![]()

Departments

![]()

|

Week of 9 April 1999 |

Vol. II, No. 30 |

Feature

Article

U-turn in roadbuilders' direction

New center takes broad look at transportation strategies

By Michael B. Shavelson

When Boston's Big Dig is finished in five years, most of the people gauging the project's success or failure will do so from behind their steering wheel. They will base their judgment on the answer to one question: how long will it take me to drive from Quincy to South Station?

When T. R. Lakshmanan looks at the Big Dig or any other transportation project or system, he tends to do so with his back to the road.

Lakshmanan is a CAS professor of geography and the director of BU's newly established Center for Transportation Studies (CTS). From May 1994 until January 1998 he was the director of the Bureau of Transportation Statistics, a branch of the U.S. Department of Transportation. For him and his colleagues, a transportation system's impact on the surrounding society is generally more meaningful than what happens on the road, the tracks, or the shipping lanes.

"When I returned to BU after four years in Washington," Lakshmanan says, "I wanted to start a new, broad-based program because, nationally speaking, the moment is right."

It's right, he explains, because of a shift in emphasis by transportation analysts and policy planners -- away from the road. "Most transportation studies programs were until recently part of civil engineering schools," he says. "They were not part of the social and behavioral sciences -- economics, geography, sociology, psychology. This is one reason a lot of policy problems have come up, and that's why we are starting the center here. We are located at the College of Arts and Sciences, and most of our faculty are from the geography department. But we are a University-wide center. Our faculty includes Ralph Hingson, from the School of Public Health, and N. Venkatraman, from the School of Management. We hope to establish links with the College of Engineering, too, as we develop our program."

CTS will conduct sponsored research in transportation issues for outside agencies and promote transportation studies for both undergraduates and graduate students. The center's research findings, Lakshmanan hopes, will be used by local, state, and federal policy makers.

Lakshmanan traces many of today's transportation policy dilemmas back to the Interstate Highway Act, signed into law by Dwight Eisenhower in 1956. "What we basically did as a nation," he says, "was put a tax on gas and use that tax at the federal level to support 90 percent of the cost of the interstate highway system. There was so much money flowing into the states and the cities that the only question was how much to build and where. No one ever asked whether or not we should build. There was a remarkable consensus among engineers, contractors, and public officials, all of whom were drinking from the trough of federal money.

"Only in the last 10 to 15 years have we come to realize that we cannot solve transportation problems by simply building our way out of them."

Lakshmanan says that an awareness of environmental, socioeconomic, and public-health issues now helps determine what kinds of systems will be built and where they should be located.

Working in Washington as a Clinton appointee and talking with many of the 50 state secretaries of transportation heightened his appreciation for broad-based transportation studies, Lakshmanan says.

"There have been individuals at BU with an interest in transportation, such as Hingson at SPH, whose interest is in transportation safety. And there are faculty members in the geography department who have taught courses in transportation or have looked at specific issues, such as Bill Anderson, who has studied transportation and energy, Lata Chatterjee, who is interested in transportation and global change, and Ray Dezzani, who concentrates on transportation and trade issues. CTS is the first major effort to bring together a comprehensive research and teaching program."

|

|

|

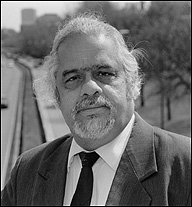

"We cannot solve transportation problems by simply building our way out of them," says Lakshmanan, who poses near Storrow Drive. Photo by Fred Sway |

"To depress such a highway and release land involves putting together so many stakeholders with conflicting objectives," he says, adding that one sign of the Big Dig's success is that most of those competing parties are in fact cooperating. Engineers and planners working with local citizen groups provide an example of where that collaboration can lead: the triumph over the enormous technical problem of building a tunnel while life -- and traffic -- goes on above.

"The way the Big Dig has solved its technical challenges was to invent new solutions," Lakshmanan says, "such as the slurry wall," which allows the removal of earth and the installation of steel and cement without interrupting existing activities. "These solutions, I am sure, will be applied elsewhere and lead to new industries, which will have a great economic impact on the area."

The region is feeling that economic injection now, he says, thanks to the project's massive demands for material, equipment, and labor. But the ultimate effect will come in 2004 with increased road capacity, separation of local and long-distance traffic, and the environmental improvements resulting from less bumper-to-bumper traffic.

CTS isn't studying the rebuilt Central Artery, but the center has just received a commission from the U.S. Department of Transportation to analyze the direct and indirect impact of other highway projects across the country.

"We have to analyze the costs and benefits to different groups," says Lakshmanan. "In making transportation policy decisions, somebody's ox is going to get gored to benefit somebody else. At CTS we principally use mathematical analysis to make the data clear so those policy decisions can be made in a transparent fashion. Certain things cannot be quantified, of course, but where they can be, we base the argument on fact, not on ideology."