Events

BUCPUA alumna, Beya Jimenez, leads #BUcity Co-Lab Week event on anti-racist city planning for racial equity

On Oct. 29th, over a hundred Zoom attendees—faculty, staff, students, and members of the public—came together to attend the third-to-last event in the #BUcity Co-Lab Week, entitled “Anti-Racist Cities: How Planners Can Champion Racial Equity in the Field.”

The event was moderated by CPUA’s very own Beya Jimenez, who now serves as Director of Economic Opportunity with the Greater Boston Chamber of Commerce and who focuses on engagement to close the racial wealth gap.

The event featured a slew of panelists in the planning and public health fields to discuss how they have championed anti-racist policies and plans in their own work to achieve racial equity.

The panelists included: Jessica Martinez, a transformative development initiative fellow with MassDevelopment; Courtney Lewis, a regional planner with Metropolitan Area Planning Council; Joyce Sanchez, a senior specialist on the stakeholder management team and capital delivery division with National Grid; and Dr. Meghan Venable-Thomas, a culture of health leaders fellow with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and a cultural resilience program director with National Initiatives.

Jimenez began the event with a call to action to address racial inequity within planning, such as redlining and the displacement of Black and brown people from their neighborhoods through gentrification, as well as on a broader societal level, with systemic racism and the silencing of Black, Latinx, and Native voices.

“We need to act now. We need students who are engaged and ready to ask tough questions. We need planning professionals who won’t sit on the sideline,” said Jimenez.

City planners play an important role in standing up for equity and “upsetting the set-up,” or disrupting the status quo and established systems that are a stronghold of racial inequity, said Jimenez.

Jimenez began the panel discussion by giving panelists the opportunity to share how they have been taking care of their mental health as Black and brown people of color in 2020.

Sanchez responded by saying that she takes moments to step back and do things that bring her joy, like writing poetry, taking walks, and reading books. In addition, Sanchez said she sees her work as a “silver lining” and opportunity to uplift the community.

“What uplifts me is my role as a stakeholder manager,” said Sanchez. “It brightens my day when I can address a concern with a resident or business owner.”

Dr. Venable-Thomas brings together her passion for public health with her passion to decolonize wellness by working at TrillFit.

“What we know in public health is that communities who are most likely to succeed are socially connected,” said Dr. Venable-Thomas. Wellness is one way to establish social connections between communities and encourage better mental health, said Dr. Venable-Thomas.

Jimenez then asked the panelists about the racial and gendered disparities that have been revealed by the COVID-19 pandemic, and how to address the call to action against racism under the looming public health threat of the pandemic.

Dr. Venable said in her work with Mass Design Group, she has come to realize that design is not neutral––it either harms or it heals––and that planners play a unique role in impacting the future disparities of the communities they work with. “Planners have to see that they’re not just a planner or a designer,” said Dr. Venable-Thomas. “You’re also a health practitioner, you’re a cultural practitioner, you are the place where people spend most of their life.”

“Create a community that is focused on creating thriving places,” said Dr. Venable-Thomas, “where people can have dignity, home, safety, security, and feel good about where they live.”

Lewis chimed in saying that “as planners of color, we have a responsibility to advance racial equity in the community,” especially since urban planning has perpetuated institutional and systemic racism in our cities and towns.

Like Dr. Venable-Thomas, Lewis said that planners wear many hats when it comes to their impact on the community. “We [as planners] have to recognize that we are positioned at the nexus of urban design, public health, and economic opportunity,” said Lewis. “We have to be agents of change to undo disparities caused by the built environment.”

Sanchez said that the public and private sector play an important role not only in the wake of the pandemic, but in addressing and combating racial inequity. National Grid has taken up this responsibility through their Grid for Good program, which provides mentorship to socio-economically disadvantaged youth between the ages of 16-24.

The next question concerned changing demographics in gateway cities, a designation that describes post-industrial cities in the state of Massachusetts.

Martinez took the floor to answer this question, explaining that her recent work with Lawrence, MA has worked toward establishing dignity and stable schooling and jobs.

“Gateway cities offer really good bones to a city,” said Martinez, who said planners should see their work as “gardening,” as putting work and love and care into the community in order for it to grow and thrive on its own.

Lewis said his work at MACP has focused on using an equity lens to take an introspective look at the policies and practices planners use, and making sure planners “are actually walking the talk.” Specifically, Lewis said MACP has created the REMAP program, which works with six different communities to develop and operationalize racial equity plans.

Jimenez then asked the panelists what advice they would give current Black and brown student planners, as well as advice they would give to themselves five years ago?

Sanchez listed three tenets of advice she would give to current students and herself: 1.) Don’t underestimate networking, 2.) Never stop networking, and 3.) Know your worth.

“As a person of color, as an educated person of color, don’t sell yourself short,” said Sanchez. “Ask a company how effective their current diversity initiatives are and if they have any benchmarks tracking how effective those initiatives are.”

Lewis said to learn as many different topic areas within the planning profession as possible and take advantage of every opportunity to express thanks and gratitude to those working alongside you.

“You are worth more than anything someone can compensate you for,” said Lewis, “because of the unique blessing you bring to the world. Your best should bever be compared to someone else’s best.”

Dr. Venable-Thomas said that student planners of color should “use their experience as a person of color as their expertise,” and to see that experience as that which should be lifted, heard, and valued..

“When we show up as our full selves,” said Dr. Venable-Thomas, “we lift up those residents whose voices and bodies and experiences are at the table in how we do development and design.”

Then, the panel discussion ended and Jimenez encouraged the audience to ask the panelists questions.

One of the questions asked was: How do we inspire underrepresented students that aren’t typically exposed to planning and design?

Martinez said we need to teach young people that planning is a survey course, and that you can go into so many different fields with a planning background.

Lewis said it’s important to create a pipeline that exposes high school students to planners of color, because representation matters.

“My first introduction to urban planning was Sim Town,” said Lewis, “It wasn’t until I was in college as an undergrad that I understood that this is what I want to do.”

Another question posed by an audience member asked how safe and inclusive streetscapes can be planned and designed for people of all backgrounds, and what a paradigm looks like.

Martinez said that inspiring imagination in people––planners and community members alike–– is important in the design of inclusive streetscapes for communities, as well as piloting to engage with the community.

In response to an audience question about how to use the current moment to champion racial equity and public health, Dr. Venable-Thomas said the current moment is “an opportunity for Black, indigenous, people of color to interrogate their own trauma and healing, because decolonization starts with you [an individual] in addition to the system.”

Lewis said we should “capitalize on this moment to push for zoning reform across the Commonwealth.”

Anne Jonas, CAS '21

BUCPUA professor Emily Keys Innes presents this fall’s #BUcity keynote lecture, “The Early Days: Next Steps”

On Oct. 28, Emily Keys Innes, director of planning at Harriman and CPUA adjunct professor, presented her keynote lecture, “The Early Days: Next Steps” to a group of eager students, faculty, and CPUA community members.

The lecture began with a literary introduction, an epigram by Alasdair Gray––borrowed from Dennis Lee’s 1972 “Civil Elegies”––which reads: "Work as if you live in the early days of a better nation.”

The epigram, Innes said, gives us “a moment to think about how we rise to meet challenges,” many of which are “something larger than what each of us can do alone.”

The power of the planner and their work, then, is to make the active choice to be present in the world. And that work, Innes said, is “at its base about creating a new future. What we do is a deeply social act. Our work requires us to collaborate with others into acts that will shape the future of the communities in which we live.”

Innes guided her presentation by analyzing individual words from the epigram. She began with the word “world,” explaining that as humans generally, and as planners specifically, we move through countless intersecting worlds throughout our day.

Whether it be the roads we drive on, the neighborhoods we drive through to get to work, the buildings we work in, etc. we must consider how each world intersects with one another and consider the lived experiences of the people in those worlds.

The first step as a planner in addressing these worlds is “defining the world you want to make better,” said Innes. The second step, and perhaps the more challenging one, is understanding that your experience of that world is not always shared by all.

Whether it be zoning that perpetuates social inequalities, or urban renewal that strips neighborhoods of their culture, it can be difficult for residents and planners alike to imagine ways to make the world better.

But, Innes said, it’s not impossible, and planners should strive to begin again, to find out what better means and how to get there. To do this, Innes transitioned into her analysis of the words “early days.”

Using the play Hamilton as an example of collective action toward a specific moment, Innes said it’s important to expand our relationships with one another (and with ourselves) in order to bring our vision of possibility, of what the early days should and could look like, to fruition.

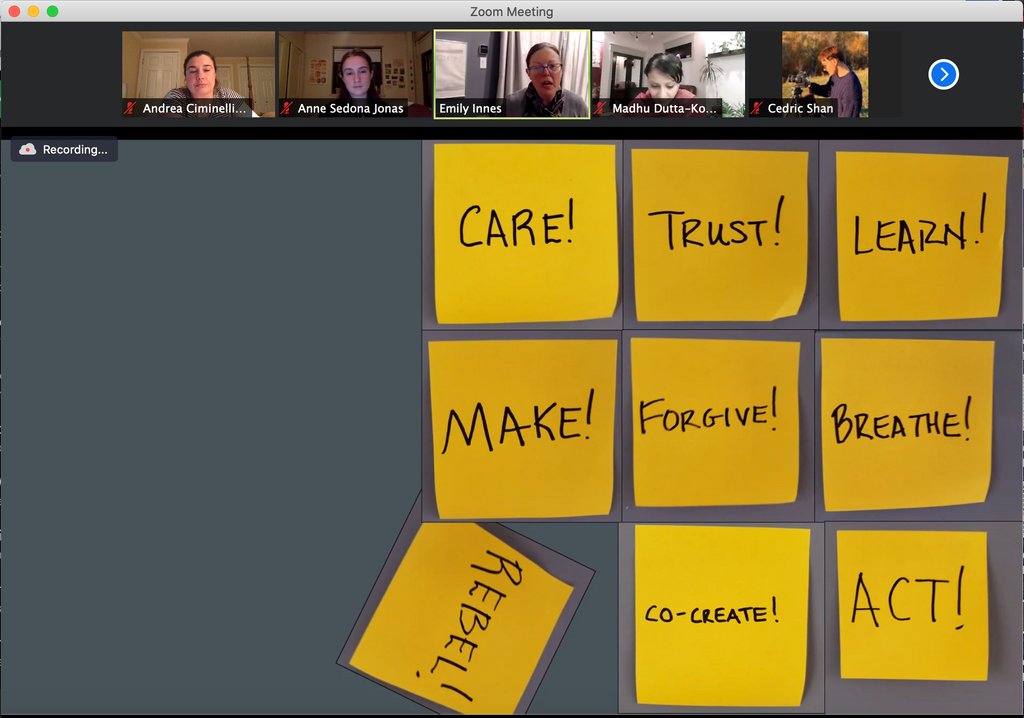

To unpack this relationship-building, Innes identified nine words which serve as “guideposts” to her journey as a planner. The nine words she chose were: care, trust, learn, make, forgive, breathe, rebel, co-create, and act.

To accompany each word, Innes included nuggets of wisdom:

“Care: Care because every decision you make as a planner has an impact on people.”

“Trust: Trust people, especially those you disagree with. Allow new voices into the conversation and trust that their voices will add to the conversation. And trust yourself.”

“Learn: Be humble about what you don’t know.”

“Make: Do something physical with your hands, ignore time as you create, put your tools where you can see them.”

“Forgive: You will run into some seriously nasty people in your career, but you must focus on your larger goal, on your purpose that brought you to planning.”

“Breathe: “Learn to be alone in perfect silence.”

“Work: The most important part of being a planner is that you will accomplish nothing without collaboration. You cannot build without agreement, and you cannot get agreement without compromise.”

“Rebel: Try new things, but think through the norms before you disrupt them.”

“Co-create: Find real joy in working with others to create. Community resiliency is how we work.”

“Act: Our actions have more impact than our words. We cannot argue for the importance of local economies if we buy all of our goods from far away. We need to act by making choices and mistakes and trying again. Our actions must lead to a better world.”

Innes then ended her keynote lecture by asking all attendees to choose a word from her list and send her an email on April 28th, 2021 about the word they chose and what they did with it.

After her lecture, Innes took audience questions on topics ranging from race relations in Boston, the intersection between city planning and public health, bureaucracy, and affordable housing.

Anne Jonas, CAS '21

#BUcity Co-Lab participants learn about visual communication, portfolio design, and personal branding from BUCPUA’s very own David Valecillos

David Valecillos is a graduate of the BUCPUA Master in City Planning who now works with the North Shore Community Development Corporation as the director of design. Valecillos is also a founder and director for the Punto Urban Art Museum, an open air museum in the El Punto neighborhood of Salem, MA.

On Tuesday, Oct. 27, Valecillos led the third event in the #BUcity Co-Lab Week with a presentation called “Visual Communication for Urban Professionals: The Why and How?” about his work as a city planner and designer.

Valecillos began by explaining that growing up in Venezuela, “a rich country naturally, but with high inequality,” led him to pursue city planning as a way to “understand the intersection of communities and socio-economic divides.”

His work in Salem has brought this interest to fruition. Salem is the second most visited city in Massachusetts, with most tourists visiting in October for the spooky, witchy history of Salem’s colonial past.

While the downtown area receives much attention and tourist attraction, the El Punto neighborhood, which is situated just adjacent to the downtown area, receives little to none. Like Roxbury and Dorchester, El Punto is segregated from the downtown, even though it is just blocks away.

The El Punto neighborhood is a mostly Hispanic neighborhood, with 80 percent of residents from the Dominican Republic. The neighborhood, which was primarily French-Canadian in the early 1900s, used to be an industry center for blue-collar, factory workers.

Valecillos wanted to address the segregation of the neighborhood from downtown Salem as well as the stigma that is associated with the neighborhood, with causes detriment to its residents. To address these concerns, Valecillos developed a plan for community engagement in 2012, which reached 300 people in the neighborhood.

From this plan, some common goals were established: improving housing infrastructure, improving public infrastructure, and reducing the stigma associated with the neighborhood.

Putting these goals into action, Valecillos made 50 units out of 150 into affordable housing, and established a community space for residents in the building to hold events.

The North Shore Community Development Corporation now owns 300 units––30 percent of the neighborhood––and has rehabilitated 200 of the units. Included in this rehabilitation were parks and sports facilities, such as a basketball court which features art chosen by kids in the neighborhood in collaboration with a local artist.

Art is a major part of Valecillos’ work, and it is used to bridge the gap between the El Punto neighborhood and downtown Salem, as well as bringing the community together to erase the stigma of the neighborhood through restorative place-making.

95 large-scale murals have been installed across the El Punto neighborhood, with the collaboration of 75 artists from across the world, but especially artists from Hispanic backgrounds. These murals became what is now the Punto Urban Art Museum, an open air, public museum celebrating the culture of the El Punto neighborhood and its residents.

To help launch the museum and the neighborhood gain traction from the public, Valecillos rebranded the organization and rebranded the webpages. The organization's worth expanded from $2 million dollar to $3 million as a result.

Valecillos transitioned into the design component of his presentation, emphasizing the importance of technology for young urban planners as they develop their portfolio and brand themselves for future employers.

When is the time to start thinking about your portfolio? Now!

The first step in developing your portfolio, Valecillos said, is identifying how your past projects, life experiences, skills, and education make you a desirable candidate for future employers, and from there, identifying what kind of work you envision yourself doing and succeeding at.

Your portfolio should be an act of storytelling, emphasized Valecillos, that is realized through a few key elements in the design process of your portfolio.

The key elements Valecillos highlighted were: color and text, formatting, general content, and layout.

Within these elements, there are subsections as well.

For example, when choosing the color and text of a page in your portfolio, the first step is choosing your color palette, followed by selecting a font style, and lastly, by organizing the visual aspects of the page into a hierarchy. Larger, brightly colored, or bolded fonts are more eye-catching and therefore higher in the hierarchy than smaller, lightly colored fonts.

Within the formatting element, Valecillos said to identify a type, as well as an orientation and flow. The pages of your portfolio should be formatted consistently so that the reader has a clear picture of what problems in your project or work were presented and how you solved them.

The general content and layout of your portfolio should include: a cover, your contact information, a short bio, an index, and project summaries.

The presentation ended with questions from the audience on gentrification, affordability, and instilling a sense of community.

Valecillos said that it’s important for city planners to have an ear-on-the-ground to listen to the communities they are working with to ensure that they are not imposing, and that any changes are made collaboratively, hopefully easing the fear of gentrification and change.

Anne Jonas, CAS '21

BUCPUA kicks off #BUcity Co-Lab Week with panel discussion on tools for inclusive and accessible city planning

The City Planning and Urban Affairs Program kicked off its #BUcity Co-Lab Week–– a series of events, panel discussions, and workshops running from October 26th through October 30th –– Monday night with a panel discussion event co-sponsored by BU Sustainability, and moderated by Sustainability’s own Erica Mattison, assistant director of communications.

The event, “Planning Tools to Support Streets for Everyone,” offered up advice, resources, and perspective from five industry experts on how city planners can––and should––design accessible, inclusive projects.

The five panelists covered a variety of backgrounds and experiences within and outside of the field of city planning.

“I landed in this field by mistake,” said Anabelle Rondon, program director of Great Neighborhoods with LivableStreets, who first got involved in the community development field by working at a non-profit and specializing in Latino businesses.

“I fell in love with finding out the specific needs of the community,” said Rondon, whose work specializes in the intersection between housing, transportation, and climate.

Nigel Jacob, co-chair and co-founder of the Mayor’s Office of New Urban Mechanics, is also invested in an on-the-ground approach to community involvement and development.

“When I left grad school, I was looking for a mission,” said Jacob. “My mission has stayed the same: try to change the way local government works.”

And he’s doing just that by engaging with communities via technology and design––literally.

Beta Blocks is his most recent project. The project aims to “explore how to teach people to interrogate their built environment,” said Jacob, by placing technology on streets to engage with community members and give them a platform to share opinions and concerns.

Marion Decaillet, director of inclusive public transit at the Institute for Human Centered Design, is equally concerned with and fascinated by connections with people, which is why she was drawn to transportation.

“I love to connect people to each other,” said Decaillet, “I love the physical connection.”

Decaillet works to provide accessible, inclusive public transportation by designing and planning projects with a holistic approach.

“We need to make sure that there is a connection between the project we want to deliver and the demographic we are serving,” said Decaillet. “We cannot design in a vacuum.”

Elijah Romulus is the assistant town planner for the town of Bridgewater, working in land use development and managing different energy projects and policy proposals.

Romulus had been involved in community work well before working in the public service, and it is this interest that led him to pursue city planning, after completing his undergraduate degree as an engineer.

“I started organizing in my hometown of Brockton,” said Romulus, “And as I was doing that community service work, I wanted to combine my engineer experience and activism passion."

Jimmy Pereira, the community and transportation planner with Old Colony Planning Council, was led to city planning after completing his bachelor's degree in geography and regional planning with a minor in ethnic and gender studies.

“Planning is very interdisciplinary,” said Pereira, who, from the beginning of his career looked at the ways the built environment and active transportation, like bicycling, were interconnected.

Pereira worked with MassBike in the years prior to improve cycling, make sure that roads and infrastructure were safe for cyclists and drivers alike, and to reduce emissions by encouraging more people to take up biking.

Some of the most important and challenging problems and issues facing planners today is making sure communities are as involved as possible in the planning process, but this proves to be much more difficult in practice than in theory.

Rondon, who worked with the New York City Housing Authority on a planning process in the South Bronx, said a common mistake she sees in her work is translating the language of the plan to the greater community, across languages and the busy lives of community members.

To solve this problem, Rondon implemented coffee hours, a plan to “bring planning to the people.” Rondon and her team brought coffee into the lobbies of public housing buildings to listen and translate the concerns of the people about gentrification and the changes to come.

“We should be meeting people where they are,” said Rondon.

Pereira echoed Rondon, saying that planners should have a boots-on-the-ground approach with low-income and English as a Second Language communities to provide as much transparency as possible.

“We try to cast the net and drag it back in and see what we have,” said Pereira, who said the pandemic has resulted in a method of outreach moving toward video and audio, with literature moving to the backseat.

This poses problems, though, for low-income communities who might not have access to wifi. As a result, there is “a lot of sifting in the dark,” said Pereira, to try to find an approach that is inclusive of the population but also accessible to their needs and limitations.

Romulus said that one of the more positive things to come out of the pandemic is that public engagement has increased two, sometimes three times as much as years prior, in terms of the amount of people attending meetings.

Rondon said that COVID has amplified advocacy and the need for policy change, placing the demands on decision makers to actively listen to community members. Rondon added that COVID presents a unique opportunity to push change and to challenge the status quo.

In tandem with the pandemic, the Black Lives Matter movement has pushed America toward a racial reckoning and re-evaluation of how the government serves its people.

“What does innovation look like in the era of trying to make city hall anti-racist?” asked Jacob. “How do we redesign the way decisions are made?”

These questions, although rhetorical, can be answered via “shining light on the root cause of some of these issues,” said Romulus, like looking at questions of abolition, looking at where public money and tax payer dollars do, and looking at how to be proactive as opposed to reactive.

Part of these changes are a move toward a more ecological and sustainable future for cities.

Romulus said the town of Bridgewater plans to add a fleet of hybrid vehicles to its current fleet and install charging stations on Town Hall’s campus, thus reducing the carbon footprint. The town of Bridgewater is also retrofitting LED lights to streetlights, replacing older halogen lamps to reduce energy usage, brighten up streets for pedestrian safety, and save money.

After the panel discussion, Mattison opened the floor to audience members to ask questions to the panelists.

Audience members asked astute questions about specific resources for inclusive city planning––panelists recommended reaching out to non-profit organizations in your community, as well as MassDot and the Mel King Institute.

Another question concerned local zoning laws and the NIMBY (Not In My Backyard) Movement. Rondon answered this question, explaining that Massachusetts has a unique web of state laws that haven’t been updated since the 70s, causing 351 cities and towns to decide on zoning laws on their own because there is no state-level operation to handle that. Rondon said that voices need to come to the table to discuss opinions so that some change can be made.

Romulus echoed this, saying that a city planner is a change agent and a power-broker, working with stakeholders and trying to come to some middle lane.

For more information on CPUA’s Co-Lab Week, visit https://www.bu.edu/cityplanning/bucityco-labweek/

Anne Jonas, CAS '21

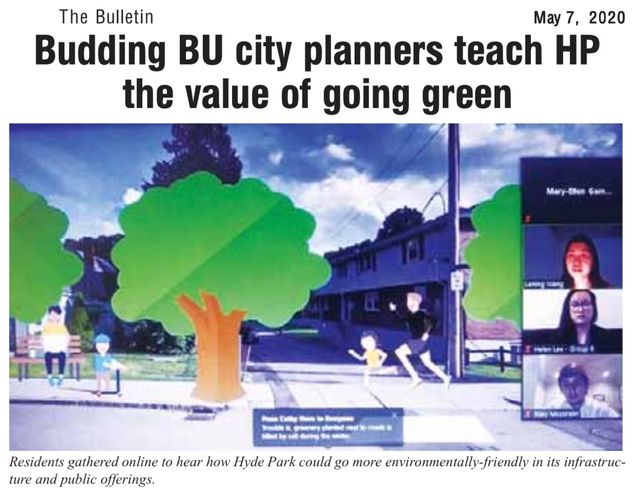

Urban Studies Capstone Proposes Green Opportunities in Hyde Park

By MET Marketing

May 15, 2020

As reported in the Hyde Park Bulletin (Volume 19, Issue 19), on May 5 students from Metropolitan College’s Urban Studies Capstone course (MET UA 805) presented The Power of Green! Strategic Proposals for the Hyde Park Community. The virtual event focused on actions that could be taken to enhance access to, and quality of, the neighborhood’s green spaces, and provoke economic development in the Hyde Park central business district. The four proposals will be made available to the public.

“We want our students to be agents of change,” says Associate Professor of the Practice Madhu C. Dutta-Koehler, director of the City Planning & Urban Affairs programs, and a resident of Hyde Park. “This is a unique neighborhood that needs to be celebrated. Our hope is they will work in the community when they graduate.”

A key course in the Metropolitan College City Planning & Urban Affairs programs, the Urban Studies Capstone is designed to integrate the principles and applications of city planning, urban affairs, and public policy while fostering interdisciplinary partnerships and helping to cultivate industry alliances and cooperation.

Learn more about the Class of 2020 on the City Planning & Urban Affairs website.

Special thanks to fellow Terrier and author of the article, Mary Ellen Gambon (COM’94, CAS’94). Read the full article in the Hyde Park Bulletin.