“Provocative, mysterious, touching, baffling, not-to-be-pinned-down, intriguing, and a reminder that genius is free to do as it chooses.”

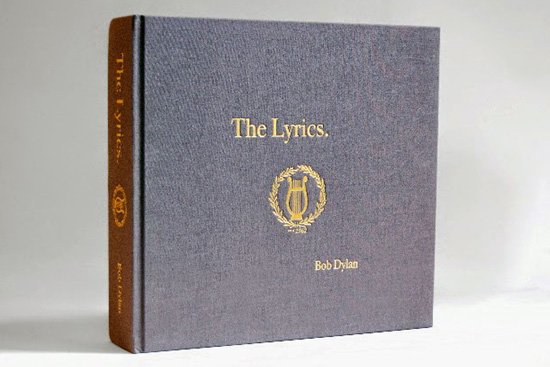

This is how Christopher Ricks characterizes the work of Bob Dylan in his introduction to The Lyrics, a hefty, lavishly produced volume he created with his former student Lisa Nemrow (CAS’87) and her sister Julie Nemrow (CAS’90). Dylan has released 36 studio and 6 live albums since he first knocked the socks off the folk music world in 1962, and his lyrics, which have a way of colonizing entire lobes of the brains of Dylan aficionados, have been collected in bound form before.

But for Ricks, BU’s William M. and Sara B. Warren Professor of the Humanities, who compares Dylan’s cultural influence and likely legacy with that of Shakespeare, the tidily packaged verse in earlier efforts did not reflect the contemporary Bard’s distinctive and inspired phrasing or his penchant for reinventing lyrics when performing the songs live. In fact, as Ricks explains in the introduction to The Lyrics, with all the ink devoted to Dylan over the decades, this is the first time the lyrics are presented as Dylan sang them, with what Ricks calls “very different arcs for each of the songs that he shaped.”

The verses, says Ricks, whose writing on Dylan in his book Dylan’s Visions of Sin (2003, Ecco) was called “the best there is” by New Yorker music critic Alex Ross, “should all be presented to the eye in such a way as to help the eye see what the ear hears.”

“Here are the lyrics, as set down, as sung, and as sung again,” writes Ricks of the collection. With a printing of 3,500 in the United States and 500 in the United Kingdom, at $200 apiece, Simon & Schuster is offering 50 additional copies, at $5,000 each, signed by Dylan. “I didn’t buy one myself,” says Ricks, who met Dylan just once, about 15 years ago at a BU concert “that was a gift to us all from then President Jon Westling (Hon.’03).”

The book was embraced and strongly supported by Simon & Schuster, despite its complicated, expensive production, which required that each book—which is 960 pages, weighs in at 15.2 pounds, and has the dimensions of the reproduced album covers it includes—be assembled by hand.

Ricks has had a decades-long association with the Nemrow sisters, who run Un-Gyve Press, an independent imprint of the Boston-based Un-Gyve Limited Group. Ricks is literary advisor to the small press, which according to its website publishes books of “art, epicurism, literature, history, photography, industry, ephemera, etc.” While not an easy sell, the Dylan book was embraced and strongly supported by Simon & Schuster, despite its complicated, expensive production, which required that each book—which is 960 pages, weighs in at 15.2 pounds, and has the dimensions of the reproduced album covers it includes—be assembled by hand. “As expensive as the main edition was to produce, the limited edition was more so: the gilded edges and slipcase, the paper—made in the United States—and then [Dylan’s] signature, emboss-sealed and certified,” Julie Nemrow says.

“There are a lot of people who believe not only, as I do, that he’s a genius, but believe he is a fascinating and extraordinary genius of a certain kind,” says Ricks. “It was interesting to see Simon & Schuster easily convinced when the Nemrows made the case for the book to be this size.”

Ricks describes their design as inspired and lauds their creation of a format that allowed the three editors to present the lyrics graphically, with the rhymes and emphasis true to the songs as they are heard.

Do the lyrics stand on their own as poetry? Ricks likens the question to asking whether it would be edifying for someone to read only the screenplay of Citizen Kane.

“The words in the movie are terrifically good, but they only constitute part of the art that it is,” he says. “It clearly is an amputation of a song to reduce it to its words. But if the words are really very, very good, then there’s plenty of reward in them. Clearly there are things in Shakespeare that are a combination of what people say with the body language they use—there’s a kind of a vocal body language that you feel.”

Pressing fists to his chest for effect, Ricks cites what he calls “the physical nature” of a verse from “Just Like a Woman”: “your long-time curse hurts, but what’s worse, is this pain in here, I can’t stay in here…”

“Now that’s directly physical writing,” says Ricks.

“We can learn to hear the songs better if we comprehend and apprehend the words more assuredly—or less assuredly when that is the better response,” says Ricks, who explains that one reason the book is so big is that “it’s got lots and lots of full alternative versions of a song.”

And with Dylan, a song may be altered with different instrumentation or different words during its long life, to the point where it is less a version of a song than a new song. Dylan likes to change the order of his stanzas or play with pronouns, as in the “Tangled Up in Blue” line that morphs from “I was laying in bed” to “he was laying in bed,” Ricks explains.

Dylan and his agents approved both the text and the design of the book, and offered any material or information that Ricks and the Nemrows needed to get it right, they say.

Beyond a reverence for Dylan, the book reflects a partnership born at BU, and a shared commitment to timeless words and craftsmanship.

As Ricks puts it, the only thing predictable about Un-Gyve is that it’s unpredictable. “But, our books are, predictably, always made of paper and ink. We’re traditionalists,” Lisa Nemrow says. “Our effort is to ensure that books that are supposed to be made are made and get made in the right way.”

My copy arrives this or next week. No matter what any other artist creates, this will remain the most important book I own and will become an heirloom for the generations that come after me. When people say, “Bob is like Shakespeare,” they are still grasping at straws, still slightly amputated in perception by trying to perceive Dylan through comparison. He is unique, and unless one comprehends exactly what ‘unique’ means, one cannot begin to approach Dylan in full light. The harp illustration on the cover says what every word in the book cannot. ‘You are beautiful beyond words’. Angel in the night with ragged lyrical torchlight for the ones to tired to see with sight. Thank you Bob Dylan.

Thank you Christopher Ricks and compadres. ‘I love you more than ever, more than time, more than love’…for creating this for those of us.

Brilliant work all around. I will never forget hearing “It’s Alright Ma” for the first time, and being knocked out by each brilliant, cascading verse.