Jesus as Mother

Karen Jo Torjesen

1/28/1997

Bangor Theological Seminary Convocation- Pond Lectures

“Jesus as Mother: Crossroads Between Christology, Anthropology and Gender.”

This morning I didn’t think I woke up in the same state I went to sleep in (laughter.) It’s beautiful, I’m sorry you had to drive in it, but what a joy to see Maine in the winter as well as having seen Maine in the summer. Just for a few hours, I think I envy you your beautiful state. That was from a Californian (laughter.)

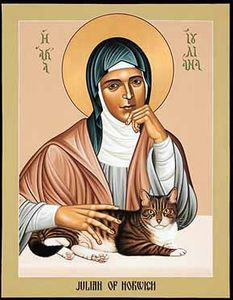

Introduction to Julian of Norwich

Today, a lot of time has passed since we talked yesterday. About 12 centuries, and we are now in the medieval world, and I am going to introduce you to, and I hope enchant you with Julian of Norwich. And you will probably gather easily from my presentation that I love her dearly, and always come back again and again to sit at her feet.

Today, a lot of time has passed since we talked yesterday. About 12 centuries, and we are now in the medieval world, and I am going to introduce you to, and I hope enchant you with Julian of Norwich. And you will probably gather easily from my presentation that I love her dearly, and always come back again and again to sit at her feet.

I began a serious exploration in the medieval period in the course that I call “Matristics: Medieval Women’s Theology,” And the reason for that is that my training is as a Patristic scholar. I am a scholar of the father’s of the Church. And as my feminist consciousness began growing, I began longing for the mothers as well. And by going to the medieval period, we do have the writings preserved of women theologians because during the medieval period, the prophetic ministry, that capacity to live along the boundaries of the human and the divine was highly valued. And so the women and the men who wrote out of that spiritual authority of their own immediate encounter with the divine, their works were gathered, treasured, copied, and honored. And so therefore from the medieval period, can bring you these writings. So what I was looking for in this course, is women’s contributions to theology, to the formation of Christian understandings of self-hood, Christian ways of thinking about the divine, and a distinctive way of life.

So I came back to those questions, what it means to be human, theological anthropology and specifically asking: how do women’s understandings of what it means to be human enlarge theological anthropology? And then asking again: how do women understand the relationship between the human and the divine? What is their understanding of God, their doctrine of God? And how again do they understand- women who are interpreting Christian experience- how do they understand soteriology, how do they explain sin, and then consequently what the processes of redemption are? As I said yesterday, I’m interested in women theologizing in communities, in communities of women, in communities of women and men. This theologizing, when I highlight an individual theologian, I still understand it to be the work of a community. And the expression given to it by an individual, is nurtured entirely by the matrix of the community in which she or he does their theological writing. I would even argue that Augustine’s theology is theology of a community. And it shifts as his community shifts, from his early years when he was a doctoral student when he hung out with fellow students, had a small group of friends, in a kind of peripatetic retirement community later of African bishops, and then a canonical community, each time his theology reflects that rootedness in the community. Well, I was asking initially when I did the course in matristics, is there a woman’s theology? And you keep wondering if there is something that can be identified distinctly as woman’s contribution to the historical theological tradition. But when I did this course, and we read about 15 different medieval women, I discovered that there was not English rose garden with orderly rows of blooming bushes with the colorful variety of familiar blossoms. But instead, women’s theological writing, like men’s theological writing, is a wild tropical garden, dense, overgrown, with astonishing species, strange and beautiful. But there is no single woman theological voice, probably because there is no Woman (with a capital W)- a hypostasized, generic femininity and ontological femaleness. There are women. Mediterranean fullers and dyers, weavers and tent makers, landholders, and merchants, they are medieval educated anchorites, wealthy Swedish noblewomen, women weavers, there are beguines, there are women as well as men, who are grounded in really distinct historical experience. And so instead of an essential woman’s nature in which female identity is fixed, there is a diversity of women subjectivities, experiences of the self formed by the experience of female embodiment, menstruation, pregnancy, birth, nursing, menopause. And by the forms of embodiment that men and women share together, being born, being nurtured, maturing, aging, work. Subjectivities or selfhoods formed by tasks set by gender and class. Subjectivities formed by languages, norms, customs, ethnicities of people, ethnicities of city, ethnicities of race, and eventually as we move the modern period, identities of nationality. And what Julian will afford us, and the medieval world will afford us, is a wonderful counterpoint to the world of early Christianity, is the opportunity to really engage embodiment- what it means to be in a body, and theology that arises directly out of the experiences of the body. This is the distinctive contribution of the medieval world I think, to makes us aware in that way.

Julian’s Christology

Now, let me begin the presentation of Jesus as Mother, as Julian develops this distinctive Christology. Which I should say, I’m picking Julian as the representative, Jesus as Mother as a Christology, we find really throughout the range of monastics, male and female. Careful study by medieval scholars shows there’s differences in the way that male monastics use Jesus as Mother as a Christology, and the way that the women do. This is what Julian writes:

“As God is our father, so truly is God our mother. Our father wills, our mother works, our good Lord the Holy Spirit confirms, and therefore it is our part to love our God in whom we have our being, reverently thanking and praising him for our creation, mightily praying to our mother for mercy and pity, and to our Lord the Holy Spirit for help and grace. And so Jesus is our true mother in nature, by our first creation, and he is our true mother in grace by his taking our created nature. All the lovely works, and all the sweet loving offices of beloved motherhood are appropriated to the second person, for in him, we have this godly will, whole and safe forever, both in nurture and in grace, from his own goodness, proper to him.”

I understand three ways of contemplating motherhood in God.

1. The first is the foundation of our nature’s creation. Creation from God, creation as Soul.

2. The second is his taking of our nature, where the motherhood of grace begins, referring to the incarnation.

3. The third is motherhood at work, and in that, by the same grace everything is penetrated in length and in breadth, in depth and in height without end, and it is one love, the working of the holy spirit.

That’s the motherhood at work. And then we’ll explore in Julian’s thought what she means by each one of these.

Now, when I spoke yesterday about what it means to take as our companions for this quest for the historical Jesus, sisters and brothers from another historical period, or from a different culture, it means becoming acquainted with them, starting to know them in their particularity, in their distinctiveness, and in their otherness, and in their strangeness. And it’s that strangeness and otherness that I want to begin. And I thought the way that I would best honor Julian is to let her make that first presentation of herself, for her to tell you who she is. And then, we’ll come back and explore what that means.

She begins as an introduction to her book, which she calls The Revelations of Divine Love or Showings,

“Here is a vision shown by the goodness of God to a devout woman and her name is Julian, who was a recluse at Norwich, and still alive AD 1413, in which vision, there are very many words of comfort, greatly moving all those who desire to be Christ lovers. I desired three graces by the gift of God. The first was to have recollection of Christ’s passion. The second was a bodily sickness. And the third was the have God’s gift of three wounds.”

We want to ask what does she mean by recollection? She’ll refer to bodily sight, and bodily pains, and compassion. And these will all focus on Christ’s passion on the figure on the image of the crucified Christ. Her second prayer, is for the gift of a bodily sickness. When she was 30 and a ½ years old, God sent her the bodily sickness for which she had prayed. For three days and for three nights, she was terminally ill and expected to die, and had sent for the priest to administer last rites. She said,

“For it seemed to me that all the time that I had lived on earth was very little and short in comparison with the bliss, which is everlasting. So I thought ‘good Lord, is it no longer to your glory that I am alive?’ And my reason and my sufferings told me that I should die. And I felt that the upper part of my body were beginning to die- my hands fell down on either side, I was so weak that my head lulled to one side. The greatest pain that I felt was my shortness of breath, and the ebbing of my life. Then I truly believed that I was at the point of death. And suddenly in that moment, all my pain left me. I was as sound particularly in the upper part of my body as I ever was before or have ever been since. I was astonished by this change. For it seemed to me that it was by God’s secret doing, and not natural.”

She prayed for a terminal illness. It’s a gift of grace. That’s strange enough (laughter.) And then, the gift was granted, and she received the terminal illness- actually she writes, she was so endearing, that she actually forgot that part of her earlier prayer (laughter), and it only came back to her when she fell deathly ill that she had in fact prayed for this illness. But we must also consider the third thing that she prayed for. She prayed for three wounds. Notice again, the metaphor of suffering and of illness. She’s prayed for the sickness, and now she’s prayed for three wounds. And she names them the wounds of contrition, the wound of compassion, and the wound of longing. And this of course reflects back to the three wounds on the body of the crucified Christ.

So, questions we have then as we first meet Julian, is why bodily suffering? Why sickenss? Why pain? Why painful death? Why bodily sight? Why the focus on the crucifixion? And what is this repeating theme of compassion rooted in this constellation of suffering, illness, and body? And I’d like to answer these questions about Julian by stepping back a bit and introducing something of the spirituality of the medieval period. And to do that, I’m going to go to very familiar figure, Francis of Assisi, to begin setting the context for Julian prayers for terminal illness.

Introduction to Francis of Assisi

Now you remember Francis, I’m sure as the model for the apostolic life. And what he chose for himself, and then made the foundation for his order, was a life in the imitation of Christ. Now, that sounds simple, we all want to imitate Christ, that’s been a theme throughout the history of Christianity. What becomes intriguing is, what the imitation of Christ meant now in the 12th century, with the rise of capitalism, with the transition from feudal society to urban mercantile society, production in the cities, growth of wealth, the beginning of the national monarchies. In this transition, the spirituality of that period focused on poverty. And the understanding was, in adopting the apostolic life, that to follow Christ, is to know the historical Jesus. And the way that we really know the historical Jesus is through having his experience. It’s bodily knowledge. To really understand, to really enter into the experience of the historical Jesus, means to know what it felt like to be in his body, which means that my body, that our bodies can be the medium, the place at which we can encounter the historical Jesus through experiencing what he experienced. And this is the focus of the apostolic life. And to experience what Jesus experienced as Francis understood it, and as many of the medieval Christians did, was to adopt a lifestyle that imitated the lifestyle of Jesus- homelessness, wandering, preaching, poverty, begging, suffering. And so, Francis institutionalized this imitation of Christ in the body as a rule for his order. And all of those monks who became part of his order then refused to own any property- no personal property, let alone no real property- adopted the lifestyle of begging, which meant not only poverty, but also humility, or humiliation (knocking) on the door of a peasant household, smelling, scraggly beggar outside, extends the bowl, makes a request, the irritated housewife, grabs the dishwater, and there you have it. The role of beggar meant to identify with the lowest class of society, with the lepers, the outcasts. To take up their social identity, as well as just being poor and without. And the importance for Francis was that kind of bodily solidarity with the poor was the bodily solidarity with the historical Jesus. And it was through this bodily solidarity then, that he believed he could come to know Jesus. This was the way of entering into the love, the compassion of the quest for the historical Jesus.

Francis also prayed for the final intensification of that bodily experience of the sufferings of Christ. And he prayed for the wounds. He prayed that he might have the gift of the wounds to enter finally into, and most fully, into the experience of the suffering of Christ. And late in his life, praying on Mt. Alverna, in a cave as he was wont to do, retreat to prayer. He had a vision of a Seraph, and he received in his hands, and in his feet, and in his side the wounds in his body, the wounds of Christ. The stigmata. The meaning of the stigmata for the monks who quested for this experience was not the signature on the body that identified wholeness, their quest was for suffering that would bring them into that experience, that solidarity with Christ.

And so it’s within that context of spirituality that Julian prays for the terminal illness because it is the gift of suffering, puts her then in the experience of the suffering of the historical Christ, and that is the only way to measure, to grasp to experience the love. And the connection that you’ll see Julian making always is between the suffering and the love. That’s the theme of compassion. It is by having that experience of pain, that experience of suffering, that is what measures the depth of the love, and is the source of the compassion.

So let’s return now to Julian. And let me just sketch really briefly the world of 14th and 15th century Norwich. Norwich, second largest city next to London in England. The center of town has the castle. Way along the perimeters are the city walls with their gates. The cathedral dominates a large part of the area of the town. There are 56 churches through Norwich, and there are 35 anchorages. Julian is one of these 35 anchorite hermits. Julian was an enclosed hermit. That is, that she lived her life in enclosure in a small room that adjoined the church of Norwich where she spent her entire life. Commodious room, an altar, a window, a bed, and a place for prayer. A window into the church where she could then, from her room, participate in the masses that were said in the church. But she spent her life not in a monastic community, but as a hermit, enclosed adjoining the church. She was also sought out as a spiritual counselor there.  We know very, very little about Julian, but we do know that she was educated. She wrote her visions herself. She did not need a scribe. It means first of all that she knew Latin. She was educated, could read and write in Latin. She read the Bible in the vulgate. She made her own translations. From her writing, she seems to be fairly widely read in the theology of her day. Her language shows that she studied rhetoric, which reflected in the quality of her writing. And she’s also at that transition, she is one of the first writers to write in English. So she’s the mother of our language, as well as the mother of our spirituality in many ways. Her decision to write in English and that was beginning to happen, and that is very important, and just as it was in a few decades important Luther’s decision to write in German instead of Latin. This means the transition from theological knowledge, and theological authority shifting from the church and the clergy, to the laity- that shift in language- and that Julian wrote in English is important for that transition. She was also part in her spirituality of the daily readings, the lexio divina, which is part of the canonical hours. And I think this will provide a helpful context for the way that her visions have been received, how she received them and what she did with them.

We know very, very little about Julian, but we do know that she was educated. She wrote her visions herself. She did not need a scribe. It means first of all that she knew Latin. She was educated, could read and write in Latin. She read the Bible in the vulgate. She made her own translations. From her writing, she seems to be fairly widely read in the theology of her day. Her language shows that she studied rhetoric, which reflected in the quality of her writing. And she’s also at that transition, she is one of the first writers to write in English. So she’s the mother of our language, as well as the mother of our spirituality in many ways. Her decision to write in English and that was beginning to happen, and that is very important, and just as it was in a few decades important Luther’s decision to write in German instead of Latin. This means the transition from theological knowledge, and theological authority shifting from the church and the clergy, to the laity- that shift in language- and that Julian wrote in English is important for that transition. She was also part in her spirituality of the daily readings, the lexio divina, which is part of the canonical hours. And I think this will provide a helpful context for the way that her visions have been received, how she received them and what she did with them.

First of all there was the reading aloud that was active and affective. Then there was a period of meditation in which what was read is secured in the memory by again calling on the emotions, using the imagination, seeing, hearing, feeling, whatever was required to make vivid the reading and secure it in the memory. Then that moved to a phase of prayer, of petition, and desire for God. And that desire you’ll hear repeated again and again in Julian. And then finally contemplation, which is the fruits of that desire coming through the power of imagination, through art, through the visual. And Julian’s visions are right at that transition, at the point of death when she’s returned to life, she is gazing on the crucifix, which is presented to her as part of the last rites, and that vision of the crucifix suddenly becomes alive for her. And she watches the body on the crucifix change as it moves through death, and begins to experience affectively and emotively what that means.

And so she has, in this very short period of time, 14 visions. And six of them are focused on the passion, on the crucifixion. And she writes her visions down, and the others are on spiritual teachings. She then reflects, she reads, this becomes like a sacred text, she reads, meditates on these visions for the next 30 years. And then writes again, expanding them, commenting on them, and elaborating them. And that’s what we have in the book of Showings.

Julian’s Theology

Now what I want to do is to unpack Julian’s theology. And I think my favorite way to introduce Julian is with a simple line where she says,

“And God rejoices that he is our father, and God rejoices that he is our mother. And God rejoices that he is our savior. And Christ rejoices that he is our spouse.”

And these are the five high joys. What’s so distinctive about Julian here, is that she is not talking about our joy in God, or that pleasure that we have in God.

She is talking about God’s pleasure in us.

About God’s delight in us.

About the joy that we bring to God.

About how we bless God.

How much fun we are for God (laughter.)

You see, as we move into this kind of language, this is different. So we’ll explore more what she means by the motherhood of Jesus.

“Jesus is our mother in nature, and our mother in grace, because he wanted altogether to become our mother in all things, made the foundation of his work most humbly and most mildly in the mother’s womb, and he revealed that in the first revelation.”

And she’s talking about the first revelation that she saw of Mary. “Our mother in nature,” she talks about it also as “our mother in kind is the substantial unity of what we have with God.” And what she means by that is that as we talked about the divine wisdom, Sophia, being present at creation, and being through whom creation flows, what Julian does, is she makes that a maternal image. That is, of all creation flowing from Christ as mother, that is that work of cosmic creation. That is a work of motherhood. That is a mothering role. And why she uses the mothering metaphor is because understanding that role in creation, that role of Jesus in creation means that through the mothering metaphor is that the bonds between what is created and the creator are the bonds of motherhood. And the language that she uses continually for the divine relationship is the language of bonding. What we would in psychology call bonding.

Knitting and wanting are the ways that she said it in 14th century English. So Jesus is our mother in kind, mother of our substance, and is the mother of mercy, is the mother of our sensuality. And this is the word that she uses for embodiment, for the incarnation, for our embodiment is our sensuality. And Jesus gave birth to us in our sensuality, joined to us in our sensuality in the incarnation. So, that creative work of our embodiment comes from our mother Jesus who bore us in our embodied state, our mother Jesus who also has given us our life through the original creation, the life of our souls. The motherhood of Jesus is her metaphor because in speaking of this theological work of creation and incarnation, the mother service is nearest, readiest and surest. Nearest because it is most natural. Readiest because it is most loving, and surest because it is truest. No one ever might, or ever could perform this office fully, except only him.

“We know that all our mothers bear us for pain and death. O, what is that but our true mother Jesus. He alone bears us for joy and for endless life. Blessed may he be. So he carries us within him in travail and love until the full time when he wanted to suffer the sharpest thorns and the cruel pains that ever were and will be, and at the last he died. And when he had finished, and born us for his bliss, still all this could not satisfy his wonderful love. He revealed this in his words of great surpassing love ‘if I could suffer more, I would suffer more.’ But he could not die anymore, but he did not want to seek working. Therefore, he must need nourish us for the precious love of motherhood has made him our debtor.”

Let me unpack that a little bit. Julian says Jesus is our mother. Our own mothers gave us birth, and they gave us birth into a life of pain, and eventual death. But our mother Jesus gave us birth into a life that is endless without death, and into a life of bliss. And then she says, now watch what happens, she talks about the birth pains of mother Jesus, travailing, going into labor, the labor intensifies, the pain intensifies, reaching an ever and ever higher threshold. Now what she does is she superimposes them on the crucifix. Crucifixion, the suffering of the crucifixion are the labor pains of our mother Jesus as he travails, and suffers, and anguishes, and does it in order to give us birth. And we are birthed through that suffering on the cross, and we are birthed to endless life. And the joy of Jesus our mother giving us birth is so great that the labor pains of the crucifixion are nothing to the joy of having birthed us. In fact, if greater sufferings were required to have birthed us, he would have gladly suffered the more. And Jesus is our mother through this labor on the cross in such a way that that bonding has taken place. And that we are forever loved, and forever nurtured through that connectedness that only birth gives. And that’s the source of our security, of our confidence, and sense of shelter. And the love of Jesus our mother is that we were birthed through her body.

Now, Julian carries this theme of the motherhood of Jesus, and she says,

“The mother can give the child to suck of her milk, but our precious mother Jesus can feed us with himself, and does most courteously, and most tenderly with the blessed sacrament, which is the precious food of true life. And with all the sacraments, he sustains us most mercifully and graciously, as he meant in these blessed words.”

So the ministries of the Church are that nurture that comes from the breast of the mother Jesus. I think my favorite part of Julian’s image of Jesus as mother, is her understanding of sin. And I might need to translate this for you, but let’s see, “But often when our falling and our wretchedness are shown to us, we are so much afraid and so greatly ashamed of ourselves, that we scarcely know where we can put ourselves.” This is a scared child. “But then our courteous mother does not wish us to flee away. For nothing would be more pleasing to him, for he then wants us to behave like a child. When it is distressed and frightened, it runs quickly to its mother and if it can do no more, it calls to the mother for help with all its might. So he wants us to act like a meek child saying, ‘my kind mother, my gracious mother, my beloved mother have mercy on me. I have made myself filthy and unlike you. And I may not, and can not make it right except with your help and grace.’” Julian’s vision of sin is dirty diapers (laughter.) It’s not a big deal. Just come, and mother Jesus will fix it. Now there, now there, don’t you feel nice that you’re all clean and dry? Sin is not a great crisis for mother Jesus, because she can take care of it, so we should not be afraid of our sinfulness and go running.

“When I first saw that God does everything which is done, I did not see sin. And then I saw that all was well. But when God did show me sin, it was then that he said ‘all will be well.’”

Julian gives to us, I think, an image of Jesus as mother that connects us profoundly with the experience of embodiment, with being embodied and makes of that experience, of being in bodies, the central source for our understanding of the depth of the love and the connectedness and the potency of that bond between God and us that has taken place in a twofold way from creation and from redemption. She has drawn much of her understanding from medieval spirituality, from the imitation of Christ, and that equation between suffering, and love, and compassion: suffering as the measure for compassion, and as the source for it. And that’s the legacy of the historical Jesus that we can draw from the medieval period, that in some ways can get us closer to the first century than even the second century Christians did with their proximity.

MODERATOR: Thank you very much. We have about ten minutes for questions. We started a little late. I just wanted to say, the first time I ran into Julian was 1982 or 83 and it was wonderful to go back and visit her this morning. Jim?

JIM: I was wondering did she actually disagree with Augustine’s original sin, and how did she address that? Did she actually address it or not? I’m really curious.

KAREN JO TORJESEN: She works out- let me step back a little bit. Augustine’s doctrine of original sin is a struggle to address the whole question of the human condition, so it’s one distinctive theological interpretation of it. And it’s late, it’s fifth century. So we don’t have that understanding of sin earlier than Augustine. Nor does it develop at all in Greek Christianity. Now, Julian was very aware of those doctrines, and so she’s working as a way of trying to understand how to integrate her clear vision of the work of Christ with those doctrines. And where she comes out is her vision of love swallows up the dilemma of original sin. In other words, it eclipses it. The love is so potent, the bonding so intense that the original sin can be there, that its potency is much, much weakened. She is very much a faithful daughter of the Church. She existed during the period of the inquisition, so she existed during the period of the inquisition meaning theological care has consequences (laughter.) And, her teachings were never challenged by the Church. Her orthodoxy was never challenged. And so one of the things that’s wonderful about Julian is to have a woman theologian who is in a way pushing the boundaries so much, who still is in complete harmony with the Church. Now what she does continually in her revelations is she reaffirms her loyalty to the Church and the teachings of the Church. She clearly positions herself fully under the authority of the teachers of the Church. At the same time, she subverts it by, she has this independent authority that comes from her revelations, which medieval spirituality granted- this independent authority, this direct revelation that she appeals to. But she always appeals it is by saying ‘that poor ignorant woman that I am.’ And then she goes on to say, ‘well, I shouldn’t really be teaching, of course I’m not a teacher because I’m not a male. But it is so important that everyone understand this revelation that’s clearly for more than me, so perhaps I’ll just write it. And then share it as widely as I can, but it wouldn’t be teaching.’ (laughter.)

QUESTION: Julian works really hard to cultivate this relationship with God through all this love and suffering and everything. And yesterday you talked about this fellow who thought that by the virtue of baptism, we all have access to divine wisdom. Well, was this hard work too, or it just kind of happens if you’re there?

KAREN JO TORJESEN: Well, yeah, I’m not sure. Julian’s suffering was like four days. And she’d actually forgotten that she’d prayed for this terminal illness. So the language of her revelations is of joy and delight, and of discovery and profound connectedness and relatedness. It doesn’t breath at all with that sense of labor, or burden or suffering. I don’t think that’s how she would describe her work, or the work of theologizing.

QUESTION (difficult to hear): If sin was not a big deal, why is it that Julian has a radical renunciation of life by embracing poverty? She seemed to radically renounce the life that was around her and be a radically different Christian when she comes to. And it seems to me that they would see that as the life that was around them and she would be kind of cynical and react against it, and yet she doesn’t see it as a big deal.

KAREN JO TORJESEN: There’s, well, some of the monastic traditions really focused on penitence as the basis for the monastic life- so fasting, vigils, reading the penitential psalms were all disciplines focused specifically on sinfulness and on eradicating it. I mean, that’s where Luther comes from. He comes from that Augustinian monastic tradition. The kind of, and Francis is this way too. Francis talks a lot about joy, and the penitential dimension is simply not present in Francis’ work either as in Julian’s. And the renunciation of the world, is not, in the way in which these individuals see it in their traditions, the renunciation of the world is not because the world is wicked or evil, it is that it just gets in the way. It’s superfluous. It’s unnecessary. I mean, there’s a whole variety of spiritualities around renunciations, so these only represent two.

QUESTION: God has a lot of anger in the Bible. Does she really not refer to God in this way at all?

KAREN JO TORJESEN: It’s interesting. She’s clearly, her whole tradition. I was thinking about the way Professor Wright was working with the whole teachings, tradition of Jesus that were quote ‘apocalyptic,’ it was really to say, it was a counter polemic against the idea of revolt. So his whole message was a message directed against the theme of revolt, and advocating peaceful, non-violent resistance. Well Julian’s does not address God’s anger directly in that sense, but her entire revelation is directed toward the view that God is angry. In other words, her whole treatise addresses God’s anger. In a society that is primarily seeing God as angry, and interpreting their lives as God’s judgment, so it’s a major polemic against the prevailing view. That’s how I would see her work, that that really is her major intent, to undermine that worldview.

QUESTION: (not all decipherable.) Jesus, despite the fact that medieval Christianity…how would you compare modern Jesus with modern Mary? (?)

KAREN JO TORJESEN: It’s very interesting because for Julian, Mary is the second most important figure. And there’s a real parallel there. Because in her opening, not only does she want to know the sufferings of Jesus, but she wants to know what it feels like to be Mary, to be Mary at the foot of the cross. To know Mary’s suffering as she watches her son die, and that her entry into Mary’s suffering is her entry into Mary’s love. And by entering into Mary’s love, then that gives her access to enter into the love of mother Jesus. So Mary’s a real bridge to the maternal Jesus.

QUESTION: Hi. This totality of body, I wanted to go back and ask, was Julian reflective about who supported and cared for her body? I mean, I think her energy says…She was a recluse, who was cleaning up for her? Does she ever give any thought to the communities that supported her?

KAREN JO TORJESEN: There’s of course, with Julian, all we have is her visions, and her elaborations of her visions. I mean, we have just nothing about her life, who she was. I mean, hardly any biographical data at all. So we really don’t even have any way of answering that question. Now, I think it’ a really interesting question, because of course there’s a class question here that probably, if you think of Julian’s education, it’s likely then that she comes from a propertied class and had those who served her as well. And in the language, in the way that she uses the courtly imagery too, there’s a kind of world that she seems to move in an feel very comfortable in with that kind of imagery. I have a student who did a really absolutely fascinating paper on Julian, and if I’d thought of it, I would’ve gotten permission to use it from her. But the black plague swept through southern England three times during Julian’s lifetime. And as you know, three days from healthy to rotting corpse with the black plague. And she, this student, has interpreted Julian’s theology as a form of pastoral counseling, as a way of helping people deal with the loss of death, as a way to find joy in the face of death. And she wanted to make Julian really a central guide to pastoral counseling in the context of AIDS. And that medical setting for Julian I think would be very very fruitful.

QUESTION: I’m struck by her prayer for the three wounds. And the first one was contrition. And what did she mean by that?

KAREN JO TORJESEN: It’s really interesting- I keep saying that don’t I? I’ll have to get a better lead in. Contrition is a central part of medieval spirituality. And in its normal context is an awareness of sinfulness. What sinfulness turns out to be in Julian, and especially around contrition, is incominteretness (?). Meaning, that the ontological distance between us and God is so great, not that I’m so wicked, but that I’m so little. And it goes back to the notion of that child, you know the baby sense of incominteretness with the adult.

MODERATOR: I thank you very much.

(APPLAUSE)