Corporate Social Responsibility during Covid-19: The Clean Zone Initiative in South Korea

By Hyejin Yoon, Assistant Professor, Baewha Women’s University, Changsik Kim, Ph.D., Baewha Women’s University, and Sunny Ham, Professor, Yonsei University

Introduction

The novel coronavirus (hereafter Covid-19), first and foremost, has caused an unprecedented global catastrophe. Global tourism faced its worst year in 2020, with international arrivals falling by 74% (UNWTO, 2021) to 80% (OECD, 2020), according to the worldwide tourism data. Hospitality businesses and MICE (Meeting, Incentive tour, Convention, Exhibition and events) have been particularly struggling because these sectors rely greatly on international tourism demand. The hospitality industry is a vital part of a growing services economy and the world’s most important sectors creating income, jobs, foreign exchange, and supporting local communities and developments (OECD, 2020). The sector directly contributed approximately 4.4% of GDP, 6.9% of employment, and 21.5% of service exports in OECD member countries in 2018 (OECD, 2020).

Unfortunately, the Covid-19 pandemic has hit the hotel sector hard, with unexpected effects on jobs and businesses caused by low occupancy and high overhead. Many hotel businesses have been forced to temporarily close, often falling into permanent closure due to the government policies and rules that restrict business activities to reduce virus infection (e.g., travel restrictions, social distancing rule, and staying-at-home orders) across the globe. For instance, the number of tourist hotels in Seoul, the capital city of South Korea, declined for the first time due to the Covid-19 pandemic since records began in 2008, according to the Ministry of Culture, Sport, and Tourism (MCST). As a result, during 2020, the number of the five-star, four-star, three-star, and two-star hotels decreased by one, six, fourteen, and seven hotels, respectively. For example, in 2021, the five-star luxury hotels – Sheraton Seoul Palace Gangnam Hotel, Le Meridien Hotel, and Millennium Hilton Seoul, which boasted a history of 38 years – were closed because of their vast fixed costs (MCST, 2021).

Due to the evolving nature of Covid-19, many governments are still keeping travel restrictions and social distancing policies in place, and customers are worried about visiting public spaces, including hotels and restaurants. At the same time, a recent novel Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) activity, such as Clean Zone practices in hotels, is expected to help consumers feel safe and restore consumer confidence amid the Covid-19 anxiety. He and Harris (2020) also suggest that the pandemic offers a variety of meaningful opportunities to those businesses with a more insightful approach to CSR, particularly helpful to the fight against the Covid-19 virus for companies, suggesting that their efforts in fighting the virus can build a stronger rapport among their consumers during the crisis. In this context, many hotels in South Korea have participated in the activity called “Clean Zone” certification which establishes guidelines of a hygiene and disinfection standard (e.g., measuring body temperature, wearing a mask, cleaning hands, operating a Clean Zone, physical distancing, cleaning, and disinfecting, Choi, 2020; Park, 2020).

Several major metropolitan cities in South Korea, such as Seoul, Busan, and Incheon, have launched the Clean Zone program and provided the Clean Zone sticker (see Figure 1). Through the certification, participants receive a sticker to indicate that their property gets disinfected on a regular basis based on the authority’s guidelines (Seoul, 2020). Numerous hotels have conducted required disinfection practices to acquire a “Clean Zone” certificate and promoted this certification to hotel guests displaying this mark both inside and outside (see Figure 2). The participating hotels disinfect all reserved rooms and put a Clean Zone sticker that reads “Disinfected Room” on the door to help guests feel safe and comfortable. In addition, several hotels have started the promotion of “Kids Safety Clean Zone.” It provides an expensive nano-drone air purifier (approximately USD 5,500), which eliminates ultra-fine dust, harmful viruses, and bacteria (Yoo, 2020). These activities greatly help satisfy consumers’ higher expectations for safety and hygiene during the pandemic for the Korean hotel industry (Yoo, 2020).

Figure 1. The Clean Zone certification and its use in hotels. Source 1: Seoul metropolitan government (http://english.seoul.go.kr/seoul-attaches-clean-zone-stickers-on-facilities-that-can-be-used-without-worry-about-infection/). Source 2: Cocomo hotel

Figure 2. The Clean Zone marketing and promotion. Source: booking.com

Similar to the Clean Zone certificate implemented in South Korea, several other countries (e.g., Portugal, Switzerland, Singapore, and Malaysia) have launched a campaign where tourism destinations, including hotels can become certified as clean and safe places that meet several requirements including frequent disinfection activities, and monitoring the health and practices of employees (Figure 3). Also, some hotel corporations started their own clean programs. For example, Marriott International has launched a global cleanliness council to promote its standards for cleanliness and other practices to meet the new safety and health expectations (Bohm & Miktus, 2020).

Figure 3. Clean and Safe certification worldwide. Source: Portugal on the left (portugalcleanandsafe.com), Switzerland in the middle (myswitzerland.com), Singapore on the right (sgclean.gov.sg)

These certificate programs not only encourage the hotel industry to be more socially responsible, but also to satisfy their consumers’ expectations. However, little is known about consumers’ perceptions and attitudes on hotels’ current adoption and efforts of the Clean Zone certification, as well as how effective they are. Therefore, this article aims to understand such perceptions.

Survey

The self-administered survey questionnaire was used to first ask respondents for their knowledge about the Clean Zone. Afterwards, the survey provides a description of the Clean Zone, which is then followed by questions about participants’ perceptions about the Clean Zone and their demographic information: age, gender, education, marital, household income, number of children, and the star rating of the hotel that they most frequently visit. Well-established multiple-items with 5-point or 7-point Likert scales, ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5 or 7), are the adopted measures for the study variables except for demographic information. The data was collected from December 4, 2020 to January 13, 2021 in Korea. The questionnaire was distributed using a web-based survey system by a research company. A quota sampling method, based on the hotels’ census figures of the Korean population, was the basis for selecting the participants in the study. The quota sampling procedure applied to age and gender as the primary control characteristics.

Results

Sample profile

The sample profile is presented in Table 1. Among 215 respondents, 47.9% were female, and 52.1% were male. The age distribution includes the two largest groups of 50-59 years (30.2%) and 40-49 years (26.0%), while 23.7% and 20% belong to the age group of 30-39 years and 20-29 years, respectively. About 60% of the respondents were married in terms of marital status, whereas 38.1% were single. Regarding education levels, 73.0% held bachelor’s degrees, and about 15% held graduate degrees, while about 12% of the respondents were high school graduates. In terms of yearly household income before taxes, the largest group earned above $66,000 (34.0%), followed by $44,000-$65,999 (26.5%), $30,000-$43,999 (25.1%), and under $29,999 (14.4%). Approximately half of the respondents have children. With respect to the hotel star-rating frequencies, about 40% of the respondents visit 4-star the most, followed by 3-star (31.2%), 1 or 2-star (15.3%), and 5-star (14.0%), respectively.

Table 1. Sample Profile

| Variables | Number | % | Variables | Number | % | ||

| Gender | Male | 112 | 52.1% | Marital | single | 87 | 40.5% |

| Female | 103 | 47.9% | married | 128 | 59.5% | ||

| education | high school | 26 | 12.1% | Age | 20-29 | 43 | 20.0% |

| bachelor | 157 | 73.0% | 30-39 | 51 | 23.7% | ||

| graduate | 32 | 14.9% | 40-49 | 56 | 26.0% | ||

| children | have | 111 | 51.6% | 50-59 | 65 | 30.2% | |

| do not have | 104 | 48.4% | Frequently used hotel | below

3-star |

33 | 15.3% | |

| household annual income | 21,000-29,999 | 31 | 14.4% | 3-star | 67 | 31.2% | |

| 30,000-43,999 | 54 | 25.1% | 4-star | 85 | 39.5% | ||

| 44,000-65,999 | 57 | 26.5% | 5star | 30 | 14.0% | ||

| 66,000- | 73 | 34.0% | Total | 215 | 100% | ||

Main results

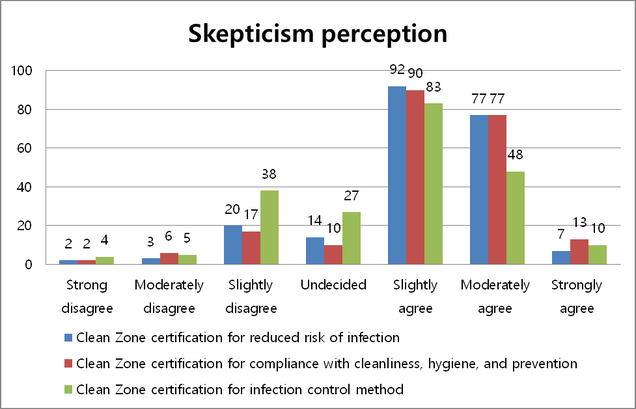

This study conducted a descriptive analysis about consumer’s perception (skepticism and clean zone) of hotels. As a result, most respondents significantly agreed on the impact of Clean Zone certification on consumers’ skepticism perception (Table 2 and Figure 4).

Table 2. Results of consumers’ perceptions about the Clean Zone

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | Total | |

| It is certain that this certificate is concerned to protect the risk of coronavirus infection | Number | 2 | 3 | 20 | 14 | 92 | 77 | 7 | 215 |

| % | 0.9% | 1.4% | 9.3% | 6.5% | 42.8% | 35.8% | 3.3% | 100 | |

| It is sure that this certificate follows high standards of cleaning and hygiene | Number | 2 | 6 | 17 | 10 | 90 | 77 | 13 | 215 |

| % | 0.9% | 2.8% | 7.9% | 4.7% | 41.9% | 35.8% | 6.0% | 100 | |

| It is unquestionable that this certificate acts in a good infection-controlling way | Number | 4 | 5 | 38 | 27 | 83 | 48 | 10 | 215 |

| % | 1.9% | 2.3% | 17.7% | 12.6% | 38.6% | 22.3% | 4.7% | 100 | |

Note: (1) Strongly disagree (2) Moderately disagree (3) Slightly disagree (4) Undecided (5) Slightly agree (6) Moderately agree (7) Strongly agree

Figure 4. Visualization on Consumers’ Perceptions about the Clean Zone

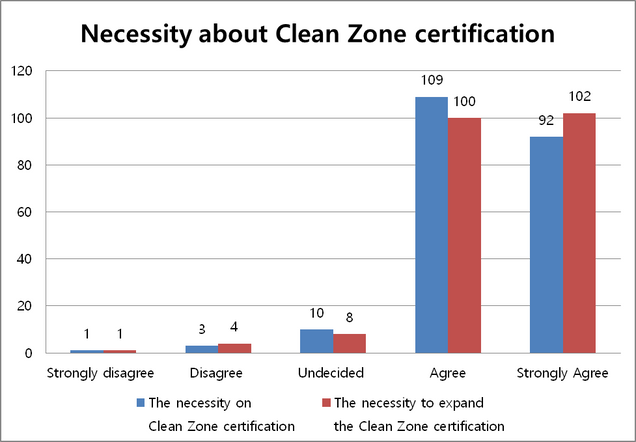

Also, most respondents clearly agreed on the need and expansion of the Clean Zone certification as shown in Table 3 and Figure 5.

Table 3. Results of Need and Expansion of the Clean Zone certification

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | Total | |

| The necessity on Clean Zone certification | Number | 1 | 3 | 10 | 109 | 92 | 215 |

| % | 0.5% | 1.4% | 4.7% | 50.7% | 42.8% | 100% | |

| The necessity to expand Clean Zone certification | Number | 1 | 4 | 8 | 100 | 102 | 215 |

| % | 0.5% | 1.9% | 3.7% | 46.5% | 47.4% | 100% | |

Note: (1) Strongly disagree (2) Disagree (3) Undecided (4) Agree (5) Strongly Agree

Figure 5. Visualization on the Necessity of Clean Zone Certification

This study further compared some groups regarding their perceptions about the Clean Zone certification, using means analysis (e.g., t-test, ANOVA) on the following characteristics: gender, marital status, and the hotel star-rating they visit the most. First, when we compared customers’ perceptions about the effect of the Clean Zone certification between males and females, our analysis shows no significant difference. Next, we compared customers’ perceptions between the married and unmarried, and our results present that the married group believes more strongly about the positive effect of the Clean Zone certification than the unmarried group for two questions: “It is certain that this certificate is concerned to protect the risk of coronavirus infection” and “It is unquestionable that this certificate acts in a good infection-controlling way.” We then compared customers’ perceptions between the group with and without children in their household, and our results show that the group with children clearly demonstrates more positive perceptions about the effect of the Clean Zone certification for several questions: “It is certain that this certificate is concerned to protect the risk of coronavirus infection,” “It is unquestionable that this certificate acts in a good infection-controlling way,” “The necessity on Clean Zone certification,” and “The necessity to expand Clean Zone certification.”

Conclusion and Practical Implications

Findings of this study, in general, support the positive effectiveness of the Clean and Safe certificate implemented in many countries. The Clean Zone certification adopted in South Korea appears to play a vital role in improving hotel customers’ perceptions about the effectiveness of hotels’ cleaning practices, thus enhancing their confidence about staying in a hotel. Our findings provide some implications for the hotel industry. First, hotel operators are strongly encouraged to consider implementing an official certificate regarding cleaning and disinfection activities as part of their CSR strategy. When they engage in such a program, hotel operators should also consider clearly making evidence of the certification visually available to their customers so that the customers can clearly see it, thus be well informed of the practice of the hotel’s efforts of combating coronavirus. Second, hotels may consider putting in more efforts to assure the confidence of particular groups of their guests, such as married couples and families who have a child/children, by establishing and reinforcing clean activities through adopting an official certificate, physical evidence, and a marketing campaign. Hotel operators should also be aware that there is no gender difference in customer’s perceptions about the effectiveness of the clean-related certificate. As a result, the hotels may continuously develop, operate, and update a clean and hygiene program and plan even after the Covid-19 pandemic. Such high-standard ethics and practices should be physically and diligently delivered and further informed (online and offline) to all current and potential customers so that they will feel safe and comfortable with their decision to stay at a hotel.

While this paper found that the positive impact of the Clean Zone certification on hotel customers’ perceptions and attitudes may lower levels of health risks, hotels require a certain level of capital investment in CSR practices (i.e., the Clean Zone certificate, González-Rodríguez, Díaz-Fernández, & Font, 2020; Millar & Baloglu, 2011). As a result, they may need to increase their average daily rate to make up for their investment. Therefore, further investigation is needed to examine customers’ willingness to pay premium prices for Clean Zone certified hotels. Also, future research needs to expand the topic in the contexts of individual or branded hotels, leisure or business travelers, and different cultural backgrounds of hotel customers.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Mr. Jihwan Yeon and the guest editors for their constructive comments

References

43 comments

SexyPG888 เว็บเดิมพันออนไลน์ บาคาร่า ออนไลน์ ที่นักเดิมพันนิยมเล่นเป็นอันดับ 1 ของประเทศไทย เว็บตรง ที่ดีที่สุดในตอนนี้

Impressive Content.Power BI TrainingReally appriciated

I really appreciate the information and advice you have shared with us. Many thanks for sharing this useful and valuable information.

H‑E‑B Partner Services

Thanks for the information.. smiONE

very nice information you have shared here.

C4Yourself

I know you will need the information from the above article, but you should learn more run 3 it’s a pretty cool game genre these days!

Wilson Jackets Cotton Jackets Collection offers a selection of stylish jackets that can be worn alone or pair with other outfits for a more eye-catching look

คาสิโนออนไลน์ใหม่ ที่มั่นคงปลอดภัย เปิดโอกาสให้ผู้เล่นเข้ามาร่วมวางเดิมพันได้หลากหลายรูปแบบด้วยกัน ไม่ว่าจะเป็นบาคาร่า เสือมังกร ไฮโล รูเล็ต น้ำเต้าปูปลา ถ่ายทอดสด ส่งตรงจากคาสิโนจริง

has to say that it is the most popular classic right now with online slot games. Which has more than 50 forms for members to choose from and many game rooms, the best automatic deposit and withdrawal, has a standard deposit and withdrawal system, is a quality direct website slot that you definitely can’t overlook888xbets

I will always let you and your words become part of my day because you never know how much you make my day happier and more complete. There are even times when I feel so down but I will feel better i need an assignment right after checking your blogs. You have made me feel so good about myself all the time and please know that I do appreciate everything that you have

very nice information you have shared here.

Caregiver Connect

Do you need accounting assignment help? If so, then I can help! I am an experienced accounting assignment helper with over 5 years of experience. We are providing accounting assignment helper for the students looking for an accounting assignment helper who is experienced, knowledgeable, and results-oriented.

Introducing SMM Panel India, your gateway to unlocking the immense potential of social media marketing in the Indian market. With our panel, tailored specifically for India, you can harness the power of social media to reach a vast audience, build your brand, and drive meaningful engagement. Our services include likes, followers, comments, and more, all carefully crafted to cater to the unique needs of businesses and influencers in India.

MyKohlscard is an incredibly useful tool for shopping at the store and online. It gives me access to exclusive deals, coupons, and rewards points that can be used towards future purchases. I can also easily track my spending and keep a record of all my past purchases on mykohlscard. I love using my Kohls card because it makes shopping more convenient, rewarding, and stress-free.

As technology continues to shape the world of timekeeping, Apple Watch and Fitbit Watch have emerged as trailblazers in the smartwatch category. The Apple Watch for sale is renowned for its seamless integration with iOS devices and an extensive range of features to enhance your daily life.

Breitling Navitimer is an iconic collection that has been a favorite among pilots and aviation enthusiasts for decades. With its distinctive circular slide rule and chronograph functions, the Navitimer is a true instrument for professionals.

I really amazed to read this blog post. It is so unique and informative Shearling and Fur Coats

Thanks for share this to us !!! paybyplatema

Thanks for sharing this best stuff with us! Keep sharing! I am new to blog writing on Mulesoft Training All types of blogs and posts are helpful for the readers.

Very interesting blog. Thanks for sharing your experience. Caregiver Connect Aurora

Salutari tuturor. Sunt un participant activ la acest subiect și vă citesc frecvent scrierile. Accesați și această pagină web.

https://menuromania.com/taverna-racilor-meniu/

Caregiver Connect is an extensive platform that recognizes the particular requirements and challenges that caregivers experience in various circumstances. Caregiver Connect Aurora

It is such an informative post and helps me a lot. Currently I am working on trubridgepaystubs, you can also visit page

Greetings to all of you. I read your work frequently and take an active interest in this topic. View this webpage as well.

receptify

Drift Hunters is a great drift racing game, with beautiful graphics, exciting gameplay, and a vibrant gaming community. If you love drift driving and want to challenge your skills, this game is a great choice.

In an era where health and wellness take center stage, Apple Fitness emerges as a transformative force, seamlessly integrating cutting-edge technology with fitness routines. This article explores the impact of Apple Fitness on our pursuit of a healthier lifestyle.

The Evolution of Apple Watch Series:

Before delving into the fitness realm, it’s crucial to acknowledge the evolution of Apple’s smartwatches. From the groundbreaking Apple Watch Series 5 to the recently unveiled Apple Watch Series 9, each iteration represents a step forward in design, functionality, and overall user experience.

In the world of horology, the Omega Seamaster Watches Midsize stands as a testament to precision, craftsmanship, and enduring style. This article delves into the distinctive features that make this timepiece a favorite among watch enthusiasts.

Omega Watches for Men: Crafting Elegance:

Explore the world of Omega Watches for men, where every timepiece is a masterpiece of design and engineering. The Seamaster Midsize, as part of this illustrious collection, embodies the brand’s commitment to creating watches that go beyond mere timekeeping.

Citizen Eco Drive: A Fusion of Technology and Elegance:

Among the esteemed brands in the world of mens diamond watches is Citizen Eco Drive. Known for its innovative solar-powered technology, Citizen seamlessly integrates functionality with elegance. The inclusion of diamonds on selected models adds a touch of luxury, creating timepieces that transcend conventional expectations.

First off, kudos on shedding light on a lesser-known hero of the pandemic – the corporate sector with a conscience. The way you unfolded the journey of businesses rallying to create a safer environment, not just for their workforce but the community at large, was downright inspiring.

https://www.amazonprimeparty.com/

Brolly Academy offers a wide range of trending IT courses designed to provide students with valuable skills and 100% placement assistance. Here are 50 trending IT courses that you can explore at Brolly Academy

https://brollyacademy.com/mulesoft-training-in-hyderabad/

we offers a wide range of trending IT courses designed to provide students with valuable skills and 100% placement assistance. Here are 50 trending IT courses that you can explore at Mule Masters

https://mulemasters.in/snowflake-training-in-hyderabad/

nice article.

thanks for sharing with us

SEO Institute In Hyderabad

Exciting News: Brolly AI now offers a cutting-edge course in Prompt Engineering! Unlock the secrets of crafting powerful prompts to maximize your AI interactions. Elevate your skills and stay ahead in the world of artificial intelligence with Brolly AI’s expert-led training. Enroll today: [Course Link] #AI #PromptEngineering #BrollyAICourse

Prompt Engineering Course in Hyderabad

Unfortunately, the Covid-19 pandemic has hit the hotel sector hard, with unexpected effects on jobs and businesses caused by low occupancy and high overhead. Many hotel businesses have been forced to temporarily close, often falling into permanent closure due to the government policies, but now they are moving toward betterment, so hopefully industry will grow soon. Medical Billing Services in San Antonio, TX

The advantages of EHall Pass is an option in contrast to the paper identification. It permits you to make a computerized ID card when required and your instructor can enter or click a pin on the site to initiate it. EHallPass Login

Title: Unveiling the Power of Snowflake: Revolutionizing Data Warehousing in the Digital Era

In the fast-paced world of data management and analytics, businesses are constantly seeking innovative solutions to harness the power of their data effectively. Snowflake emerges as a transformative force in this landscape, offering a cloud-based data warehousing platform that redefines scalability, flexibility, and performance. With over a decade of experience in SEO content writing, I delve deep into the realm of Snowflake, elucidating its key features, benefits, and the unparalleled opportunities it presents for businesses worldwide.

Understanding Snowflake: A Paradigm Shift in Data Warehousing

Snowflake stands as a beacon of innovation in the realm of data warehousing, offering a cloud-native platform that transcends the limitations of traditional solutions. At its core, Snowflake is built upon a unique architecture that separates compute, storage, and query processing, enabling unparalleled scalability, concurrency, and performance.

Key Features and Capabilities

Multi-cluster Architecture: Snowflake’s multi-cluster architecture allows for seamless scaling of compute resources based on workload demands, ensuring optimal performance and cost efficiency.

Automatic Scaling and Concurrency: With Snowflake’s automatic scaling capabilities, businesses can handle fluctuating workloads effortlessly, while built-in concurrency controls ensure fair resource allocation and efficient query processing.

Data Sharing and Collaboration: Snowflake facilitates seamless data sharing and collaboration across organizations, enabling secure sharing of data sets and insights with internal teams, partners, and customers.

Advanced Analytics and Insights: Leveraging Snowflake’s integrated analytics capabilities, businesses can derive actionable insights from their data through advanced analytics, machine learning, and data visualization tools.

Security and Compliance: Snowflake prioritizes security and compliance, offering robust encryption, access controls, and auditing features to ensure the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of data.

Snowflake Course in Hyderabad

He remains upbeat and loyal, which makes Bombur very likeable.

At Hindustan Corporation, our commitment goes beyond products. Experience personalized assistance where we not only meet but anticipate your needs. From seamless installations to post-purchase support, our dedication ensures your satisfaction at every step.

شركة تنظيف فلل بالرياض

When it comes to in , a professional cleaning service is essential to maintain a pristine and hygienic environment. These services include thorough cleaning of every corner of the villa, from dusting high surfaces to scrubbing floors and sanitizing bathrooms. The skilled team uses advanced equipment and techniques to ensure a spotless result. services in not only save time and effort but also guarantee a clean and healthy living space for residents to enjoy. Trusting in expert cleaners can transform any villa into a sparkling oasis in the bustling city.

best gaming tablet under 200 Gaming tablets under $200…intriguing! Maybe there are some decent options out there after all.

schildkröten hurghada

In Hurghada, einer Stadt am Roten Meer in Ägypten, sind schildkröten hurghada der vielen Arten der maritimen Fauna, die Touristen und Meeresbiologen anziehen. Die Gewässer um Hurghada sind bekannt für ihre reiche Biodiversität und bieten ideale Bedingungen für verschiedene Schildkrötenarten, einschließlich der gefährdeten Grünen Meeresschildkröte und der Echten Karettschildkröte.

Could you explain the concept of the Clean Zone certification and how it has been implemented in South Korea and other countries?Visit us Telkom University