A Hate Crime Against LGBT Communities, With Weapons of War.

Last weekend, a gunman walked into a popular Florida gay club with an assault rifle and perpetrated the deadliest mass shooting in US history, killing 49 people and wounding more than 50. Following a hostage standoff, the gunman was killed in a shootout with police.

Last weekend, a gunman walked into a popular Florida gay club with an assault rifle and perpetrated the deadliest mass shooting in US history, killing 49 people and wounding more than 50. Following a hostage standoff, the gunman was killed in a shootout with police.

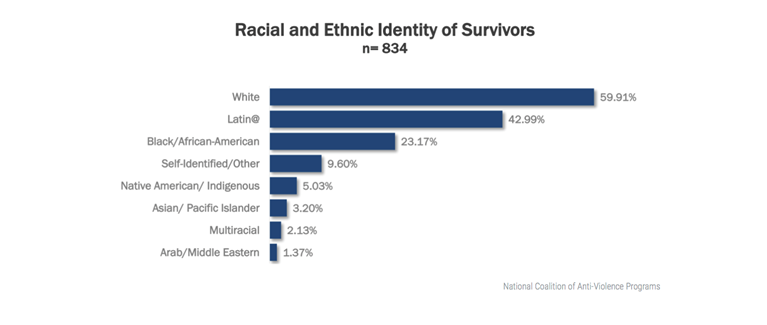

This crime, already horrible, is made more egregious for being a hate crime against minority populations, specifically the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) population, and populations of color. Almost all of the victims were people of color; it is well documented that LGBT people of color experience disproportionate levels of hate-inspired violence. Figure 1 demonstrates this disproportion. Generated by the National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs, it indicates that nearly 43 percent of anti-LGBT violence survivors are Latinx, and about 23 percent are black. What happened last week was not a random attack—it was targeted against a specific group of people, a group that, even in today’s more tolerant society, daily bears a disproportionate brunt of discrimination and hate.

“Racial and Ethnic Identity of Survivors.” 2014 Report on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, and HIV-Affected Hate Violence. Accessed June 15, 2016

Population health scholarship over the past two decades has illuminated how prejudice, discrimination, and segregation, along multiple axes, linked to interpersonal hatred and antagonism, have a pernicious and pervasive effect on the health of populations. Duncan and Hatzenbuehler, for example, linked LGBT youth suicide in Boston with neighborhood-level LGBT hate crimes involving assaults, and found that sexual minority high school students who lived in neighborhoods with higher rates of assault were significantly more likely to report suicide ideation or attempts. They also found evidence for a higher prevalence of marijuana use among these same LGBT students in higher hate crime neighborhoods, compared to their counterparts in neighborhoods with lower hate crimes. A meta-analysis found a two-fold excess in suicide attempts among LGBT individuals, a 1.5 times higher risk of anxiety and depression, and a 1.5 times higher risk of alcohol or substance dependence, which was even higher among lesbian and bisexual women. In the Nurses Health Study II, lesbian women were more likely to report depression and the use of antidepressants. A study of middle-aged adults revealed that gay and bisexual men experienced more panic attacks and depression than heterosexual men, and that lesbian/bisexual women had a higher prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder than heterosexual women.

Another study found that “structural stigma,” defined as anti-gay prejudice at the community level, was associated with higher all-cause mortality among sexual minorities. Professor Ilan Meyer put forward a conceptual framework that links stigma and prejudice to mental health disorders among LGBT people through hostile social environments.

Last weekend this hostility was expressed in the most violent way possible, enabled by a culture that prioritizes unfettered access to guns over the safety of its citizens. It is worth noting that many structural stigmas against LGBT populations—same-sex marriage resistance, anti-trans bathroom policy, protections for discrimination under the guise of “religious freedom,” bans on blood donation for men who have sex with men and trans women who have sex with men—are upheld by the same legislatures that enforce this country’s status quo on firearm access.

Guns enable hate. They give it a voice that it does not deserve to have, and should not have in our society. The massacre in Orlando underscored this point, and reminded us what we have long known: that these events happen with shocking regularity. Just this year, there have already been 133 verified mass shootings in the United States. More broadly, there have been close to 6,000 firearm-related deaths, more than 12,000 injuries, and more than 1,000 accidental shootings. In 2013, the US suffered more than 30,000 gun deaths—and there is no reason to think we will not see similarly horrific numbers by the end of this year. It would not be hyperbolic to say that, in the US, this type of event has become routine.

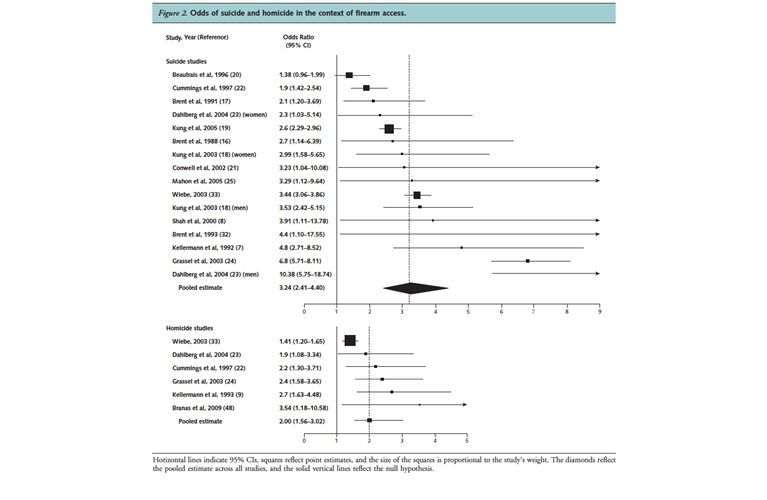

While arguments about the rights to gun ownership often center around self-protection from other firearms, the evidence is overwhelmingly clear that this argument is not supported by the data. Extant studies on the risks of firearm availability on firearm mortality have provided clear evidence of an increased risk of both homicide and suicide. A meta-analysis of 16 observational studies, conducted mostly in the US, estimated that firearm accessibility was associated with an odds ratio of 3.24 for suicide and 2.0 for homicide (see Figure 2), with women at particularly high risk of homicide victimization (odds ratio 2.84) compared to men (odds ratio 1.32). In the case of firearm suicide, adolescents appear to be at particularly high risk, relative to adults.

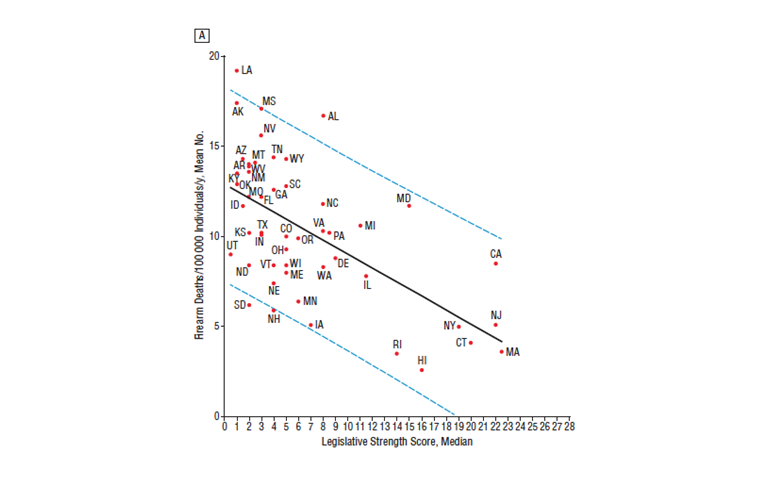

Another study examined the association between firearm legislation and US firearm deaths by state between 2007 and 2010, creating a “legislative strength score” based on five categories of legislative intent: curbing firearm trafficking, strengthening Brady background checks, improving child safety, banning military-style assault weapons, and restricting guns in public places. Higher legislative strength scores were associated with lower firearm mortality (see Figure 3), and adjusted multivariable models showed that compared to those in the lowest quartile of legislative strength scores, those in the highest quartile had a lower firearm suicide rate and a lower firearm homicide rate.

“Firearm Legislation and Firearm-Related Fatalities in the United States.” JAMA Internal Medicine. Accessed June 14, 2016.

Despite the clear evidence that guns pose a threat to health, the public health community has been unable to get traction as an effective voice on this issue. Unfortunately, instead of quality scholarship and policy efforts to map and respond to the risks of guns, we have seen the silencing of gun researchers, health practitioners, and policymakers intent on addressing these problems. Actions by Congress fueled by the National Rifle Association (NRA) in 1996 effectively defunded federal gun research, a still extant legacy. While translatable lessons from successful public health campaigns on smoking, unintentional poisonings, and car safety abound, the political will necessary to implement and test them with respect to guns has been absent.

What perhaps makes the events in Orlando even more egregious is the use there of a Sig Sauer MCX billed as “an innovative weapon system built around a battle-proven core.” This is a weapon of war that has no place in civilian society, no place even if one were to be in favor of broader access to guns, and no place if we ever want to move beyond the now familiar cycle of mass shooting after mass shooting. As Massachusetts Congressman and Iraq war veteran Seth Moulton has written, “There’s simply no reason for a civilian to own a military-style assault weapon. It’s no different than why we outlaw civilian ownership of rockets and landmines.”

What is the role of public health in this discussion? In many ways, I worry that the voice of academic public health has been far too quiet on this issue, simply because the typical mechanisms that support our scholarship—extramural funding chief among them—have not been conducive of this work. This suggests, then, that it falls to academic public health to organize itself in a way that will allow us to be a clear and compelling voice on the issue. It argues for an active role in translating scholarship, and a full engagement with the public conversation around this issue.

When we prioritize the proliferation of weapons of war over the safety of our communities, when we wink at hate and let it go unanswered, we signal our peace with the status quo. We say that we can live with the harm directed daily towards our neighbors and friends; that we accept the possibility that an angry, spiteful person could, at any time, access an assault rifle and use deadly force to broadcast his grievance to the world.

This issue of SPH This Week is a somber one. We do not include in it much of what we normally include. Instead we highlight our recent writing about the work that has emerged recently from SPH around the consequences of firearms and about the health of LGBTQ populations. This augments our “Enough” social media campaign during the week. It is our small part, necessary even if clearly not sufficient, towards making the acceptable unacceptable.

Until next week.

Warm regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Robert A. Knox Professor

Boston University School of Public Health

Twitter: @sandrogalea

Acknowledgement: I am grateful to Meaghan Agnew, Michelle Samuels, and Eric DelGizzo for their contributions to this Dean’s Note; I am grateful to many members of the SPH community whose dedication to these issues inspire this Dean’s Note and much of our work in this area. Particular thanks to our Activist Lab and our Communication teams who have led our “Enough” social media campaign. Parts of this Dean’s Note have appeared as previous Dean’s Notes, as well as in The Boston Globe.

Previous Dean’s Notes are archived at: https://www.bu.edu/sph/tag/deans-note/

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.