26

PARTISAN REVIEW

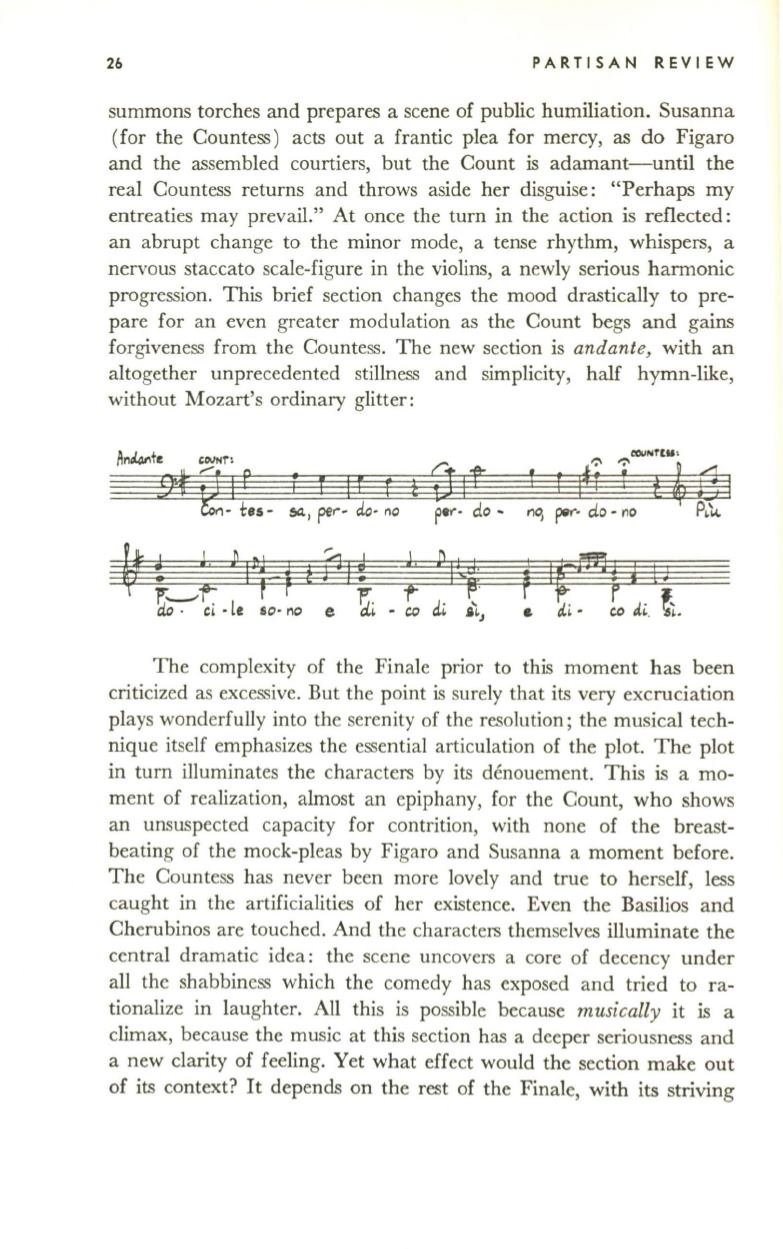

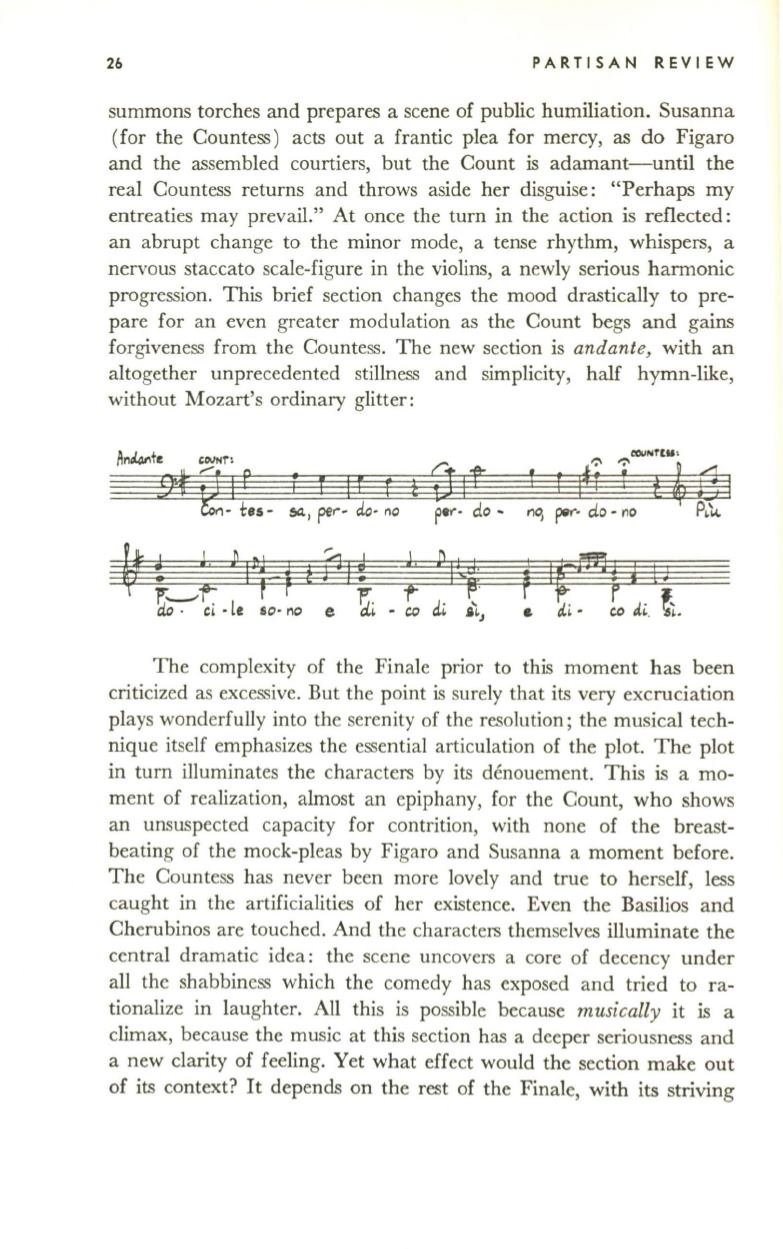

summons torches and prepares a scene of public humiliation. Susanna

(for the Countess) acts out a frantic plea for mercy, as do Figaro

and the assembled courtiers, but the Count is adamant-until the

real Countess returns and throws aside her disguise: "Perhaps my

entreaties may prevail." At once the tum in the action is reflected:

an abrupt change to the minor mode, a tense rhythm, whispers, a

nervous staccato scale-figure in the violins, a newly serious harmonic

progression. This brief section changes the mood drastically to pre–

pare for an even greater modulation as the Count begs and gains

forgiveness from the Countess. The new section is

andante,

with an

altogether unprecedented stillness and simplicity, half hymn-like,

without Mozart's ordinary glitter:

The complexity of the Finale prior to this moment has been

criticized as excessive. But the point is surely that its very excruciation

plays wonderfully into the serenity of the resolution; the musical tech–

nique itself emphasizes the essential articulation of the plot. The plot

in tum illuminates the characters by its denouement. This

is

a mo–

ment of realization, almost an epiphany, for the Count, who shows

an unsuspected capacity for contrition, with none of the breast–

beating of the mock-pleas by Figaro and Susanna a moment before.

The Countess has never been more lovely and true to herself, less

caught in the artificialities of her existence. Even the Basilios and

Cherubinos are touched. And the characters themselves illuminate the

central dramatic idea: the scene uncovers a core of decency under

all the shabbiness which the comedy has exposed and tried to ra–

tionalize in laughter. All this is possible because

musically

it is a

climax, because the music at this section has a deeper seriousness and

a new clarity of feeling. Yet what effect would the section make out

of its context? It depends on the rest of the Finale, with its striving