BU’s Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center (HGARC) traces its modest origins to a man at a desk in the University’s pre–Mugar Memorial Library Chenery Library at the School of Theology. That man was archivist Howard Gotlieb (Hon.’88), the year was 1963, and what landed on his desk was the first of an extensive collection of personal papers of the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. (GRS’55, Hon. ’59), who donated 83,000 documents to BU before his assassination in 1968. Thousands more would follow. A half-century, nearly 2,000 individual archives, an exhibition space, and a sprawling office suite later, the center is a leading trove of contemporary culture, with an estimated nine miles of shelves of correspondence, photographs, manuscripts, and priceless ephemera of luminaries from Bette Davis to David Halberstam to Kate Smith. “Our mission is to capture history and preserve it,” says director Vita Paladino (MET’79, SSW’93).

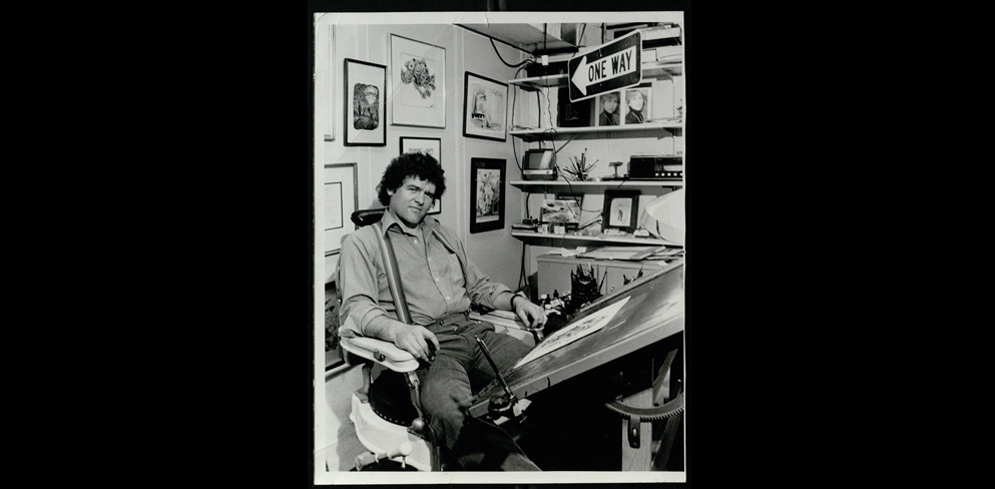

Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center director Vita Paladino (MET’79, SSW’93) has continued in founder Gotlieb’s tradition of landing new collections using perseverance and charm.

The center has been based on the fifth floor of Mugar Memorial Library since 1966, when the University gave Gotlieb another reference librarian, a secretary, and a space that would multiply as the collection and staff grew. Then known as Special Collections, it was renamed the Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center on its 40th anniversary in October 2003. Over the years, Gotlieb honed his reputation as a tireless letter writer and host who “cajoled, charmed, wheedled, and—most effectively, he said—groveled to snare the papers of notables,” wrote Douglas Martin in Gotlieb’s December 5, 2005, New York Times obituary.

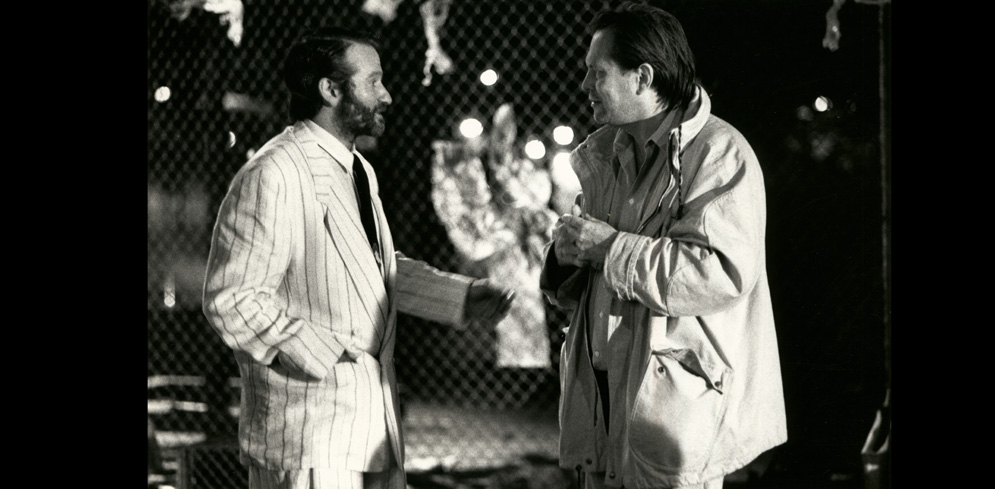

In the center’s fledgling years, the only other archive doing something similar was the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin, says Paladino. With her winning, outsized personality and her gift for schmoozing, she is a fitting successor to Gotlieb, who was her mentor and friend. She has been at the center for 37 years, although, she asserts with characteristic Dorothy Parker wit, she is only 34. Over the years her connections continue to spawn more connections—satisfied customers such as Terry Gilliam introduce her to friends, like Robin Williams—and now, like her predecessor, Paladino is on the invite list of many a star-studded event. She loves it.

A big part of Gotlieb’s success early on was because “the fact was, nobody else was asking, and he was very charming,” she says. She recalls the Oscar-winning actress Joan Fontaine remarking that Gotlieb won her over with the promise that her sister, Olivia de Havilland (another Oscar winner), with whom she has famously feuded her entire adult life, would never see Fontaine’s papers. Gotlieb “stopped at virtually nothing to capture his prey,” Martin wrote. He wooed potential donors with flowers and gifts, including, according to the obit, a bed for actor James Mason.

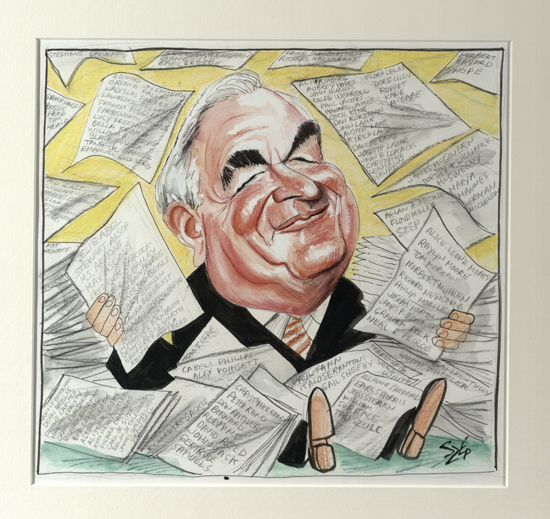

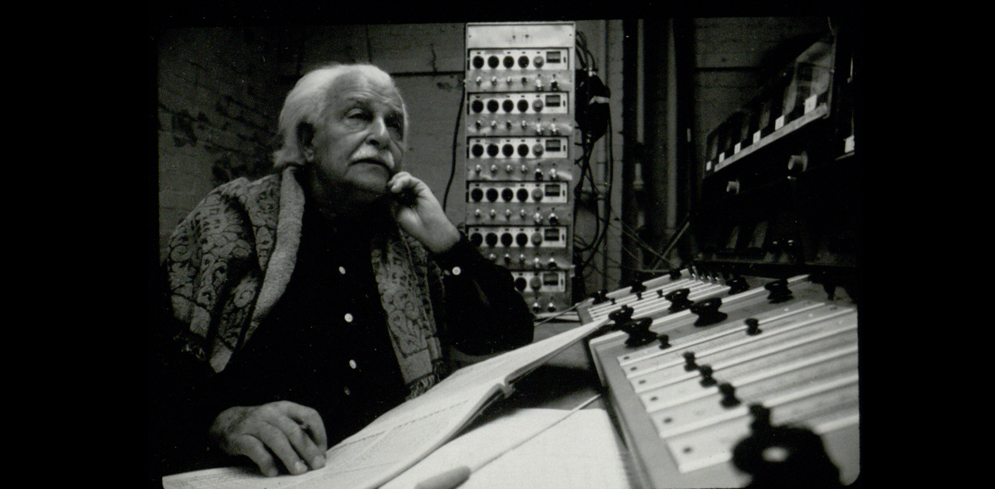

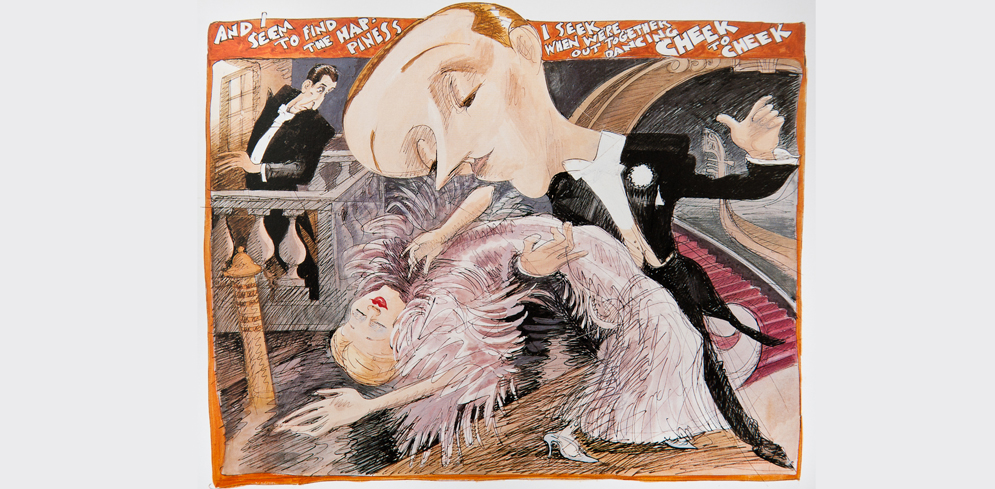

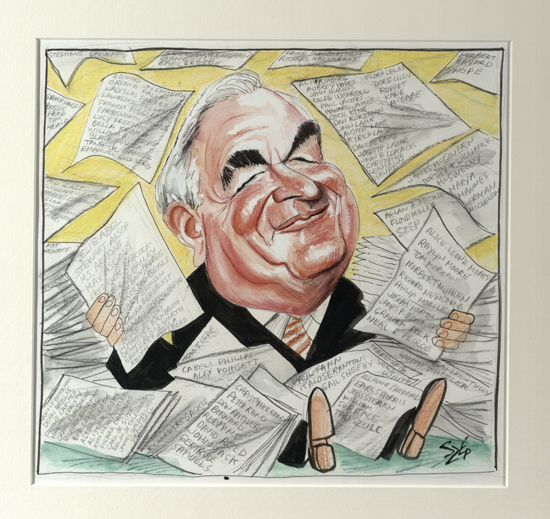

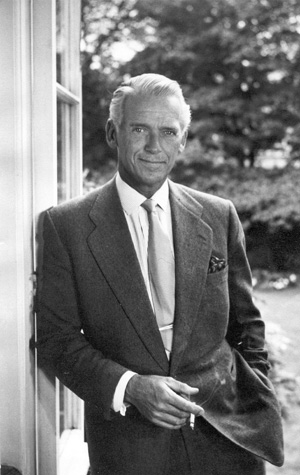

Howard Gotlieb (Hon.’88) as depicted by two-time Pulitzer-winning former Boston Globe editorial cartoonist Paul Szep, whose collection is at the Gotlieb Center.

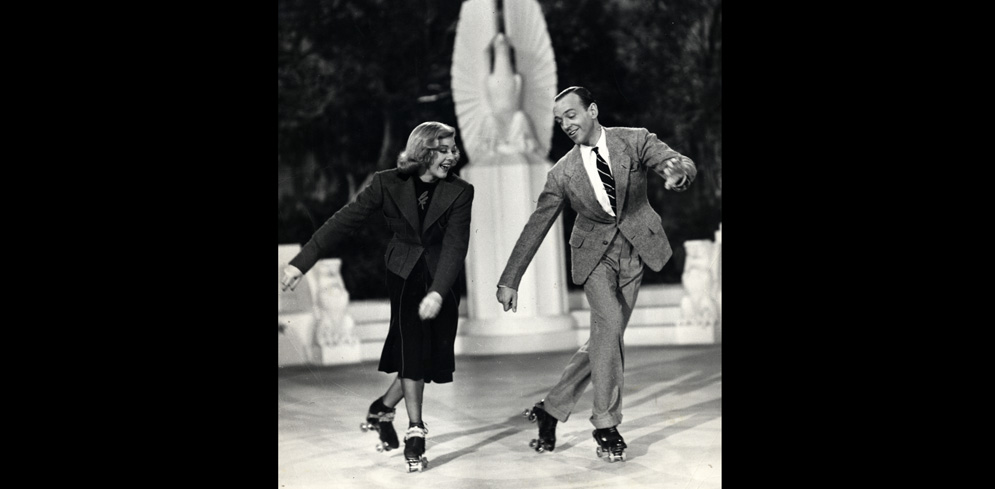

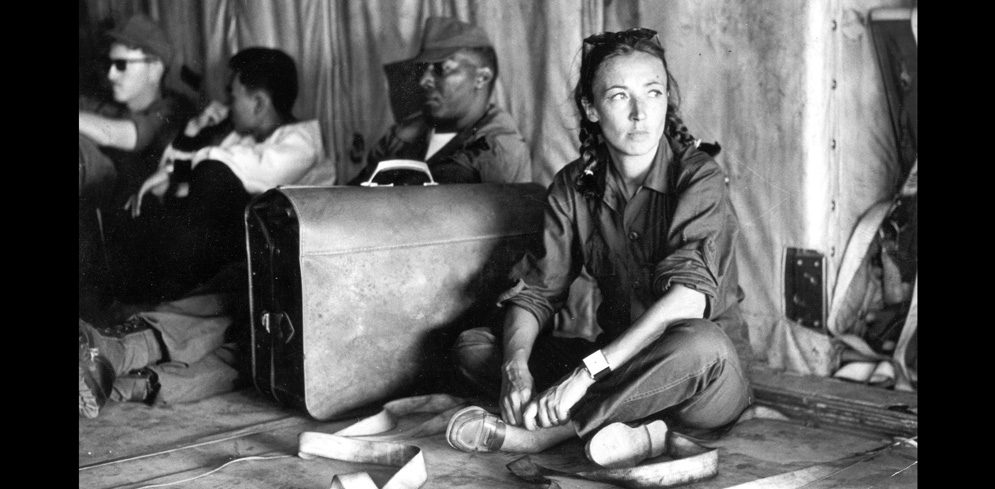

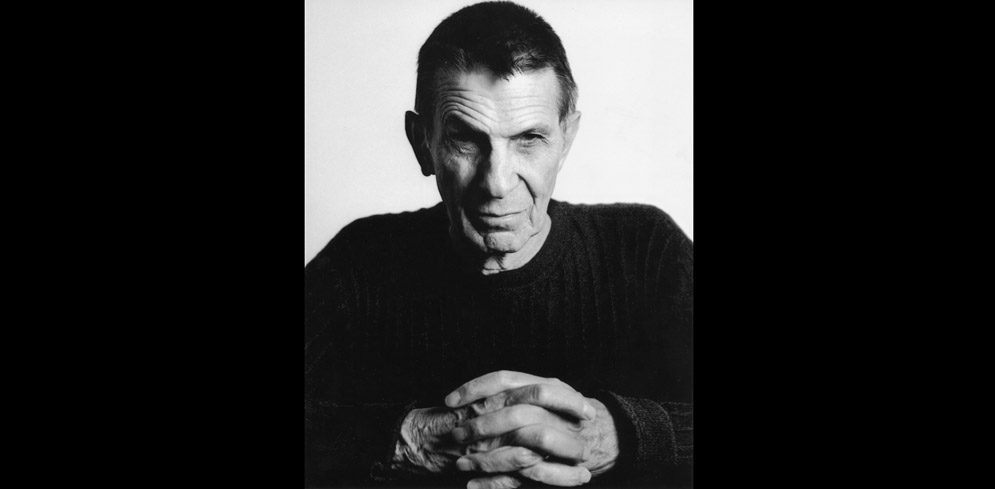

Asking the center’s staff which collections are their favorites is like asking, “which child do you love most?” says associate director Sean Noel. Noel and Paladino acknowledge that there are some standouts: President Richard Nixon’s letter of resignation, Fred Astaire’s tap shoes, and a recent acquisition, original drawings by cartoonist and illustrator Edward Sorel. The HGARC has become internationally renowned for its collections from the fields of literature, criticism, poetry, dance, music, theater, film, television, political and religious movements, and especially journalism, which Paladino is particularly passionate about. “Journalists are seekers of truth, and they create a paper trail,” she says, citing invaluable historical records such as field notes from the likes of war correspondents Martha Gellhorn, Frances FitzGerald, Gloria Emerson, Philip Caputo, and Carleton Beals. Unlike its counterpart, the Ransom archive in Austin, which several years ago purchased Norman Mailer’s papers for $2.5 million, the Gotlieb Center has a small budget, and nearly 95 percent of its collection is donated, says Paladino, who might rein in a donor, like Gilliam, with a personal pitch or woo potential donors with a tour of the archive, like actors Jane Alexander, Ben Vereen, and Leonard Nimoy (Hon.’12). Gilliam, a former Monty Python member, writer, and animator, who directed Time Bandits and 12 Monkeys, and his wife invited Paladino to their “magical” home, which was decorated with props from his many films, she says.

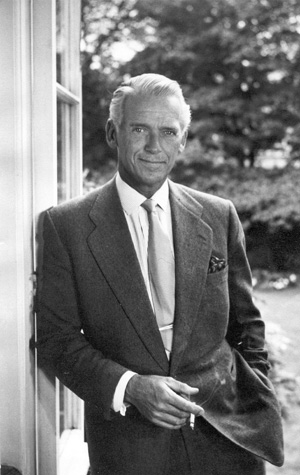

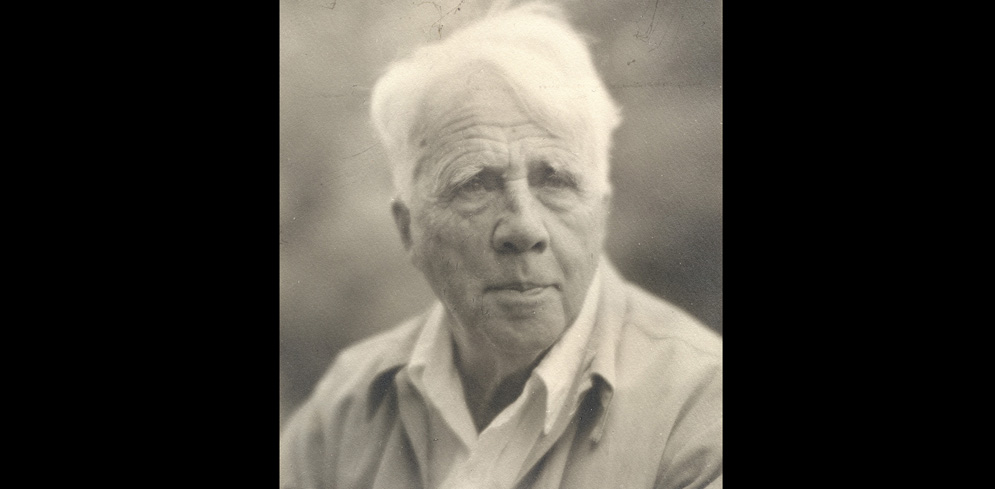

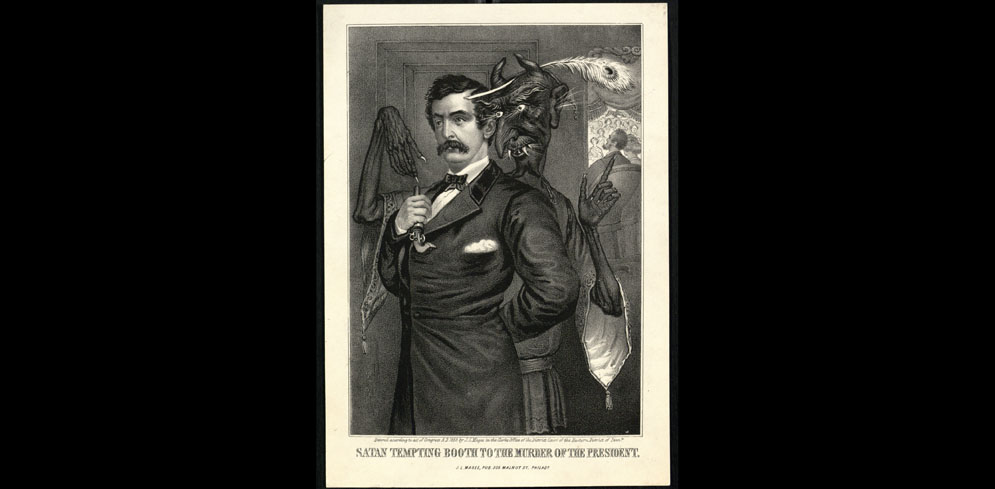

Gotlieb reportedly had to pry a set of diaries from the hands of archive donor and famed actor Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.

“My competitor hunts with a machine gun; I have to go with a bow and arrow,” says Paladino, who keeps in touch with donors through Christmas and birthday cards and attends their performances and receptions. When the late Italian journalist and author Oriana Fallaci came to Boston for cancer treatments, Paladino accompanied her to the hospital. Her connection to the collectees is, by definition, personal. “That’s why I have a master’s in social work,” says Paladino. “You want to hear their stories, the private lives, the behind-the-scenes side to their lives. You need to build trust.” Paladino counts Angela Lansbury and Lauren Bacall among her good friends and has a Rolodex full of the cell phone numbers of A-listers. She understands how it can be difficult for people to part with their papers while they’re still alive. Gotlieb himself had to practically pry a set of leather-bound diaries from the hands of Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., although the actor had agreed to donate them.

During Paladino’s watch the center has added rotating exhibitions, seminars, community tours as well as tours for incoming freshmen and their parents, educational outreach programs, and collaborative digital archives. The Friends of HGARC host readings, timely panel discussions, and speakers who in the last few years have included journalist Pete Hamill, author Walter Moseley, and Irish tenor Ronan Tynan. A staff of 20 handles the never-ending work of sorting, cataloging, and preserving documents and making them available to researchers and biographers from all over the world. Paladino has played a role in pairing collectees with biographers, most recently Tina Sutton, author of The Making of Markova, a critically acclaimed biography of legendary prima ballerina Dame Alicia Markova, whose archive is at HGARC.

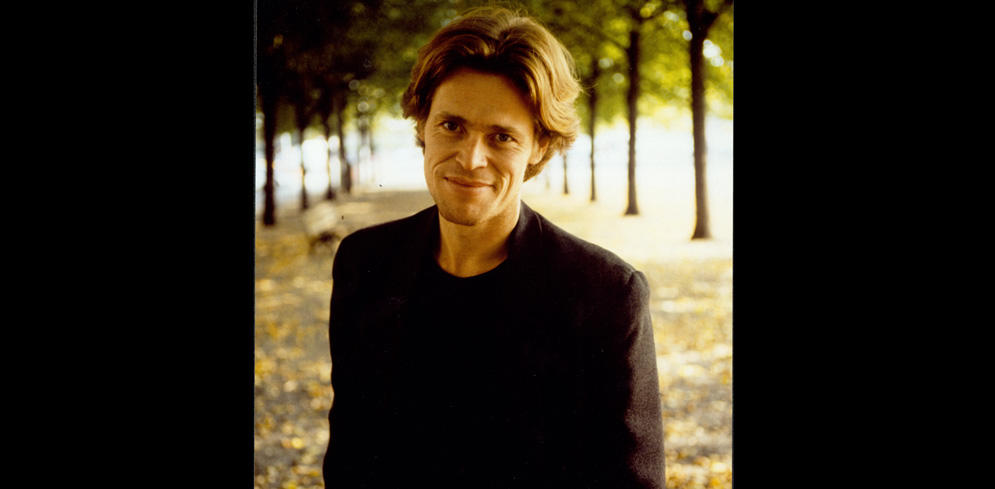

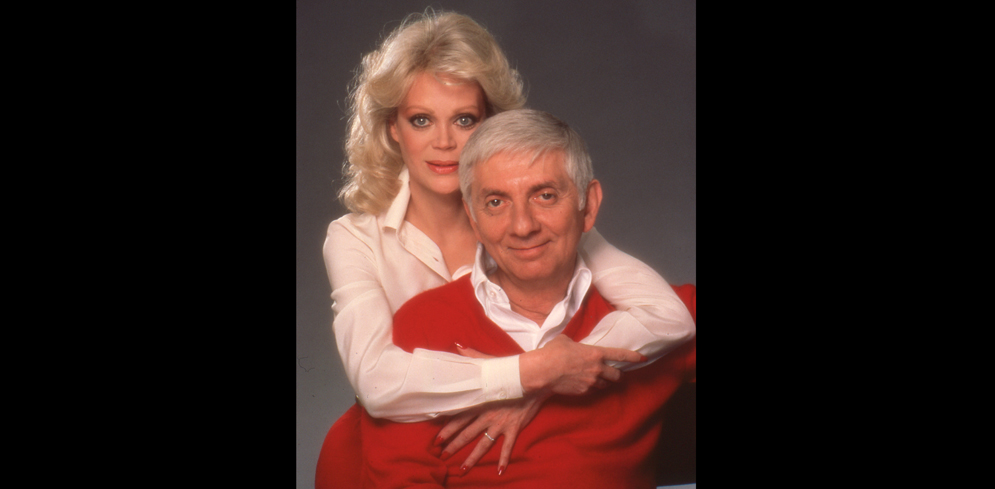

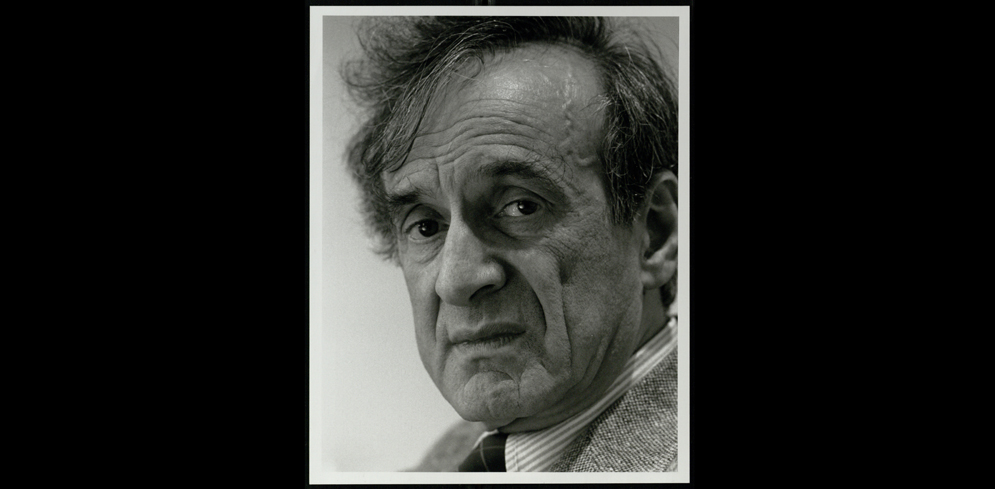

Internationally known for interviews with figures like Ayatollah Khomeini and the Shah of Iran, the late Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci grew close to Paladino after donating her papers to the center.

“Vita’s always pursuing new people, but she’s got to maintain relationships,” says Noel. “You get new information all the time.” The center receives 10 to 50 boxes a week that must be processed, and after donors’ deaths more material flows in from their heirs, families, and literary executors. The boxes may hold the carefully cataloged correspondence and keepsakes of a lifelong obsessive (Fred Astaire kept meticulous scrapbooks), or they can overflow with hastily thrown-together flotsam. “We’re the professionals who can screen things and put aside what isn’t of research value,” says Paladino. “We can say, ‘We don’t need your divorce papers.’” Archivists have stumbled on pornography and a sizable, never-cashed check. “Here we get the narratives of people’s lives,” she says. “Do I know a lot of secrets? Yes.”

Intended for use by scholars, not fans (that’s what the exhibitions are for, says Noel) HGARC arranges for researchers to examine collections in a quiet, well-appointed reading room monitored by closed-circuit cameras. Laptops, pencil, and paper are permitted, but coats, purses, and phones must be left at the desk. “No one is ever really alone with the collections,” Noel says. “We have a very set protocol, and we’ve never had any problems.”

Paper collections–memorabilia people can hold and touch—are destined to dwindle as email replaces the elegantly dashed-off note or the transatlantic telegram. But Paladino sees the change as opening the door to a new, more accessible type of archive. “We’ll have better record-keeping electronically, and paper takes up space, which somebody has to pay for,” she says. “You’ll have electronic archives and people all over the world will have access to them; that’s not a bad thing.”

Related Stories

Mugar Exhibits Gotlieb Center’s Elie Wiesel Archive

Letters, manuscripts, photos, Nobel Prize on display

Gotlieb Center’s Aaron Spelling Exhibition at Mugar

Scholarship fund named for prolific TV producer part of Century Challenge

MLK on Display at BU’s Gotlieb Center

Nobel laureate gave his papers, other items to his alma mater in 1964

Post Your Comment