Melania Trump Visits Opioid-Exposed Infants at BMC

Amid protest outside, First Lady sees unique cuddling program for mothers and their babies up close

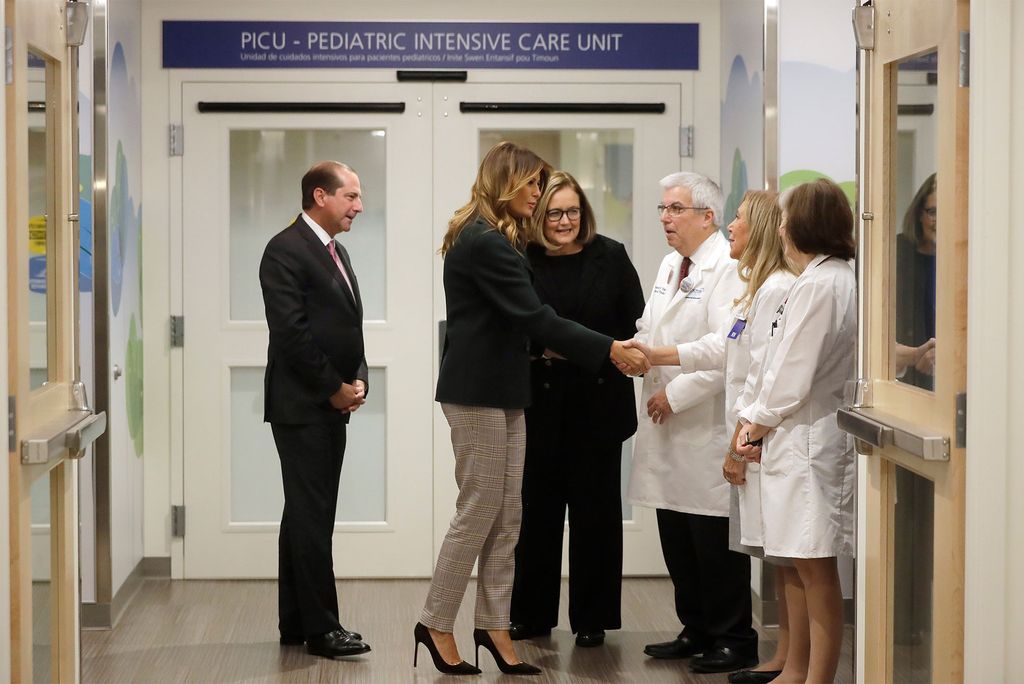

First Lady Melania Trump with US Secretary of Health and Human Services Alex Azar (from left), Kate Walsh, BMC president and CEO, Bob Vinci, BMC chief of pediatrics, Karan Barry, BMC Pediatric Intensive Care Unit nurse manager, and pediatrician Eileen Costello during her visit to Boston Medical Center. Trump was informed about the hospital’s Cuddling Assists in Lowering Maternal and Infant Stress program (CALM), which works to help mothers with substance use disorders and their infants born with neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS). Photo by Steven Senne/Pool/AFP via Getty Images.

First Lady Melania Trump visited Boston Medical Center on Wednesday to learn about a unique program at the hospital that helps mothers and their newborns born with prenatal opioid exposure by encouraging as much skin-to-skin contact as possible.

Her visit sparked demonstrations outside the hospital, with more than 100 doctors, nurses, and other BMC affiliates gathering on Moakley Green to let the hospital administration know that they oppose welcoming Trump because they believe many of President Trump’s policies have been harmful to the families, members of the LGBTQ community, and disadvantaged populations that BMC serves the most. One protestor’s sign read: “Our BMC Cares for All,” another: “Exceptional Care, No Exception,” and a third: “Cuddles not cages.”

Inside, the focus was on the center’s Cuddling Assists in Lowering Maternal and Infant Stress (CALM) program. As part of her visit, Trump met with families and infants getting support from the program, which has successfully treated infants and mothers since it was launched in 2016. “I hope today’s visit helps shine a light,” Trump told the media that attended. “It is my hope that what we discuss today will encourage others to replicate similar programs within their own communities.”

By using a nonpharmacologic approach to opioid-exposed infants—including the CALM program, along with intensive, supportive care—BMC has seen significant changes. Before that strategy, 86 percent of infants with opioid exposure were treated with medication, but that figure has since dropped to between 30 and 40 percent.

BMC has a long-standing commitment to treating opioid addiction. Earlier this year, led by Jeffrey Samet (SPH’92), BMC chief of general internal medicine and a Boston University School of Medicine professor of medicine, the hospital was awarded $89 million from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to reduce opioid overdose deaths by 40 percent in 16 Massachusetts communities.

Prior to the First Lady’s visit, Kate Walsh, president and CEO of BMC, emailed BMC’s 6,000 employees, saying she hopes “the visit will be a unique opportunity to share our values of respect and inclusion with federal leaders whose policies have a significant impact on the vulnerable populations we are dedicated to serving.” She added that Trump’s visit is a chance to highlight successful programs like CALM.

Elisha Wachman, a MED associate professor of pediatrics and CALM faculty advisor, founded the cuddling program, and since its inception has consistently seen that simple human contact can dramatically benefit infants born with neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS), a withdrawal syndrome newborns experience after being chronically exposed to opioids during the mother’s pregnancy.

In the early days of the program, Wachman and her team studied the percentage of time a parent was at an infant’s bedside and found the amount of time spent with the newborn was directly correlated with a happier, healthier baby.

“This was the first time someone said, wow, it actually makes a big difference to have someone there, it’s directly correlated with how the baby is going to do,” says Wachman. According to her research, nonpharmacologic care significantly reduces the need for medication and the amount of time the babies spend in the hospital after they are born.

According to the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, opioid-related deaths have increased more than 500 percent since 2000, with more babies being born exposed to opioids. The number of infants born with NAS in the United States has jumped fivefold, to about 5 per 1,000 live births. In Massachusetts, the rate is even higher, 20 per 1,000 live births. The commonwealth has started to see an incremental slowdown in the number of deaths from opioid use in the past couple of years, but the issue remains widespread across Massachusetts and the country.

One of the goals of the First Lady’s Be Best campaign is to provide support and education to families and children affected by the opioid epidemic and bring wider public attention to NAS. During her Boston visit, Trump, who was accompanied by US Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar, also received a briefing on several other programs at BMC aimed at assisting pregnant women with substance use disorder (SUD).

After a mother with SUD gives birth at BMC, clinicians monitor the newborn for withdrawal symptoms and provide comfort and support when it’s needed. And as one would imagine, the wait-list to be a volunteer baby cuddler is long. Volunteers go through training before taking shifts that are typically one to two hours between 8 am and midnight, when the babies are most likely to need extra care.

“A lot of these mothers have a lot else going on in their lives,” Wachman explains in a video the School of Medicine created about the program, in which medical students participate. “So there’s times when they can’t be at the bedside, at which point a CALM cuddler can step in.”

The protest that took place outside was largely silent, with no speakers, just a group of employees gathered together.

“We’re here standing in solidarity with our community, who has been attacked by the Trump administration,” says Tiffany Rodriguez, a BU School of Public Health student and part of BMC’s Vital Village Network. “Everything we do here at BMC stands for increasing access to healthcare—it stands for women, it stands for immigrants, LGBTQ healthcare. We will not be complacent, and we do want to let everyone know that BMC staff is for the community.”

BMC infectious disease fellow Karim Khan, who joined the protest, also said the group was there to stand with impacted community members. “A lot of our patients come from communities that have been specifically targeted by the Trump administration,” he says. “We want our patients to know that [BMC] is a safe place to come and get care.”

In her note to BMC staff, Walsh said: “As the largest safety-net hospital in New England, our relationship with the federal government is extremely important. Two-thirds of our patients have some form of government insurance, and our health plan is the largest participant in the state’s Medicaid accountable care organization, so the opportunity to highlight the innovative work we are doing is critical to ensuring that we are able to continue to deliver on our mission well into the future.”

Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley (D-Mass.) released a statement Wednesday saying that Trump’s visit is “a chance to remind and educate the Secretary and First Lady of the ways in which our medical centers work to eliminate disparities and ensure that all people, regardless of income and immigration status, have a fundamental human right to healthcare.”

BU Today staff writer Amy Laskowski contributed to this article.

Author, Jessica Colarossi is a science writer for The Brink. She graduated with a BS in journalism from Emerson College in 2016, with focuses on environmental studies and publishing. While a student, she interned at ThinkProgress in Washington, D.C., where she wrote over 30 stories, most of them relating to climate change, coral reefs, and women’s health. View her profile.