New Database by IGS Researchers Reveals Inequities in Exposure to Energy Infrastructure

A team of IGS and School of Public Health researchers are uncovering energy exposure hotspots and setting the stage for a more just energy transition.

By Alison Gold

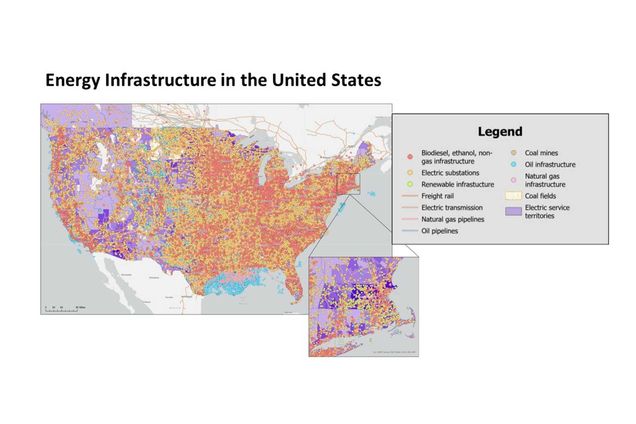

While a doctor may wish to prescribe a patient cleaner air or water, they cannot. Public policy and historical inequities largely influence a person’s exposure to the structural and environmental factors that affect their health. Preliminary analyses from a new database at Boston University indicate that 91% of United States census tracts are within a health-relevant distance of a piece of energy infrastructure, much of it fossil fuel-based, and that energy infrastructure is more densely concentrated in majority non-white census tracts.

Researchers at Boston University’s Institute for Global Sustainability (IGS) developed the database to equip policymakers, academics, community groups, and environmental justice organizations with information to understand who is most burdened by fossil fuel hazards and to advance equitable policies that minimize harmful exposures. Currently, the team is working to map existing energy infrastructure and the populations who live nearby across the United States. They ultimately intend to link this repository to data about population-level health outcomes, and make the tool freely available online through the Harvard Dataverse Repository.

Co-Principal Investigators Jonathan Buonocore and Mary Willis, both of whom are core faculty at IGS and assistant professors at the Boston University School of Public Health (BU SPH), unveiled the Energy Infrastructure Exposure Intensity and Equity Indices (EI3) Database at the May 7 Power & People Symposium hosted at BU. Their work was funded through IGS’s year-long Sustainability Research Grant, in partnership with SPH, to advance research at the nexus of sustainability, health, and equity.

“In my experience, the most compelling thing, the thing that cuts through the noise more quickly and sharply than anything, is data,” said Matthew Tejada, senior vice president of Environmental Health at the Natural Resources Defense Council, in his keynote address at the symposium.

“We are in the beginning stages of a revolution, in our country and globally, in terms of how we make energy, where we make energy, how we use that energy,” Tejada said. “The fact that we’re just now getting in touch with our legacy energy system and the impact it has had on communities over time to today is incredibly important because that sort of data can cut through the noise. It can help communities understand where they are and where they might be going. And it allows advocates, decision-makers, and academicians to engage in a conversation grounded in the realities that communities are experiencing.”

The connection between energy and health

Energy infrastructure abounds. Power lines carry electricity overhead, freight transports biomass cross country, power plants are embedded where people live and work, and oil storage tanks, extraction wells, refineries, and pipelines are hidden in plain sight. These structures keep lights on, buildings functional, and cars running, but researchers are still learning how they impact surrounding neighborhoods.

Many research teams have examined the relationships between particular pieces of energy infrastructure and discrete health outcomes, like the effects of natural gas flaring on asthma, oil extraction on preterm births, or power plants on mortality. A study published last year by Buonocore and colleagues found that regional air pollution from oil and gas production causes approximately 7,500 deaths and $77 billion in health impacts in the United States annually.

By examining just one exposure at a time, these studies reveal only part of the story. Communities often face several hazards simultaneously, which can cause overlapping health effects undetected by traditional, targeted studies.

“One thing that is so powerful about [the EI3] dataset is that it really makes the connection between energy policy and public health policy. They are intertwined and they have profound impacts on each other,” said Andee Krasner, a volunteer at Mothers Out Front and a panelist at the symposium. “Energy policy touches every part of public health, from chronic disease to reproductive health to vector-borne diseases to pediatric health to emergency management.”

A powerful tool to promote environmental justice

Buonocore and Willis began work on the database after identifying gaps in the existing literature on the connection between energy, equity, and health. While the information underlying the database is public, it is scattered between multiple agencies and jurisdictions. Additionally, cross-state comparisons are challenging, as states are often subject to different rules for reporting. The EI3 Database represents the first time anyone has compiled all of this varied data into a harmonized national tool.

“We wanted to gain a fuller understanding of the health and environmental justice impacts of full energy systems, rather than just focusing piecemeal on different pieces of the energy infrastructure,” Buonocore said. “And we wanted to expand the focus of health research to all components of the supply chain, not just focusing on the power plants and the wells, but looking at the full system. And third, we wanted to be able to compare the health and environmental justice implications across different energy types.”

The EI3 Database assesses hazards throughout the supply chain, including extraction, processing, storage, transmission, and distribution.

“Energy infrastructure is a highly common exposure in the United States, yet is not necessarily one we are always thinking about, especially in the population health world,” Willis said. “Persistently marginalized populations are disproportionately burdened with this industry, which aligns with what we know from other pieces of research.”

Early results from the database confirm that energy infrastructure is much more densely concentrated in majority non-white census tracts.

“As director of the Fifth National Climate Assessment, I understand the value of data sets and tools like the one being presented today to address these complex challenges at the intersection of climate change, energy infrastructure, human health, and environmental justice,” said Allison Crimmins, director of National Climate Assessment at the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, at the symposium. “For a long time, these variables have been siloed into their own fields or data sets or reports.”

Broad applicability across industries and sectors

Nearly 150 individuals from more than 20 local and national organizations registered to attend the symposium and learn about the EI3 Database, demonstrating the tool’s versatility. Attendees and speakers joined from government agencies including the Massachusetts Department of Public Health and the United States Department of Energy, nonprofits such as Environmental Defense Fund, HEET, and Sierra Club, and advocacy groups like Greenroots and Mothers Out Front.

Researchers from across BU contributed to the project’s development, including IGS Associate Directors Emily Ryan, an associate professor in the College of Engineering, and Henrik Selin, associate dean for studies and professor of international relations in the Frederick S. Pardee School of Global Studies.

In academia, the EI3 Database opens the door for an infinite number of potential research projects. It could be applied to uncover fundamental learnings about how many people live near pieces of energy infrastructure, to what extent persistently marginalized groups are disproportionately affected, and what levels of key pollutants are emerging from understudied pieces of infrastructure. Meanwhile, community advocates and environmental justice organizations may use the data to understand which communities should be prioritized for renewable energy infrastructure. For policymakers, the EI3 Database may help determine where future climate infrastructure should be sited. This work all serves to establish a fair and just transition to a clean energy future.

“I’m really excited and inspired by researchers like you, who are focused on health exposures from energy infrastructure, who are breaking those silos and telling a more nuanced, complex story, one that really captures the real-life interactions between people and the planet, the real-life consequences of our choices,” Crimmins said. “I don’t think we can truly solve the climate crisis or address the legacies of injustice in this country if we don’t examine those interactions, if we don’t have the data to examine those interactions, and to inform policy decisions around achieving a just energy transition.”