Making Art Out of the Mundane

Painter Mathew Cerletty confronts audiences with a vivid, hyperreal take on everyday objects

Sconce (2022) Oil on linen; 58 1/4 x 64 in. (left); Fuel 5G (2022) Oil on linen; 72 x 58 1/2 in. (right). All images courtesy of Mathew Cerletty

Making Art Out of the Mundane

Painter Mathew Cerletty confronts audiences with a vivid, hyperreal take on everyday objects

Everyone with a laptop and a Zoom account had to become an amateur lighting expert during the pandemic, rearranging lamps and closing curtains to make ourselves presentable. So it’s no surprise to me when I see that artist Mathew Cerletty has propped a giant sconce above his desk for a recent Zoom interview.

We start talking about his 2020–2021 exhibit, Full Length Mirror, at The Power Station in Dallas, Tex. But my eyes keep sliding over to the black cone of the sconce. It’s unusually large, maybe four feet tall and just as wide. And it hangs at an odd angle. Then I realize it’s not a real light at all, but a painting, leaning against a wall in the background. So realistic is the metal sheen, and so vivid is the glow of the bulb, the image seems to pop off the wall in three dimensions.

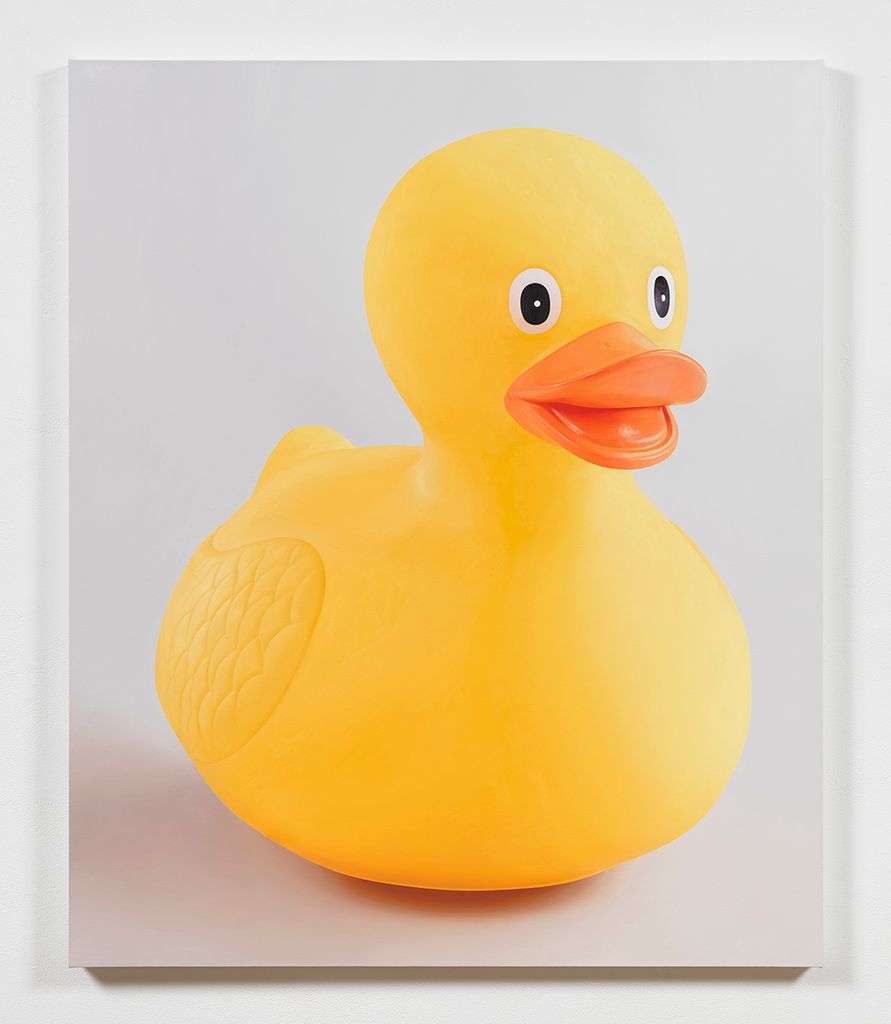

For the past few years, Cerletty (’02) has focused on making hyperrealistic, large-scale oil paintings and colored pencil drawings of everyday items: a stuffed bunny, a wooden laundry drying rack, a green velvet ottoman. There’s no mystery to the objects that Cerletty chooses or the way he portrays them. But their in-your-face presentation demands a closer study—is it a photo or a painting or a drawing? And why did the artist re-create a snow shovel in such painstaking detail?

“The name of the game is keeping people’s attention,” Cerletty says. “If I make a painting and you feel like you can sum it up, that means you can walk away. I’m trying to make it so that every time you see this thing, you’re like, ‘Wait a second—I don’t feel like I quite know what this is about.’”

Portrait of an Artist

Cerletty hasn’t always practiced this form of hyperrealism. He’s painted abstracts and landscapes. Christopher Bollen, in a 2008 story for Interview, wrote, “Cerletty . . . could have remained his generation’s premier portrait artist. But in the last few years [he] went in a completely different direction.” That was when he began making paintings of minimalist text and logos. A surreal space-scape phase followed, briefly. “I started to see a lot of paintings like that around and I felt, like, ‘OK—these other people have this taken care of. I should go do something else.’” That’s when he began working on the pieces for Full Length Mirror.

You’re the One (2020) Colored pencil on paper; 25 x 20 1/4 in. (left); Dry (2019) Oil on linen; 69 1/4 x 52 in. (right)

The vibrant colors and photorealistic details of that exhibit suggest a fully formed style that belies the way Cerletty’s career keeps morphing. Asked to define his work, he demurs. “I feel like I still don’t have a style,” he says. After further thought he says, “Maybe it’s called ‘uptight.’”

That self-deprecating sense of humor is a recurring theme. Cerletty is careful not to take his art too seriously, but simultaneously hopes that his viewers will. “I’m just trying to figure out a way that the images are compelling enough that you’re drawn to them, but also elusive so you can’t quite pin them down,” he says. “It’s a balancing act.”

Step one is finding inspiration, which could happen anywhere—though usually it’s online. “I’m Googling things all the time, going through image search and just scrolling around,” he says. If he likes an image, he prints it and tucks it in a folder. He’s had photos stashed there for years and might ultimately paint one because an object ties together an exhibit he’s working on, or it’s a color he’d like to work with, or the image is just lodged in his mind.

I’m just trying to figure out a way that the images are compelling enough that you’re drawn to them, but also elusive so you can’t quite pin them down. It’s a balancing act.

For his exhibit True Believer at Karma in Los Angeles (on view from November 12 through December 23, 2022), Cerletty wanted to paint a gas can. He searched the internet, but couldn’t find an image he liked. So he had a photographer take one for him. They set up the container in his Brooklyn studio and adjusted the lighting to hit the contoured plastic just so. “It’s perfect in every way,” he says.

It’s a style common in product advertisements, creating a version of an item that is, as he puts it, “a heightened version of itself.” For the gas can photo shoot, he splashed the object with light from multiple directions so every detail is illuminated and the reds and yellows glow. “I’m trying to turn up the volume on a thing.”

Layers of Meaning

“People are always interested in the making of the paintings, but it’s very practical,” Cerletty says. “I don’t feel like that’s where the magic is really happening.”

Most of his artistic decisions are made before his brush touches canvas, when he’s creating or editing a photograph. The lighting, the composition, even the pale yellow backdrop for the gas can serves a purpose. “I wanted it to be a little icky and kind of remind you of the smell when you’re pumping gas,” he says. “All of these formal choices are trying to emphasize a mood and steer the viewer in a certain direction. In the end, hopefully you don’t see all of it right away.”

Ottoman (2020) Oil on linen; 48 x 70 in.

Once his source image is ready, Cerletty projects it onto a canvas, traces its outline, and starts building the painting in layers. Base colors go on first, filling the outline; next, he gradually adds details. It’s a process that can extend over several months, so he also jumps from project to project. He’ll work on the base colors of a painting on one wall of the studio then move over to fill in some of the details on another.

“It does end up feeling like watching a tree grow,” he says. “I finished four square inches today. Great.”

Alongside the gas can and sconce, Cerletty was working on a series of pieces for his True Believer exhibit, including a stack of cardboard boxes, sheets of construction paper, and a large rendering of the sleeve to a Pretty Woman VHS cassette with everything but the name removed.

Pushing the Envelope

For Full Length Mirror, Cerletty painted a pair of overlapping manila envelopes. The backside of one reveals an unbent metal clasp and the adhesive flap; the front of the other is a uniform yellow. They’re basic objects that rarely attract a second thought—but they often hold important documents.

Manila Envelopes (2020) Oil on linen; 58 1/4 x 56 1/4 in.

Cerletty remembers telling his girlfriend that he planned to paint them. “‘Why would you do this to people?’” he remembers her saying. But she finally came around to his perspective: “She said, ‘Fine—you’re making me think about the different times in life where you might be confronted by one of these envelopes and some of them are horrible and some are exciting.’”

The challenge of teasing meaning out of the mundane motivates Cerletty. “Sometimes I go in with the hope that I can rescue something that you don’t want to think about,” he says. “We live in this super-branded corporate world that at times feels like there isn’t room for humanity. The work should reflect that.”