An Pham: Reflecting on my 2021 Summer Fellowship with the City of Chelsea

By An Pham (Undergraduate, Economics & Mathematics, Kilachand Honors College)

This summer, I worked with the City of Chelsea as an IOC undergraduate Open Data Intern. I worked with Cate Fox-Lent, my supervisor, on a project to start Chelsea’s new Open Data Hub, where I got to process and curate city data for the public to interact with. As the Business & Grants Manager of Chelsea’s Department of Public Works, Ms. Fox-Lent guided me through learning ArcGIS tools, collaborating with city staff, and coding for the public. I’ve never spent two months quite like it.

My experience during my IOC fellowship was grounded in my academic interests, coding skills, and most importantly, my hometown of Toronto, Canada. Toronto’s downtown is dominated by concrete and steel, with sleek if not cold landmarks like Nathan Phillips Square or the CN Tower. There are beautiful red buildings with green copper rooftops, but they don’t loom over clouds and tourist photos in the same way. I suspected the “real work” was being done elsewhere, a block down the road and a few dozen office floors above. Hence, my impression of government was always tinted a corporate silver-gray.

Chelsea felt different. Almost everything in its 2.46 square miles is within walking distance. Its City Hall is surrounded by busy bus stops and local restaurants rather than skyscrapers. Its predominantly Spanish-speaking population makes Chelsea a visible minority-majority city with unique needs and services. Non-profit groups like La Collaborativa often work with Chelsea’s City Hall to promote government programs, reach non-English speakers, and better provide services.

Whenever I entered City Hall, I passed staffers helping residents fill out forms on plastic foldout tables near the front steps. Inside, more residents lined up on the first floor to ask questions and pay their bills, often in cash. Although my daily impressions were no substitute for the lived experience of Chelsea’s residents, they made sure I remembered who I was working for.

Getting Started

I was overjoyed when Chelsea and the IOC let me start as early as possible. After finishing my spring exams and finding a summer apartment, I started working remotely on Tuesday, May 11th. I went in-person for the first time that Thursday, May 13th, and cycled through workweeks with at least two days in-person.

Most of my work involved ArcGIS. Chelsea’s public datasets had geographic components, so I learned about geographic information systems (GIS) to handle them. My coding experience made the technical parts easier, but ArcGIS involved new concepts and ways of thinking.

I spent the first week learning the basics through official courses that came with Chelsea’s staff ArcGIS license. As with any technical skill, there were troves of free resources online, but access to Chelsea’s license gave me a solid footing and showed me what to search for. It was immensely rewarding to start learning from industry standard software. I completed those courses through the summer and found free alternatives that I continue learning from today.

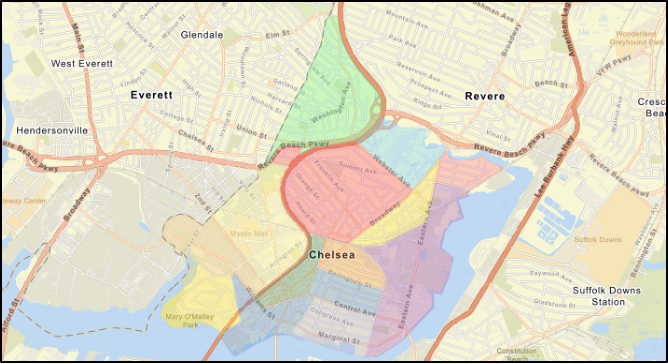

My first ArcGIS task was to draw a map of Chelsea’s city borders and neighborhoods. The neighborhoods aren’t officially defined, so Ms. Fox-Lent showed me multiple city maps as sources, even drawing over printed maps to show me major dividing streets. I zoomed into a digital map of Chelsea and drew polygons point-by-point along those streets. It gave me a sense of Chelsea’s human geography, where people lived and worked, and practice for my new skills. I ended up using the neighborhood map as a background for most Chelsea GIS projects, as it gave a quick sense of where anything we mapped was located in the city.

The Office

After a few days at the City Manager’s office, where Ms. Fox-Lent was the city’s Innovation & Strategy Advisor, I followed Ms. Fox-Lent up to the Department of Public Works (DPW) as she became their Business & Grants Manager. The DPW handled Chelsea’s public utilities and many infrastructure projects. I settled into the “intern desk” directly under a large map of planned sewer upgrades. Thick lines running alongside streets were labelled with estimated prices (up to the millions) and completion dates (up to 2050).

I was nervous to settle into my first office job but learned to listen curiously. Just net to my desk was the DPW water cooler, and countless conversations about field work, city dilemmas, and professional life. I eventually asked questions, picking up context on long-running projects and small lessons on urban planning.

I remember how one staffer explained the history of Chelsea’s sewers and DPW’s long-term aspirations for them. I remember another showing me a cabinet with service cards from the 1920s and explaining DPW’s project to identify and replace lead service pipes. While there were countless lessons from kind staff, one story that stuck with me was how Fidel Maltez, the DPW Commissioner, patiently explained construction bids, electricity grid upgrades, and let me listen in on office meetings. I felt driven from soaking it all in — and a bit tired from the enthusiastic nodding — by the time I got an official lanyard.

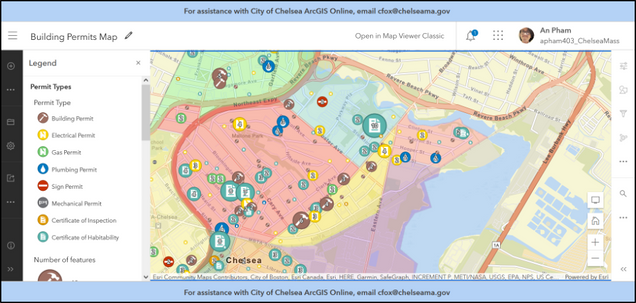

Projects

My work was divided into multiple projects that developed concurrently. The major projects were to map property violation tickets and building permits. Every month, the Inspectional Services Department (ISD) compiles a spreadsheet of all tickets and permits issued, with additional information about addresses, fees, and property owners. The end goal was a WebApp where citizens could interact with ticketing and development patterns across Chelsea. I converted those addresses into GIS points that could be mapped. I returned to both projects multiple times as I learned new ArcGIS tools, polishing their presentation and interactive features.

Throughout the summer, my remote days often involved finding tutorials and experimenting with ArcGIS on my own. Ms. Fox-Lent encouraged me throughout, providing her experience with ArcGIS and feedback on my experiments. It reminded me of learning how to code for the first time, diving through rabbit holes and forum answers. Working for something gave me direction though. If a user-manual had twelve sections on turning addresses into coordinates, I just had to pick the three that might work.

Updating the maps was easy at first. I ran the reports through a Python program on my laptop and uploaded the GIS-ready results to ArcGIS. I was very interested in automating the process using a Python API, and spent time developing tools non-coding staff could use to continue projects after I left. The result was an ArcGIS notebook. It let staff prepare spreadsheets for GIS in their browsers, with no installations and minimal steps.

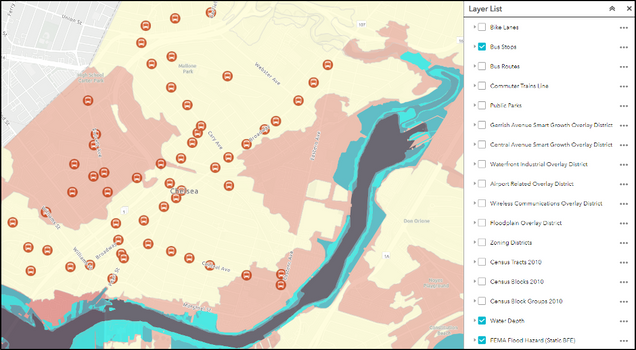

Other maps required less technical preparation and more careful presentation. I combined existing GIS data on Chelsea’s zoning districts and flood information to create an interactive multimap. Ensuring that the very different layers all had coherent color schemes, icons, and meaningful pop-ups was a challenge. I also made maps for Chelsea’s future bike lanes and water-discharge locations.

The most challenging project was linked to the DPW’s goal to replace lead service pipes. DPW wanted to locate properties that might have lead service pipes but didn’t know the status of most properties. They planned to have a specialist go through a cabinet of old service reports to look for mentions of lead. As a start though, I took a GIS file of Chelsea’s property lots and began marking them by hand using current field reports. Whenever a contractor or inspector visited a property, they would report if its pipes were lead or clean copper. Although most properties remained gray for their unknown status, unknown lots surrounded by lead reports would be a starting point for future inspections. An older intern, Fernando Mazzoni, went a step further in dividing the property lots into buildings. We used a spreadsheet of every water meter to map service lines to addresses in the hopes of increasing accuracy. By the time I left, we had preliminary maps showing what Chelsea did know and our own database of water meters with coordinates.

Wrapping Up

My fellowship in Chelsea ended on Friday, July 2nd. I handed in my Chelsea GIS Guide and got to speak to most members of the office one-on-one. They described their careers, why they worked at Chelsea, and gave advice I couldn’t have learned in another room. It was a series of small, meaningful talks that mirrored the experience of small, meaningful projects over the summer.

While I built my technical skills in Chelsea, a bullet-point list of GIS tricks can’t tell the whole story. I gained professional experience doing tasks around the DPW office, scanning vehicle documents, requesting quotes for truck vinyls, making fliers for a city program, and more. The little tricks and conversations I picked up just being around City Hall employees added up to a newfound familiarity with government. It means so much to me that I can better picture career paths in public service, and the type of days they might entail.

I left Chelsea with newfound skills, confidence, contacts, and ideas for what to do next. Working with data through GIS and other systems changed how I think about government and my place in it. This fall, I’m using my GIS experience to join Boston University’s International Relations Review as their first in-house mapmaker. As my academic knowledge of economics and statistics builds during the school year, I know my time in Chelsea will contextualize my time in class. I hope it eventually works the other way too, and that I’ll look back at Chelsea with deeper understanding and ideas for what we could’ve done differently.

I am immensely grateful towards the Initiative on Cities for organizing this opportunity, Ms. Cate Fox-Lent for her guidance and support, and the welcoming staff of Chelsea City Hall. I look forward to the official launch of Chelsea’s Open Data Hub and their future data-focused projects. Like I said before, I’ve never spent two months quite like it. I’m glad I had the opportunity to have this personal and professional journey.

Learn more about IOC fellowship opportunities here.