Employment and Health.

Before beginning today’s note, an acknowledgement of the horrible recent events in the UK. The Manchester bombing has shown us, once again, how hate can lead to terrible violence. Our thoughts are with the families of those affected. In the face of such heartbreaking tragedy, it is more important than ever, I think, for us to continue our pursuit of healthy populations, as we work to build a safer, less uncertain world.

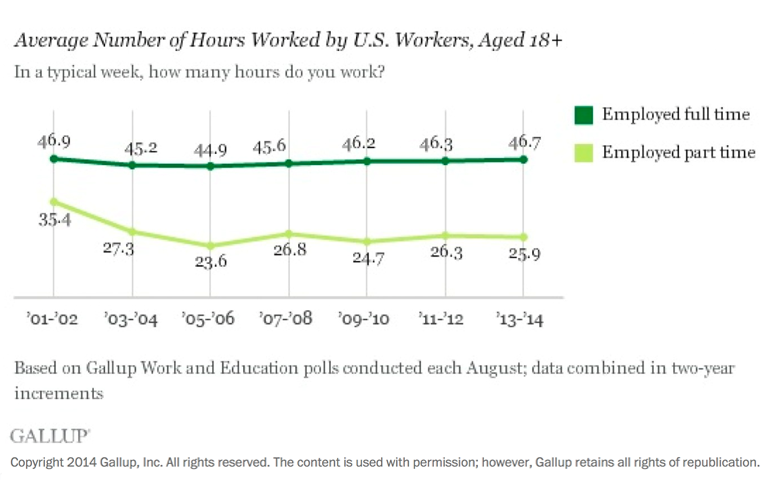

On to today’s note. Work is an important influence on our lives. Our work determines where we go every day, who we have regular contact with, the environment we are exposed to, even the number of hours we spend standing up or sitting down. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), Americans spend roughly 34 hours per week at work. These data, when deconstructed by industry, reveal that many US workers put in significantly more time than the national average. While 40 hours per week is widely considered the standard for weekly, full-time employment in the US, self-reported data suggest that Americans may work even longer than the average reported by the BLS. A 2014 Gallup poll placed the average work week at 46.7 hours for full-time and 25.9 hours for part-time employees (Figure 1).

Saad L. The “40-Hour” Workweek Is Actually Longer—by Seven Hours. Gallup Web site. http://www.gallup.com/poll/175286/hour-workweek-actually-longer-seven-hours.aspx Published August 29, 2014. Accessed July 29, 2016.

While collecting accurate employment data can be problematic—people sometimes cannot recall exactly how many extra hours they worked, leading to a risk of overestimation—it is clear that Americans spend a lot of time doing their jobs. A note, then, on the ways that work influences well-being, and some suggestions for how we can make sure that this influence is a positive one.

The connection between work and health has long been of interest. As thinking about employment—about both its function in society and its influence on the lives of workers—has evolved, it has over time motivated changes in what we expect of work, and the nature of our jobs themselves. In the 19th century, Charles Dickens wrote about his childhood work in a blacking factory, and the harm the work seems to have done to his mental health. In his novels, he would characterize the often brutal effects of industrialization on the working poor; his concern for the well-being of the laboring classes was also present in his nonfiction. In this sense, Dickens was a precursor to Upton Sinclair, who, in his 1906 book The Jungle, would capture the deplorable conditions of turn of the century meatpacking plants. The publication of The Jungle was a watershed moment in the Progressive Era, a period which produced important labor reforms; these measures were often prompted by a concern for occupational safety. In 1974, Studs Terkel’s book Working: People Talk About What They Do All Day and How They Feel About What They Do was released. It featured transcribed interviews with workers from a range of professions, reflecting on their lives and careers and the many ways the latter can shape the former.

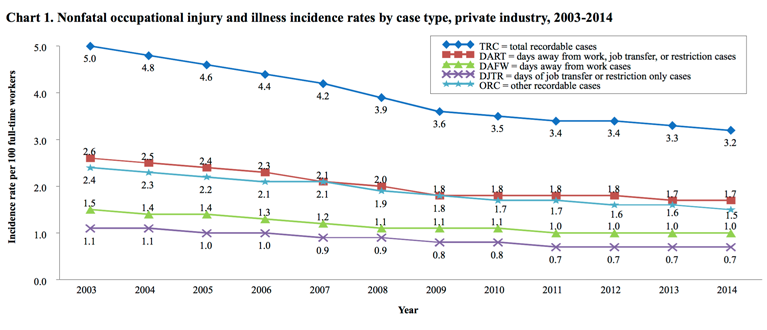

The physical effects of work can be substantial. The BLS 2014 Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries counted more than 4,500 occupational fatalities that year; 1,157 of these deaths were due to fatal roadway accidents, and 818 were due to falls, slips, and trips. Additional hazards included injuries by persons or animals, including workplace violence and suicide (749 deaths), contact with objects and equipment (708 deaths), fires (53 deaths), and explosions (84 deaths). The injury count was, perhaps expectedly, even greater. Although nonfatal occupational injury and illness rates have declined in recent years (Figure 2), there were almost 3 million nonfatal workplace injuries and illnesses reported in 2014, with an incidence rate of 3.2 cases per 100 equivalent full-time workers. The leading driver of occupational injuries or illnesses in the US in 2014 was “overexertion and bodily reaction” (384,260 cases). Another key hazard was falls, slips, or trips (316,650 days-away-from-work cases). The leading type of injury or illness was sprains, strains, or tears (420,870 days-away-from-work cases).

Employer-Reported Workplace Injuries and Illnesses—2014. Bureau of Labor Statistics US Department of Labor Web site. http://www.bls.gov/bls/newsrels.htm#OCWC Published October 29 2015. Accessed July 29, 2016.

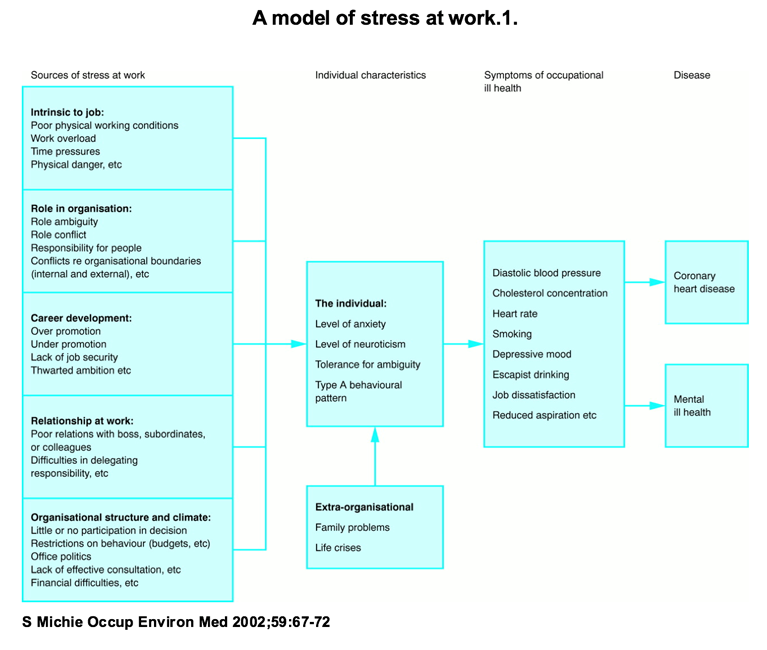

Work also has an influence on mental health. To borrow from the World Health Organization’s 2000 report, Mental Health and Work: Impact, Issues and Good Practices, “Although it is difficult to quantify the impact of work alone on personal identity, self-esteem, and social recognition, most mental health professionals agree that the workplace environment can have a significant impact on an individual’s mental well-being.” This is well illustrated by the problem of workplace stress and occupational burnout. Data suggest that the degree to which job stress produces health problems has much to do with a combination of the individual employee and the influence of environmental stressors—the workload, hours, lack of sleep, salary level, and interpersonal interactions that revolve around a given position (Figure 3).

S Michie. Causes and management of stress at work. Occupational & Environmental Medicine. 2002; 59: 67—72 doi: 10.1136/oem.59.1.67

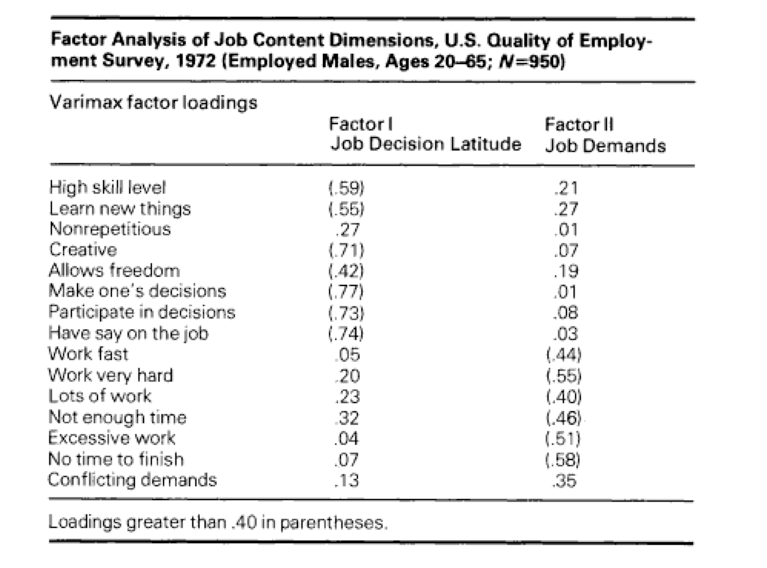

In 1979, Robert Karasek examined the phenomenon of worker stress. He wanted to know why an assembly-line worker and an executive could both have stressful jobs, yet the executive would report higher job satisfaction and greater overall mental health. The difference, Karasek found, was in the combination of two key job characteristics: job demands and job decision latitude. Job demands are simply the responsibilities of a position; the various projects we are tasked with completing to earn our pay. Job decision latitude is our degree of individual control over our work—how much creativity we are allowed to bring to bear, and the room for professional and personal development such latitude can entail (Figure 4). Karasek found that increased decision latitude meant a better overall work experience, even when job demands were high. High demand without high decision latitude had the opposite effect.

Karasek R. Job Demands, Job Decision Latitude, and Mental Strain: Implications for Job Redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1979; 24(2): 285—308.

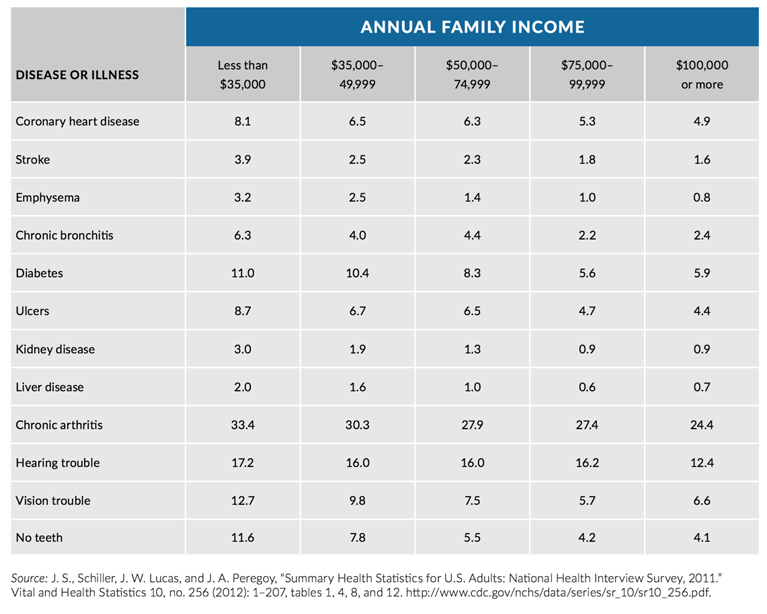

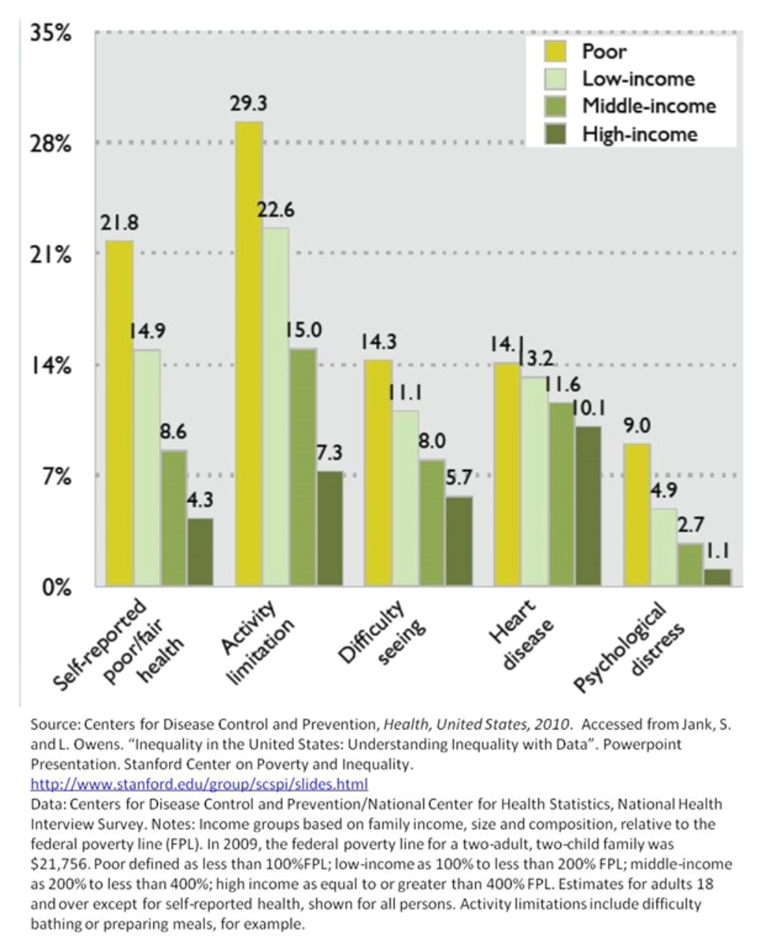

Coming back to one of the central drivers of health, work also influences health indirectly, through income. How much money we make shapes our vulnerability to a host of health conditions (Figure 5, Figure 6).

Woolf SH, et al. Prevalence of Diseases, by Income, 2011 (percent of adults). How Are Income And Wealth Related To Health And Longevity? http://www.urban.org/research/publication/how-are-income-and-wealth-linked-health-and-longevity Published April 2015. Accessed July 21, 2016.

The Brookings Institution Web site. http://www.brookings.edu/blogs/social-mobility-memos/posts/2013/10/02-healthcare-obamacare-social-mobility-venator-reeves Published October 2, 2013. Accessed July 29, 2016.

At the lower end of the income spectrum, in Scorecard on State Health System Performance for Low-Income Populations, 2013, The Commonwealth Fund found “wide state differences in health care for low-income populations are particularly pronounced in the areas of affordable access to care, preventive care, dental disease, prescription drug safety, potentially preventable hospitalization, and premature death.” Less tangibly, perhaps, employment shapes mental health through its connection with social status, or class. Social class can be difficult to define. The concept includes income, certainly; it also includes culture, background, and job type. Higher social status is generally associated with better health and higher life expectancy, while, conversely, lower social status can mean risk of higher morbidity and mortality from a range of diseases.

The connection between work and health has long been a focus of SPH; it is part of our scholarship. The work of Professor Les Boden has done much to advance knowledge in this area, as has the research of Professor Michael McClean. Both have worked to mitigate the hazards faced by workers, and to ensure that work environments are as healthy as they can be. Our academic and activist considerations, however, would be lacking if we were not also taking steps to make sure that our school is the kind of workplace where each member of our community can be happy and productive. We do this in three main ways. First, and most crucially, by making sure our school is physically safe. This priority is nonnegotiable, and one that we take great care to uphold every day, with an eye towards not only meeting safety standards, but exceeding them. Second, by creating a culture of faculty and staff that is based on mutual support and mentorship, where everyone is empowered to speak out if they feel overwhelmed or unsure about how to cope with their workload. Finally, with Karasek in mind, we seek to maximize decision latitude by encouraging creativity and fostering professional growth at all levels here at SPH, so that our work is informed not simply by professional obligation, but by passion.

I hope everyone has a terrific week. Until next week.

Warm regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Robert A. Knox Professor

Boston University School of Public Health

Twitter: @sandrogalea

Acknowledgement: I am grateful to Eric DelGizzo for his contribution to this Dean’s Note.

Previous Dean’s Notes are archived at: https://www.bu.edu/sph/tag/deans-note/