Living Inside the White Box: Dweller-arranged Interiors in the Earliest Modern Mass-housing Developments

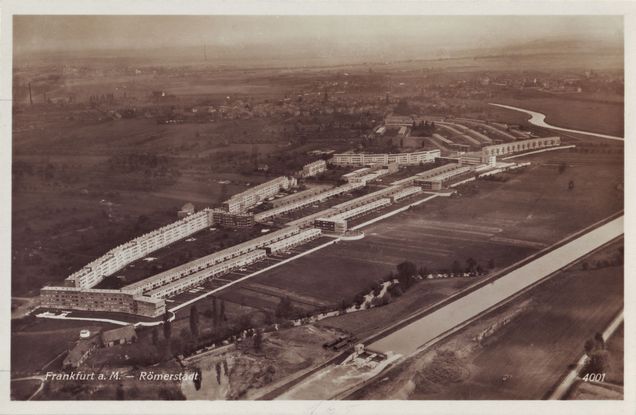

Known collectively by the name of their lead planner and architect, the eighteen Ernst-May-Settlements are residential developments containing almost 15,000 houses and apartments around Frankfurt, Germany (fig. 1). Constructed mainly between 1925 and 1930, they were a response by the recently-elected socialist government of the city to a housing crisis triggered by rapid population growth due to urbanisation, wartime industrialisation and the neglect of the housing stock during and after World War I. Being amongst the first modern mass-housing developments, they moved beyond the individual projects by collaborative groups such as Bauhaus into the practical business of providing decent-quality homes for the poorly housed working people of Frankfurt. May led a team of architects working for the city who were responsible for the process from town planning and domestic and public building design and construction through to the smallest details of fixtures and fittings and furniture design.[1]

These settlements are unique in the history of domestic interiors. For the first time, residents in a modern mass-housing environment had access to modern furniture; serially produced, designed with the size, layout and style of the houses in mind and made available at affordable prices by using the financial power of the city government (fig. 2).

For art and architectural historians, the starting point for the analysis of domestic interiors has been an examination of images supplemented by a connoisseurial examination of objects considered significant by the researcher. This approach has inevitably led to a focus on noble and wealthy households, whose interiors have been recorded in paintings and from which there are extant inventories and valuable objects. Only in the last quarter of the twentieth century did sociologists and anthropologists move beyond this class barrier to examine the links between identity and domestic interiors in mass-housing contexts.

There has still not been a scholarly examination, however, of the intersection of the earliest developments, modernist design, and mass-housing; and the literature produced so far has focused on external design rather than the interiors. Initially, I sought to close this gap by interviewing families who had lived for many years in these early mass-housing settlements. I hoped to find photographs of family celebrations or special occasions for which the background would be as significant to my research as the individuals themselves. Locating long-term residents was not simple, but by attending residents’ association meetings, forum discussions, and exhibitions, I gradually built up a network of contacts. This group directed me to their friends, relations, and neighbors, who were early occupants of the developments. With a list of about fifteen, I felt confident that there were enough to go ahead with the project on this basis.

To date, I have interviewed ten residents, ranging from those in their nineties who have spent their whole lives in the settlements to others who remember their parents’ or grandparents’ houses. My work has been helped by the existence of a substantial group of residents whose families have remained in the same house for three or more generations, fostered by a strong sense of community and the introduction of inheritable tenancy rights after World War II.

While these interviewees have indeed provided me with some photographs, I was able to tap into a much richer seam of information about family connections to the location and about the provenance of objects still in their possession. Our discussions usually open with a description of the house in which they grew up–which is sometimes still their home–and how the space used to be furnished, as they remember it.

Residents also reveal attitudes and approaches to the interior arrangements of the interwar period, suggesting a broad spectrum of ways in which furnishings were acquired, inherited, crafted, re-worked and disposed of. An example can be found in the frequent references to furniture which had been hand-crafted by the interviewee’s fathers or grandfathers. As some of these makers were not trained carpenters, this indicates a longer tail of the tradition of handiwork found amongst the families of manual labourers than might be supposed in a modern, urban environment. Conversely, there has been little to suggest that boundless consumption, an issue which has been at the heart of the discourse on domestic interiors since the middle of the twentieth century, had an antecedent in these settlements.

The accounts of the residents have also drawn out a particular characteristic of domestic interiors which is central to their accounts of lived-in interiors; that they are in a constant state of flux but also offer a historical continuity between present and past generations. My revised research approach now draws on oral history methodologies, as a means of collecting information and to provide a critical framework to deal with issues such as the unreliability of memory and the extent to which interviewees can ever be objective observers in their own homes.

The domestic interiors of interwar mass-housing may seem to have passed into collective, rather than individual, memory. However, my work reveals that we are just on the cusp of that change and still have an opportunity to capture valuable art and architectural historical data, provided we are ready to act now and to employ a wider range of research and interpretative methods than have been adopted in the past.

Stephen Kerr

____________________

[1] For those interested in these lesser-known settlements in Frankfurt, I recommend reading Susan R. Henderson’s Building Culture: Ernst May and the New Frankfurt Initiative, 1926-1931 (2013) and viewing the settlements, as they were and as they are now, on the website of the Ernst-May-Gesellschaft, www.ernst-may-gesellschaft.de.