likely to need to go in to work—which means shutdowns alone aren’t enough.

Physical distancing (also called social distancing) has been the main tool in the US’s response to COVID-19.

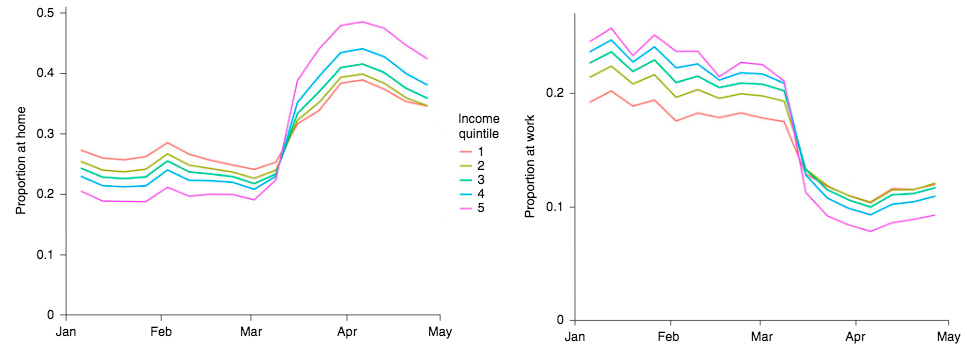

Now, a new School of Public Health study of the first four months of America’s coronavirus epidemic, published in the journal Nature Human Behaviour, shows that these policies had little effect on lower income people still needing to leave their homes to go to work—but does show them staying home when they could.

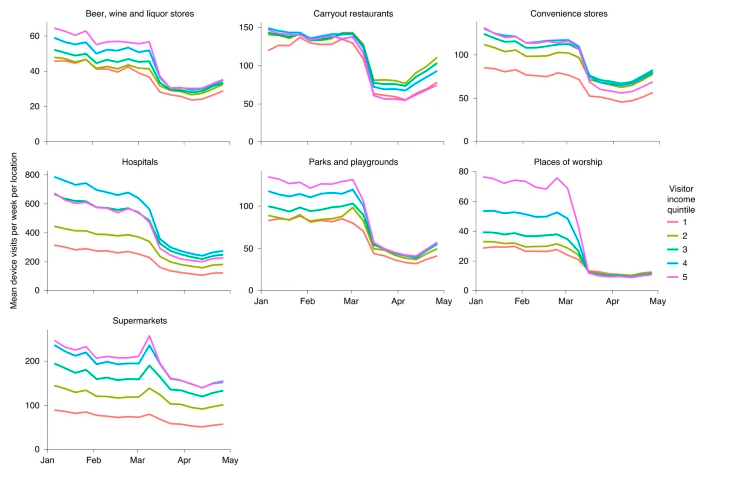

“If lower-income people were simply ignoring the trend towards physical distancing, we would have expected them to continue going to places like supermarkets, liquor stores, and parks at the same rates as before. Instead, their visits dropped at almost the same rates as the very highest-income group,” says study lead author Jonathan Jay, assistant professor of community health sciences.

“This indicates that lower income people were just as aware and motivated as higher-income people to protect themselves from COVID-19, but simply couldn’t stay home as much because they needed to go to work,” he says.

Jay and colleagues used anonymized mobility data from smartphones in over 210,000 neighborhoods (census block groups) across the country, each neighborhood categorized by average income. They were able to see whether people from these neighborhoods stayed home, left home and appeared to be at work—staying at another location for at least three hours during typical working hours, or making multiple stops that looked like delivery work. The researchers also tracked movement to “points of interest”: beer, wine and liquor stores; carryout restaurants; convenience stores; hospitals; parks and playgrounds; places of worship; and supermarkets.

“The difference in physical distancing between low- and high-income neighborhoods during the lockdown was just staggering,” says study co-author Jacob Bor, assistant professor of global health and epidemiology.

“While people in high-income neighborhoods retreated to home offices, people in low-income neighborhoods had to continue to go to work—and their friends, family, and neighbors had to do the same,” he says. “Living in a low-income neighborhood is likely a key risk factor for COVID-19 infection.”

To analyze the role that policies played in these mobility patterns, the researcher used the COVID-19 US State Policy Database (CUSP), a project led by study co-author Julia Raifman, assistant professor of health law, policy & management.

They found that the huge drop in mobility early in March had little to do with state policy, following similar patterns in different states regardless of when their orders went into effect. When state policies did go into effect, they modestly decreased mobility further—but did nothing to close the gap between low- and high-income neighborhoods.

“The orders did not have the effect of making it easier for lower-income people to stay home,” Jay says. But they did stay home to the degree possible, visiting non-work non-home locations less—which counters a major narrative about how different groups of people have responded to COVID, Jay says. “Early in the pandemic, there was a lot of talk about ‘non-compliance,’ and it was rarely directed at the people with the most power and privilege,” he says.

“We found strong evidence of compliance among the people who are most economically marginalized, which because of structural racism disproportionately includes people of color. As the pandemic has played out, the evidence of poor safety practices at the very highest levels of power has become more clear.

“Still, it’s deeply troubling that throughout the pandemic, staying home has been a choice for some people and not for others.”

The researchers say that closures are an important tool for states and cities to prevent the spread of the coronavirus, but that they need to be accompanied by other policies that make it easier for frontline workers to protect themselves.

“That people living in low-income households are more likely to face exposure to COVID-19 at work increases the importance of complementary policies, such as mask requirements in indoor spaces, that protect essential workers from COVID-19,” Raifman says.

“One of the most important arguments for mask mandates is that they protect the folks who are in public spaces not because they want to be, but because showing up is how they make ends meet,” Jay says. He also points to “policies that make it easier to work from home, stay home sick, and not to take a risky new job just to put food on the table.”

However, Jay says, policies that make it easier to stay home only help if people have homes. As a wave of evictions and foreclosures sweeps the country, he says extending moratoriums and enacting other housing policies continue to be an important part of the picture.

The study’s other co-authors are: Elaine Nsoesie, assistant professor of global health; Sarah Lipson, assistant professor of health law, policy & management; David Jones, associate professor of health law, policy & management; and Dean Sandro Galea.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.