Flaring of Natural Gas in Guyana: Why Is It Happening, and How Can It Be Minimized?

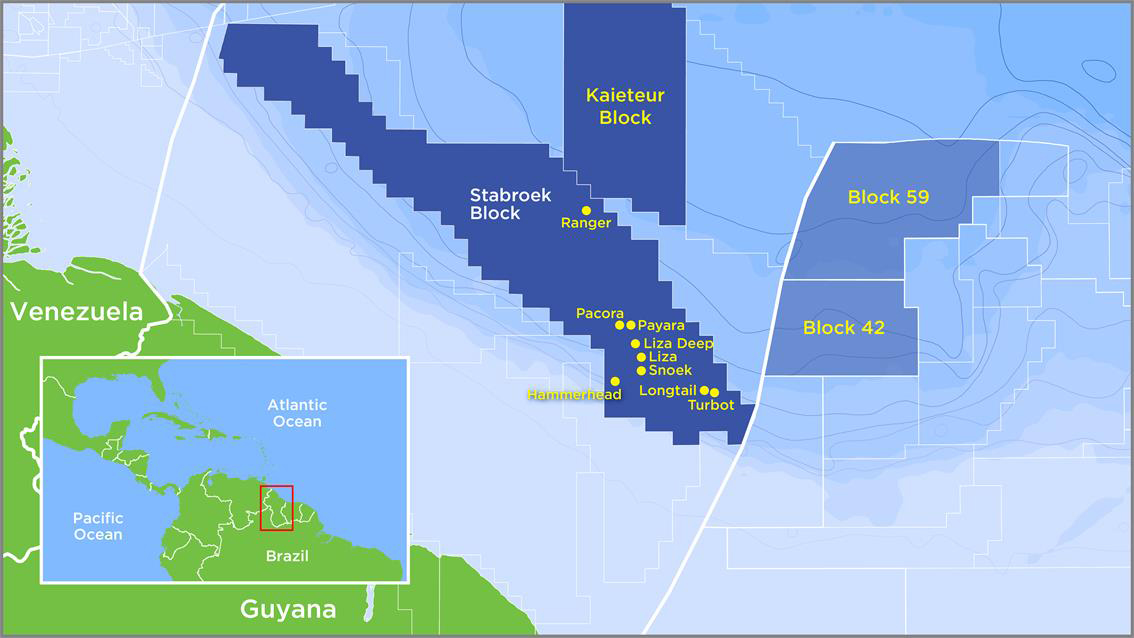

Guyana, a small nation in northeast South America, has featured prominently in energy news lately. ExxonMobil and others have found very large oil reservoirs off the coast, and are presently ramping up production there. One of the main finds is the Liza field, 190 km offshore in water depths ranging from 1500 to 1900 meters. Well depths exceed 5000 meters below sea level.

As is often the case in offshore wells, large quantities of natural gas are produced with the oil. Field development plans call for this gas to be reinjected into the reservoir. This is sound petroleum engineering practice. Unfortunately, ExxonMobil has encountered problems in reinjecting the gas and is, therefore, burning it off (“flaring” it) until it solves equipment problems. Flaring wastes the gas, a valuable natural resource, and emits carbon dioxide into the atmosphere without a beneficial use. Local reports indicate flaring is being reduced as the technical problems get solved, but 9 billion cubic feet of gas have been flared in the meantime. This is more than a day’s consumption of natural gas in the nation of Germany.

At a minimum, the government and people of Guyana should ask ExxonMobil to live up to its own environmental standards. ExxonMobil is a member of the Methane Guiding Principles organization, which in November 2019 issued the most up-to-date and comprehensive guide to flaring reduction.

According to local reporting, flaring is due to problems in gas compression systems. From a technical standpoint, this is not very surprising. The Liza field is very deep, which makes gas compression challenging. There is no question ExxonMobil is capable of deploying adequate gas compression systems to solve the present problem. However, I would recommend that the equipment, as it ages, be monitored for leaks of natural gas, which has a much stronger greenhouse gas effect than flaring. In a study of 45 gas compressor stations in the U.S. natural gas transmission and storage system, two were found to be “super-emitters” of methane (the main component of natural gas), with leak rates much higher than expected. ExxonMobil should have a plan for promptly detecting and repairing natural gas leaks and other equipment breakdowns that will occur in the future, without having to resume excessive levels of flaring.

How does flaring affect climate change? Flaring emits carbon dioxide into the atmosphere for no beneficial purpose. Moreover, inefficient flaring is worse than efficient flaring. Ideally, a flare completely converts natural gas to carbon dioxide. However, an inefficient flare allows some of the natural gas to escape unburned into the atmosphere. Unburned natural gas has a much stronger effect on climate change than carbon dioxide, as explained in work I presented to the American Geophysical Union last December (reference document 1; document 2). Therefore, ExxonMobil should certify that they are using the best available technology to ensure flare combustion is as efficient as possible.

If some of the natural gas could be brought to shore for domestic energy uses the effect would be very positive for Guyana and for global environmental welfare. Electricity generation in Guyana is mostly dependent on diesel engines. Diesel fuel is relatively expensive and has a significant greenhouse gas impact. Natural gas is far superior, both in cost and in environmental effects. Moreover, natural gas has been found to be a useful complement to renewable sources of electricity, such as wind or solar. Unlike the renewable sources, electricity generated from natural gas is “dispatchable,” which means it is always available and can be turned on and off quickly.

Globally, the use of fossil fuels will have to be phased out to avoid dangerous climate impacts. Until that process is complete, oil and gas producers are responsible for minimizing environmental effects. To this end, flaring should be reduced as much as possible, and when flaring is absolutely necessary it should be as efficient as possible. Leaks of natural gas should be found and fixed without delay.

Robert Kleinberg, a Senior Fellow of the Boston University Institute for Global Sustainability, recently worked for the Guyana Ministry of the Presidency as a reviewer of candidates for the position of Petroleum Development Advisor. He is Principal of Presidio Energy Technology and adjunct senior research scholar at the Center on Global Energy Policy of Columbia University.

Related Reading:

- Blog Commentary by Robert Kleinberg

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Boston University Institute for Global Sustainability.