The Land Gap: How Conservation Can Make Sovereign Debt Crises Less Common

By Rebecca Ray

Globally, conserving nature is a key priority for protecting communities and economies from the catastrophic impacts of climate change. To this end, nations around the world have signed the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework and committed to mobilizing $200 billion per year for global biodiversity conservation, including $30 billion through international finance. However, the countries most in need of conservation support are also to international financial markets, because biodiversity losses make countries more prone to economic fragility and frequent debt crises.

New Boston University Global Development Policy (GDP) Center research, included as a chapter in the 2025 edition of the Land Gap Report, traces these connections between sovereign debt crises, environmental damage, climate change vulnerability and economic fragility, leading ultimately to more frequent debt crises, creating a vicious cycle. The chapter includes a case study of how these trends interact in Cameroon and explores avenues toward a more productive, virtuous cycle of institutional and fiscal capacity building, biodiversity conservation and climate change resilience.

The Vicious Cycle of Debt, Nature and Climate

When developing countries face debt crises, they often undergo a process of debt resolution accompanied by austerity––frequently in the form of cutting government payrolls––and a push to boost commodity exports. GDP Center research shows that, when countries turn to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for support during such process, their agreements typically required tightened national budgets, except during the crisis years of 2009 and 2020.

Imposing austerity during a commodity export drive risks deepening a country’s commodity dependence without adequate environmental or social oversight of these intrinsically sensitive sectors. For example, recent GDP Center research finds that IMF agreements are associated with a nine percent increase in deforestation rates annually, compounded over multi-year agreements.

Resulting ecological degradation can lead to reduced ecosystem services. The services can include rainforests regulating rainfall on cropland downwind or coastal wetlands protecting against flooding and tropical storms. Any reduction of those ecological services will ultimately impact the economy as a whole––and particularly those commodity sectors that are most dependent on weather, such as agriculture. These impacts leave countries more vulnerable to extreme weather events. In effect, it reverses progress on climate change adaptation.

Extreme weather events––which are occurring with greater frequency and intensity as climate change takes hold––bring human and economic devastation. They force government to increase spending even as tax revenue fall due to declines in income and consumption after a natural disaster. In these cases, governments will need to borrow, but their borrowing costs typically rise after a disaster. Credit rating agencies now factor countries’ vulnerabilities to extreme weather into their bond ratings. These factors make future debt crises more likely, perpetuating a pattern of debt crises, commodity dependence, environmental destruction and economic fragility. A recent issue of the Journal of Globalization and Development delves into the many ways climate change-driven extreme weather is affecting economic growth and fiscal space across the Global South, including specific spotlights in climate-vulnerable countries in Africa and in Central America and the Caribbean.

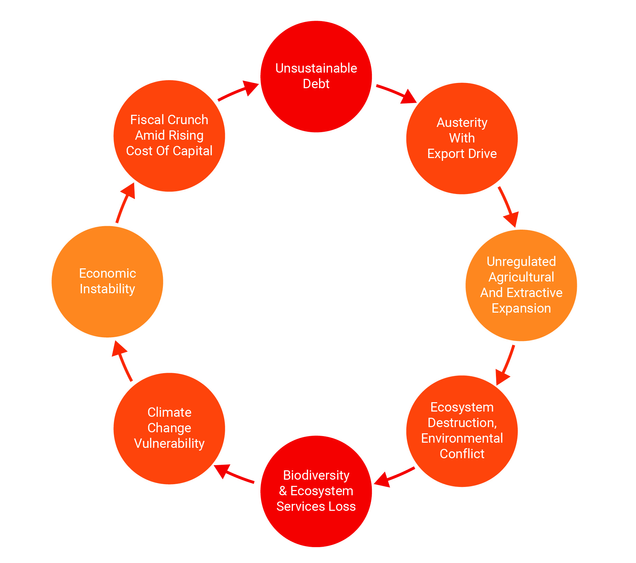

Together, these factors create a vicious cycle: if sovereign debt crises are met with austerity and commodity export drives, then those debt resolution processes plant the seeds of the next debt crisis, through weakening the basis of robust and climate-resilient economies. Figure 1 illustrates how this cycle connects environmental and economic harms, trapping countries into deeper commodity dependence, diminished ecosystem services, greater climate vulnerability, more fragile economic prospects and more frequent debt crises.

Figure 1: The Business-As-Usual Vicious Cycle Connecting Debt, Nature and Climate

Case study: Cameroon

The Congo Basin country of Cameroon illustrates these relationships clearly. In the last five years, Cameroon’s external public and publicly guaranteed (PPG) debt payments ballooned from 11.7 percent of its exports of goods and services in 2018 to 36.0 percent in 2023. In recent years, these payments have accounted for over four times the level of government expenditures on health and over half of government expenditures on education.

Over these years, Cameroon has signed two agreements with the IMF to support its debt restructuring processes. These agreements have required tightening national government budgets in all but one year (2021, as Cameroon continued to struggle with the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic), with cuts of up to three percent of GDP each year. To meet these targets, the IMF advised Cameroon to cut fuel subsidies, effectively passing on the economic pinch to households and businesses.

At the same time, the global prices of some of Cameroon’s top commodity exports have soared. The price of cocoa has grown tenfold since 2020. Facing rising fuel costs and the potential to earn more amid rising cocoa prices, Cameroon’s cocoa producers have vastly expanded their operations: Cameroon’s exports of cocoa have more than tripled in the last decade.

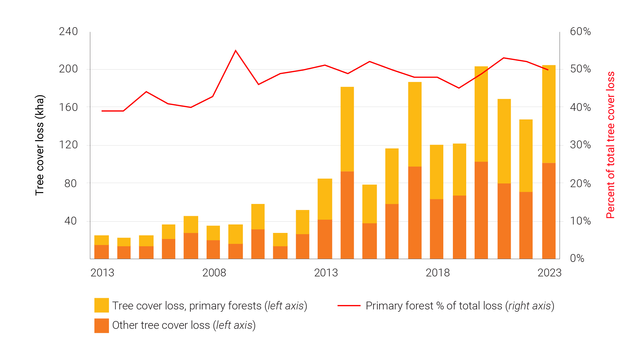

As this agricultural commodity production has expanded, Cameroon’s forests have receded. Figure 2 shows the dramatic jump in tree cover loss, particularly in the last decade. In the most recent years, more than half of this loss has come from primary forests. These losses impact Indigenous communities in particular: like many tropical forest countries, Cameroon lacks legal protection for Indigenous lands. Thus, under-regulated commodity export drives will likely put Indigenous lands at risk from encroaching commodity agricultural producers. Civil society reports attest to over 60 percent of traditional Indigenous “sacred forests” being lost in the last 30 years.

Figure 2: Cameroon’s Tree Cover Loss by Type, 2003-2023

As impactful as these losses have been for Cameroon’s forests, they also threaten the same agricultural sectors that are driving deforestation. Cameroon is one of the world’s most climate-vulnerable countries, and that is particularly true for its agricultural sector, which has one of the world’s lowest irrigation rates of just 0.1 percent. Any interruption or decline in rainfall will seriously damage Cameroon’s harvests. That rainfall is currently safeguarded by the very forests that are under threat; damaged or destroyed tropical forests (including in the Congo Basin) bring reduced and more volatile rainfall levels.

Cameroon’s overall economy is paying the price for this growing reliance on a few commodities and the resulting increase in climate change vulnerability. In a recent sovereign bond ratings update, S&P Global specifically noted risks from volatile commodity prices and climate-related events. Thus, these environmental factors are also economic factors, as they push down Cameroon’s sovereign bond ratings and thus push up the interest rates that the nation must pay on its debt. Ultimately, a more climate-vulnerable economy and higher costs for borrowing will make a future debt crisis more likely, potentially leading to Cameroon’s being trapped in the vicious cycle illustrated above.

A Virtuous Cycle of Economic and Environmental Resilience

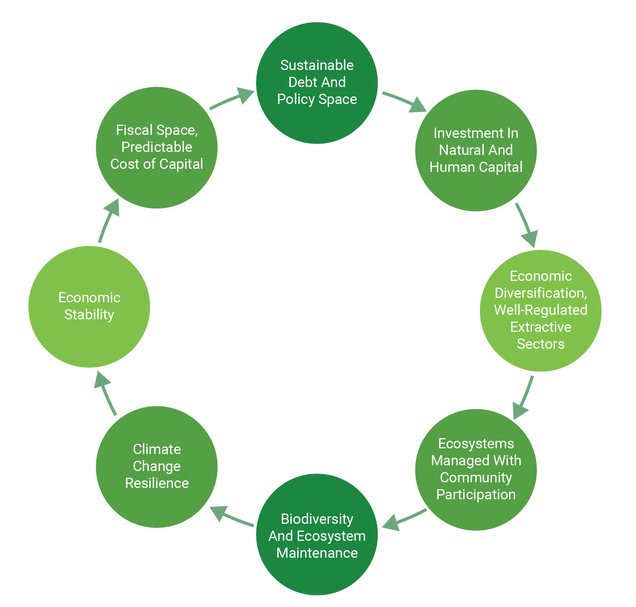

Another approach is possible and necessary. To build a more resilient future, nations need the fiscal space to build institutional capacity and invest in natural and human capital. Figure 3 illustrates a potential “virtuous cycle” of conservation, participation and effective regulation.

Figure 3: Virtuous Cycle of Conservation, Participation and Effective Regulation

Three main steps can pave our progress toward the virtuous cycle shown in Figure 3. First, the Debt Sustainability Analyses (DSAs) that support debt restructuring processes must reflect a realistic understanding of the institutional, natural and human capital investments needed for nations to move beyond commodity dependence. Currently, while DSAs have built in considerations of economic risks from climate change-related extreme weather events, they should also capture the important economic benefits of natural and human capital. Doing so would make it clear how austerity will further erode those benefits and make national economies more climate-vulnerable.

Secondly, the IMF can play a constructive role by reducing its reliance on austerity targets and building in protections for the most vulnerable communities and the ecosystems that support them. Once DSAs clarify the national pathways between austerity, reduced ecosystem services and climate vulnerabilities, the IMF can target protections toward the most at-risk ecosystems and communities. Recent GDP Center research finds that less than one in 1,000 IMF conditions targeted forests, and these were not universally supportive of conservation: some recommended loosening regulations on exports of forest products. Protecting this natural capital is a crucial step for the IMF to work productively with borrowers to build a longer-lasting and more resilient recovery.

Finally, lenders need a more functional approach to debt resolution than the current G20 Common Framework for Debt Treatment. Recent GDP Center research outlines several fronts for reform of the Common Framework that can help it include a greater number of debtor countries, a greater number of lenders and a deeper approach to debt restructuring and building solid fiscal futures. For example, the Common Framework includes only G20 bilateral lenders, which account for only a minority of the debt carried by developing countries. Expanding it to include other lenders under a “fair comparability of treatment” plan can allow for very different types of creditors (including multilateral development banks and bondholders) to participate. Other proposed reforms include opening the process to middle-income debtor countries and making negotiations more transparent and streamlined.

Building – and conserving – a resilient world

Looking forward, creditors, debtors and multilateral institutions each have a constructive role to play in ensuring that debt crises become less frequent and no longer trap developing countries into cycles of commodity dependence, environmental destruction and climate change vulnerability. Given the way ecosystems support economies globally––not just within the national borders of each country, it is in everyone’s interest to work toward a world economy built on robust natural capital from intact ecosystems. To do so will require cooperation and progress toward better debt resolution systems: an ambitious task but one essential for a resilient 21st century for biodiversity and the global economy that relies on it.

*

Read the 2025 Land Gap Report 阅读中文博客