BU Profs Take Energy Conservation from Lecture Hall to Real Life

Assessing, revamping energy use at Roxbury’s Madison Park Village

The next time you walk into an office lobby that’s freezing on an August afternoon or an apartment that’s sweltering on a January morning, consider this: buildings are energy hogs, responsible for more than 40 percent of all of the energy consumed and the carbon emitted in the United States. So, improving buildings’ heating, cooling, and electrical systems would seem a no-brainer. But curbing a building’s energy consumption isn’t as simple as flipping a switch; better technology must align with building occupants’ attitudes and behaviors to ensure the highest level of efficiency.

Four Boston University professors have recently taken on that challenge, teaming up with BU’s Sustainable Neighborhood Lab (SNL) to see how they can improve energy efficiency at Madison Park Village, a low-income housing complex in Roxbury, Mass. City councilor Tito Jackson, who represents Roxbury, first connected BU staff and faculty with representatives from theMadison Park Development Corporation nearly two years ago to discuss how to improve the complex’s energy use. The team was able to tackle the project thanks to grant funding from IBM and Wells Fargo.

Jim Quirk, a Wells Fargo vice president, says the project fit nicely with the bank’s philanthropic mission of supporting basic clean technology solutions. “We’re really not interested in a solar panel on a $10 million townhome in Louisburg Square,” he says. “That’s nice, but that’s not really what we want to do. We’re looking for a significant impact for someone, not a feel-good project.”

The timing of the project works well for Madison Park Village, which is undergoing an extensive renovation. Russell Tanner, the corporation’s director of real estate, says the energy project also “gets residents more engaged in the process and more cognizant of the impact on their lives.”

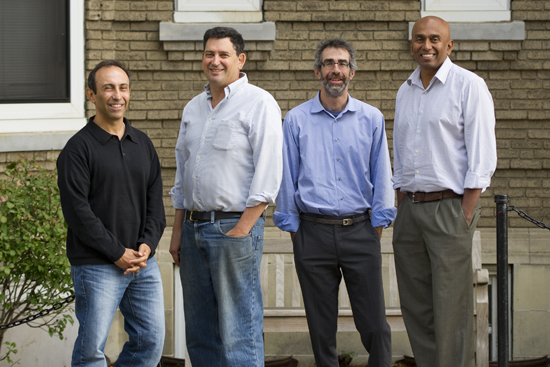

The BU team is taking an interdisciplinary approach by drawing on each of the members’ field of expertise. Robert Kaufmann, a College of Arts & Sciences professor of earth and environment, will crunch the numbers to determine variations in energy consumption among the village’s four buildings. Michael Gevelber, a College of Engineering associate professor of mechanical engineering, is determining which energy systems are already in place and whether they are delivering the promised results. Based on his findings, he will make suggestions for ecofriendly technology upgrades. Nalin Kulatilaka, the School of Management Wing Tat Lee Family Professor in Management, will propose financial incentives that could encourage landlords to invest in technology improvements and tenants to use energy wisely. And Enrique Silva, a Metropolitan College assistant professor of city planning and urban affairs, will examine residents’ energy consumption habits to better understand how they could be influenced toward conservation.

What’s neat about this project, Gevelber says, is that “it’s bringing together these four totally different people with different perspectives to work on this…real problem for the city of Boston and for the people who live here.” Gevelber used to meet weekly for coffee with Kaufmann and Kulatilaka to discuss how to translate energy conservation theory into practice. This project now gives them, and Silva, who joined the team at the suggestion of SNL’s administrative director Linda Grosser, a chance to do just that.

Work on the project began in May when the BU team and research assistants designed a survey to assess Madison Park Village residents’ energy consumption and conservation. They recruited and trained a handful of local high school students to conduct the door-to-door surveys, with the goal of collecting 100 by summer’s end. Only 40 were returned completed.

The teenagers ran into unexpected challenges in administering the survey, says SNL project manager Marta Marello (GRS’13), who supervised the youth. Some residents were not available because they worked full-time or had young children who demanded their attention. Others spoke only Spanish or were reluctant to share personal information with relative strangers. Still, the BU professors think they received enough information from the surveys that were returned to compare to utility bills paid by property management and arrive at a baseline for the village’s energy consumption.

Madison Park Village is in many ways the perfect project to study how technology and occupants’ attitudes shape energy conservation, because the landlord pays for electricity and gas in two of the buildings and tenants pay in the other two. The property management team has given BU access to the bills it pays, but the residents who pay their own utilities have been more hesitant to share that information for privacy reasons or out of fear of being judged in the event they have overdue accounts.

“We’re asking for the privilege to go into their homes and poke around with questions and issues that could be embarrassing or incriminating,” Silva says. “You have to be sensitive to the residents’ life situations…without stigmatizing, without making assumptions.” There is a history of researchers swooping in to conduct studies without benefitting the local communities in which they work. The professors’ goal is to “change that paradigm,” he says.

Silva is now in the process of identifying families willing to participate in more in-depth interviews and in-home observations so that he and his colleagues can link residents’ attitudes regarding energy consumption with their actions. What he discovers will help determine which incentives might push residents toward energy conservation. “Technology itself does not nudge people” to change, he says. “It’s how people relate to technology.”

Using a combination of hard data and behavioral observations will help the BU team analyze what Kulatilaka calls the split incentive problem—that tenants living in units with utilities included “have very little incentive to act prudently,” while those paying for their usage do. He thinks a solution lies in providing both landlords and tenants with rewards for energy conservation. For example, if the professors can determine how much money would be saved monthly by installing a new energy-efficient HVAC system within a building, then that money could be passed on through regular payments to tenants and landlords. For every dollar saved, 20 cents would go to the resident, and 80 cents to Madison Park.

Meanwhile, Gevelber is creating an inventory of engineering systems within the buildings, determining whether they are user-friendly and if further upgrades are necessary. Landlords might pass by a window cracked open in the dead of winter and envision dollar signs floating in the air. “We always blame the occupants for wasting energy,” Gevelber says, but one problem could be that “buildings are designed in such a way that there’s no temperature regulation in each room, no way to adjust it, and the system is just running.” He says that’s a mechanical, not a human, problem.

If the BU team’s approach is successful at Madison Park Village, it could become a model for other housing developments in the city. (Kulatilaka says representatives from Dorchester’s Codman Square Neighborhood Development Corp. have already contacted them about the possibility of working with the BU team.) Finding a model that works in Boston could have major global implications, considering that more than half of the world’s population currently lives in an urban area and the World Health Organization projects that 7 out of 10 people will live in a city by 2050.

“If you can solve the problems of the city, you’re going to be able to solve global problems,” Grosser says. Energy use is a big part of that equation. “Cities are a major source of global energy expenditures,” she says, “but they presumably could also be the most efficient consumers.”