The Art of Creating Artificial Eyes and Facial Prosthetics

Sculptor puts her skills to use making artificial eyes and facial prostheses

By Corinne Steinbrenner | Photos by Mark Fleming

Kaylee Dougherty presses a sculpting spatula to the clay, smoothing the contours of her morning’s work. She pours a mixture of resin and artificial stone around the clay to form a mold; when it’s set, she’ll fill the mold with pigmented silicone to create an astonishingly lifelike final product.

While most sculptors intend for their work to be seen and admired, Dougherty (’11), an associate at Boston Ocular Prosthetics, Inc., hopes that this piece will go unnoticed.

Dougherty is training to become a certified ocularist and recently received her certification as a clinical anaplastologist. As an ocularist, she creates artificial eyes for patients born without eyes, or for those who have lost them to accident or disease. As an anaplastologist, she sculpts facial prostheses for an array of patients—a man who lost his nose to skin cancer, a girl born with an underdeveloped ear, a woman whose eye was destroyed in a car accident.

An associate at Boston Ocular Prosthetics, Inc., Kaylee Dougherty (’11) creates artificial eyes and sculpts facial prostheses. Every piece is custom and matched to her patients’ natural features.

“Everything is custom,” Dougherty says. “Each piece we do is hand sculpted, is hand painted or hand pigmented.” The goal is to match the prosthesis so precisely to her patient’s natural features that her artwork is mistaken for reality.

Dougherty works alongside her employer and mentor, Ottie Thomas-Smith. Both trained sculptors, they fabricate artificial eyes using dental-grade acrylic, adding red silk thread to replicate veins and mixing pure pigment to create custom eye colors. For facial prostheses, they work primarily in silicone, which they tint with dry pigment to match a patient’s skin tone.

Dougherty and Thomas-Smith spend most of their time in Boston Ocular Prosthetics’ main office and fabricating lab in Jackson, Maine, a tiny town southwest of Bangor that provides a peaceful setting for focusing on their work. They also make regular visits to satellite offices in the Boston area, where they meet with patients to take impressions, perform fittings, and provide maintenance. Ocularistry patients make regular appointments just as they would with their dentist. “We like to see our patients once or twice a year,” Dougherty says. “We clean [the eye] and polish it and check it to make sure there’s nothing that needs adjustment.”

All of Dougherty’s patients come through a physician’s referral, and their prostheses are covered by medical insurance because they are necessary, Dougherty says. “They aren’t just cosmetic.”

Kaylee Dougherty (’11) takes us into her fabricating lab. Dougherty was drawn to anaplastology because the field matched her interests: working with her hands, working with people, and making a positive difference in the world. Video by Jason Kimball

A prosthetic ear helps direct sound waves into the auditory canal. A prosthetic nose filters and moisturizes incoming air. An artificial eye keeps the eyelid in position and helps tears drain properly. When a child is missing an eye, the eye socket can cease to grow, causing the child’s face to develop asymmetrically. Wearing an increasingly larger prosthetic eye can stimulate growth of the socket, encouraging normal maturity of facial bones and tissues.

“Everything we make has a purpose beyond just making this person look normal again,” Dougherty says. “Of course, I can [also] put an ear piercing in for a teenage girl. It’s not going to hurt, so we might as well go for it.”

Finding Her Calling

Dougherty chose sculpture as her undergraduate major at Boston University because “I wanted to do sculpture when I was seven years old,” she says. “It’s all I’ve ever wanted to do.

“I love the physical aspect of sculpting—the act of it,” she continues. “But I didn’t ever see myself having a studio somewhere and trying to sell what I was making, or being in galleries. I always wanted to work with my hands, and I knew getting a degree in sculpture would get me the knowledge I needed to do a lot of different things.”

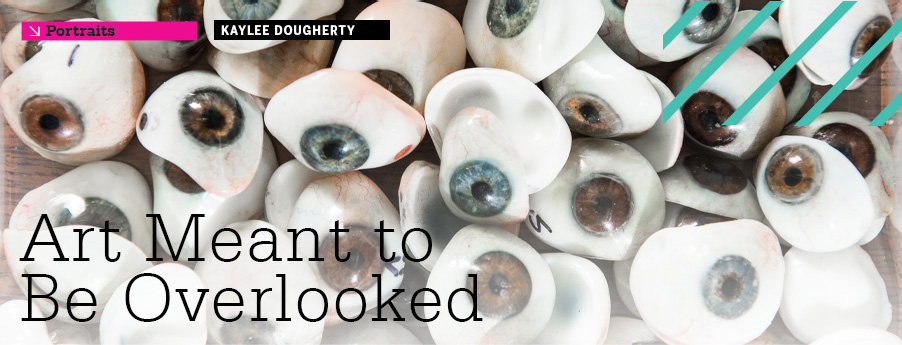

Dougherty fabricates artificial eyes using dental-grade acrylic, adding red silk thread to replicate veins and mixing pure pigment to create custom eye colors.

The School’s sculpture graduates apply their knowledge of form and visual relationships to a range of careers, says Jeannette Guilleman, director ad interim of the School of Visual Arts, from theatre-set design to retail displays to 3D animation.

Dougherty heard about anaplastology during her senior year at BU and immediately recognized it as a field that matched her interests: working with her hands, working with people, and making a positive difference in the world. She researched the requirements to become a certified anaplastologist, which include a combination of scientific and studio-art coursework and three years of supervised training. Through her BU studies, she had already completed all of the required art classes and some of the science classes. After graduation, she took the remaining coursework—medical terminology, human pathology, and human physiology—through BU’s division of graduate medical sciences, and began searching for a mentor to supervise her clinical training.

She was surprised to discover that of the nation’s nearly three dozen anaplastologists, only one was located in New England: Thomas-Smith, who has a dual specialty in anaplastology and ocularistry. Dougherty called Thomas-Smith and asked if she could see her work firsthand. Thomas-Smith had upcoming appointments in her Boston office and invited Dougherty to meet with her there.

“So she came,” says Thomas-Smith, “and I can’t remember specifically who the patients were, but I do remember them being rather interesting. You know, large facial patients—people with portions of their faces missing.” Seeing these cases, she felt, would be a good introduction for Dougherty to the realities of the work.

“The first patient I met,” remembers Dougherty, “was a man with an artificial eye. He came in and sat down, Ottie introduced me, and he just took out his eye and handed it to me.”

“And God bless her,” says Thomas-Smith, “she was interested. She acted extremely appropriately and professionally, was very sweet when asked anything by the patients. There was one patient who lobbied for me to hire her immediately.”

“I always wanted to work with my hands, and I knew getting a degree in sculpture would get me the knowledge I needed to do a lot of different things.”—Kaylee Dougherty (’11)

Creating Relationships

Dougherty joined Boston Ocular Prosthetics as an apprentice in May 2013. She passed her anaplastology certification exam last year, and she expects to take her ocularistry exam in 2018. Thomas-Smith says she looks forward to eventually retiring and turning her business over to Dougherty, who she knows will take good care of her patients.

Building relationships with patients is a large part of Dougherty’s work and one of the things she loves most about it. Her youngest patient was a six-day-old girl born with only one eye. That infant is now a two-year-old who always greets Dougherty with a hug. “My oldest patient is 97,” Dougherty says, “and I go to her house because it’s difficult for her to get down to our office.”

Taking time to know her patients not only makes Dougherty’s work more enjoyable, it can also improve patient outcomes. When she first met John, who had lost both eyes to childhood retinal cancer, she asked him detailed questions about his life and daily habits to help her best meet his needs.

Building relationships with patients is one of the things Dougherty loves most about being an ocularist and anaplastologist. She meets with patients to take impressions, perform fittings, and provide maintenance.

John had been wearing a patch over his most damaged eye socket and an artificial eye in the other. “But because of the radiation [treatments] over the years,” Dougherty says, “he couldn’t wear the artificial eye anymore.”

Dougherty wanted to make John two orbitals—prostheses that replace the eye and its surrounding tissue—but she worried that a blind patient would have difficulty placing two separate prostheses correctly. She asked if he lived with anyone, and John told her that his wife was also blind. Since John didn’t have anyone to help with daily placement, and he’d comfortably worn sunglasses for years, Dougherty borrowed an old-fashioned technique and made him a spectacle-held prosthesis—two orbitals attached to a simple pair of eyeglasses.

“I was able to make him something that was comfortable and wearable that he could use every day and know it was going to be in right,” Dougherty says. “It’s an example of how you really have to talk to someone and get to know the person.”

Dougherty knows that having two lifelike eyes helps John interact more easily with friends and business associates. “I like making a difference on that very micro level,” she says. “It’s one person at a time, but it makes a big difference to that individual person.”

Patients often ask Dougherty if she still makes art. She laughs at the implication that what she’s doing for them—sculpting an ear, painting an iris—isn’t “art enough.” For her, she says, it very much is.