![]()

Departments

![]()

|

Week of 6 November 1998 |

Vol. II, No. 13 |

Feature

Article

Talespin artist

Larry Tye puts another spin on the father of PR

by Brian Fitzgerald

He helped sell the American public on the First World War, claiming that it would "make the world safe for democracy." He paved the way for the public's acceptance of women's smoking in the 1920s. Edward Bernays (Hon.'66), often referred to as the father of PR, is even credited with creating and naming the field of public relations.

"Bernays left an indelible mark on our world," says Larry Tye, an adjunct professor in the College of Communication and author of the recently published book The Father of Spin: Edward L. Bernays and the Birth of Public Relations. "He had a profound impact on everything from the products Americans purchased to the places they visited to the foods they ate for breakfast. And yet most Americans have never heard of him."

Tye, a medical reporter for the Boston Globe, says that he decided to write the biography because he felt the public would be interested in how people behind the scenes influence what we purchase, whom we vote for, and how we decide which wars are worth fighting.

|

|

|

Larry Tye

|

Tye also attempts to sort out fact from fiction in Bernays' life, knowing from the outset that the 800 boxes of personal and professional papers that the father of spin left to the Library of Congress would likely contain inflated claims of accomplishment, while his PR failures would be downplayed or not mentioned at all. That is why he interviewed many friends, family members, colleagues, and clients. Tye also talked to Bernays at his Cambridge home "on a sweltering summer afternoon" in 1994, a year before he died at the age of 103.

Bernays' exaggerated claims in press reports first drew Tye to the author of the seminal 1923 book Crystallizing Public Opinion. Bernays, Tye wrote, "professed to know why America behaved the way it did, and he claimed to have a hand in shaping those beliefs." Then during Tye's Nieman Fellowship at Harvard four years ago, he took a creative writing course taught by Bernays' daughter Anne. "She got me interested in her dad," he recalls. "Her husband, Justin Kaplan, a Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer, convinced me that Edward Bernays would make a perfect subject for a book."

Tye did find Bernays' life fascinating. The Vienna native served as an advisor to U.S. presidents from Calvin Coolidge to Dwight Eisenhower, and to a host of celebrities including Enrico Caruso, Samuel Goldwyn, Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, and Henry Luce. Among the clients he turned down were Adolf Hitler, Francisco Franco, and Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza.

Tye also came to the conclusion that Bernays, a nephew of Sigmund Freud, did indeed pioneer the application of the social sciences to public relations. Bernays referred to his method as "Big Think," and he charged big fees for his services. And more often than not, his big claims can be substantiated. Bernays' work for the American Tobacco Company was highlighted by a parade of cigarette-smoking debutantes down New York City's Fifth Avenue on Easter Sunday 1929. The campaign, in which Lucky Strike cigarettes were billed as "Torches of Freedom" for women's rights, remains a classic in the world of public relations, but Tye says that it didn't single-handedly break society's taboo on women's smoking. "Would women have smoked without Eddie Bernays? Absolutely," he says. "But would women smoking have been linked to the women's liberation movement without Eddie Bernays? Not with as much flair."

Saddamnation

Tye begins the biography with a conflict that is still fresh

in the minds of most Americans: the Persian Gulf War, which

he calls a "public relations triumph." Iraqi President

Saddam Hussein, wrote Tye, "was cast as pure villain,

complete with menacing leer and malevolent mustache. It had

Iraqi soldiers snatching infants from hospital incubators

and leaving them on the floor to die while Iraqi helicopters

hovered over Kuwait city and Iraqi tanks rolled down the

streets."

This version of the war, crafted by Hill and Knowlton, one of America's biggest public relations firms, was reminiscent of Bernays' demonization of German Kaiser Wilhelm II more than 80 years ago. Bernays' work during World War I for the U.S. Committee on Public Information became the mold for marketing strategies in subsequent wars.

One of the most interesting chapters in Tye's book is "Going to War," much of it about Bernays' helping to engineer the overthrow of the socialist regime in Guatemala in the 1950s -- a revolution that benefited United Fruit Company, one of his clients. Tye shows how that Cold War propaganda effort "set the pattern for future U.S.-led campaigns in Cuba and, much later, Vietnam."

|

|

|

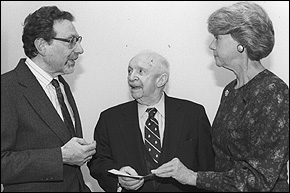

Edward Bernays (center)

visited COM in 1992, soon after he turned 100 years

old, to announce a $5,000 increase in the endowment

of the annual Primus Inter Pares Scholarship that

he created. At left is COM Professor Emeritus

Walter Lubars, then COM dean ad interim. At right

is Kathleen Ladd Ward, president of the Public

Relations Society of America. Photo by Julie Chen-Merritt

|

Otto Lerbinger, a professor of mass communication, advertising, and public relations at COM, witnessed another war Bernays helped engineer: the struggle to save the sycamore trees along Memorial Drive in Cambridge. In 1964, the year Bernays moved to Cambridge from New York, the Massachusetts Legislature proposed spending $6 million on road underpasses on the Cambridge side of the Charles. But Bernays helped organize the Emergency Committee for the Preservation of Memorial Drive, "which made pitches to every interest group Eddie could think of," wrote Tye, "to mothers who were angry about losing their children's playgrounds, to real estate executives who worried about devaluing the high-rent apartments along the Charles, to historians who were eager to preserve the historic waterfront, to tax-conscious citizens who were reluctant to underwrite a $6 million road project, and to Harvard University, which wanted to keep its backyard pristine." Pickets were ready to place themselves in the path of state workers, but they never came. The underpasses never went up.

"It was classic Bernays," says Lerbinger, who has taught at Boston University since 1954 and knew Bernays for 35 years. He recalls Bernays teaching a course at COM in the 1960s entitled Historical Perspectives in Public Relations. "Many of his classes were held at 7 Lowell St., Bernays' large century-old white Victorian," says Lerbinger. "He had many ties to Boston University and was a frequent speaker in classes at COM." In fact, his youngest daughter, Anne, is an adjunct professor in COM's department of journalism. Bernays established the annual Primus Inter Pares Scholarship bearing his name, to recognize the COM student who contributes the most to the field of public relations and to BU's chapter of the Public Relations Society of America.

And, of course, in 1966 BU gave an honorary degree to the "creator of the new profession of public relations and its most distinguished representative, author, teacher, advisor to education, government, and business," as Bernays' citation reads.

A flair for flare

Bernays was an innovator in what he insisted was the "social

science" of influencing public opinion and behavior. What

would the field of public relations be like if Edward

Bernays hadn't existed? "In his day the profession was

already beginning to gel," answers Tye. "There would have

been enough people who would have been seen as its critical

instigators. On the other hand, I would have a hard time

fathoming anyone coming along with as much flair. Somebody

would have done it, but he or she wouldn't have been as much

of a character as Eddie Bernays."