Building A Spirit of Inclusion: Pan Am and The Cultural Revolution

By Mirembe B. Birigwa

The legendary Pan American World Airways remains a bastion of nostalgia and cultural significance and serves as a case study in how airlines adapted their hiring practices to reflect the social movements of the 1960’s and 70’s. To maintain a competitive advantage, top companies thriving today are tasked with conveying a message of inclusion that matches the expectations of the traveler. The Civil Rights and Women’s Liberation movements motivated Pan Am to update their messaging to accommodate a broader audience and translate that shift to the marketplace. One of the solutions included reinterpreting strict Eurocentric beauty codes to suit a more diverse workforce. Pan Am also released advertising campaigns that highlighted African American flight attendants. My mother and her colleagues were a part of the drive to change Pan Am’s perception of exclusivity.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 President Lyndon Johnson signed the historic legislation to end racial bias in education, voting practices, places of public accommodation and employment. The Act ensured legal repercussions for hiring or terminating the employment of an individual on the basis of color, race, religion, or national origin. Title VII of the act created the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) to implement the law.

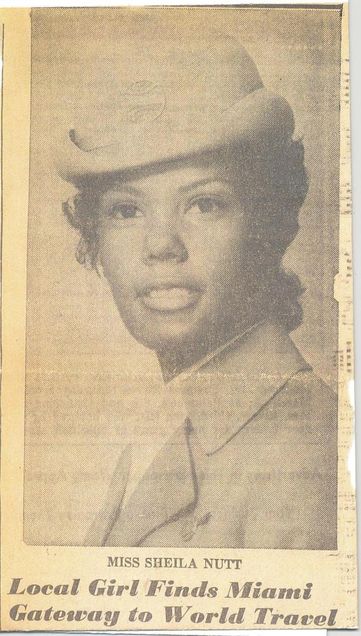

Pressure from the Civil Rights Act of 1964, including discrimination lawsuits against airlines, contributed to Pan Am increasing the number of diverse hires. From 1958 to 1969, 0.79 percent of Pan Am stewardesses were African American. My mother Dr. Sheila Nutt recalls being one of a few African American women sitting in the waiting room at the Pan Am interview held in Philadelphia in 1969. I also spoke with Oren Wythe, pictured in the Pan Am advertisement that ran in all major publications including Time Magazine and Newsweek. Oren grew up in Philadelphia as well. A talented violinist and excellent student, her French language fluency aligned with the iconic-style of the Pan Am brand. In the advertisement beneath a picture of her and a smiling team of Pan Am flight attendants reads, “Pan Am, The Spirit of ’75.” Flying during the seventies entered Oren into the unexpected role of cultural ambassador as the hospitality industry transitioned towards workplace inclusion.

While researching the integration of the airline industry, I sat down to speak with my mother, who now serves as the Director of Educational Outreach Programs in The Office for Diversity Inclusion and Community Partnership at Harvard Medical School. Following her fifteen-year tenure with Pan Am she wrote her Doctorate dissertation on Flight Attendant Stress and earned an Ed.D from Boston University in 1986. As a passionate advocate for diversity and inclusion, we spoke about implementing change in turbulent times and the effects of the historical movements on the aviation industry.

[Birigwa:]How did you find out about a career with Pan Am and were you concerned that you may not fit the standards of beauty?

[Nutt:]I entered beauty pageants while attending Girls High School located in Philadelphia in the 60’s. I first won local contests and was featured in Jet Magazine, a nationwide African American lifestyle publication. At that time the Civil Rights Act of 1964 created a policy that mandated diversity in all American institutions. I was first runner up for the title of Miss Philadelphia, a registered contest of the Miss America pageant. A fellow contestant who shared my disenchantment with the idea of becoming a teacher or a nurse as women were expected at that time—she told me the airlines were hiring. I felt a need to explore the world beyond my current reality so I applied to Pan Am with a friend, and together we were invited to interview at a local hotel. I was aware of the strict codes of appearance, however, at that time it was fashionable for women to groom themselves with great detail, never allowing a hair out of place and always keeping light, friendly make-up and of course a smile. The pageant world prepared me for the poise and demeanor necessary to stand out during the interview. I was used to being judged. I knew right away when I arrived that I was in the right place. All I had to do was get through the various levels of medical and language testing. The interviewer asked me a few questions in Spanish about where I liked to travel. I was able to answer correctly and he seemed to have a look of approval. Walking out of the interview I noticed I was one of the only African American women in attendance. I felt confidant that I made a good impression and that my life was about to change.

What challenges did you face as an African American Woman once you were hired?

Arriving in Miami and meeting my soon to be roommates posed a challenge in terms of finding accommodations. I felt the rental companies were not keen on renting to an African American woman and a colleague made a comment that we would have found a place if I was not with them. We were young women from various regions in the United States and it was 1970, so we had to navigate various racial attitudes and beliefs we held about each other.

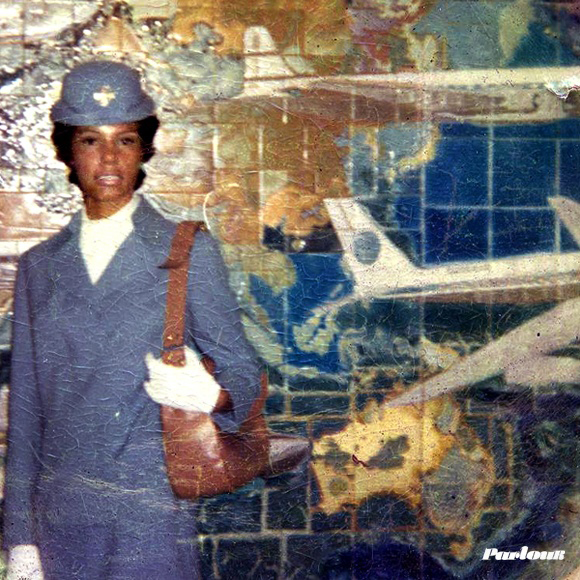

Flying also posed unique challenges when certain passengers unaccustomed to seeing African American women on the international flights often did not believe we were American. When passengers were unruly we found ways to express our discontent like withholding pillows or taking a longer time to respond to their call buttons. We also used our hair to express who we were. At that time an Afro was popular hairstyle for women to show solidarity to the Civil Rights and Women’s Liberation movements. Crossing the Atlantic with an Afro fluffed under a pillbox hat was an act of defiance that somehow made it through the appearance requirements before each flight. Some airlines banned the style. Traveling to Africa for the first time increased my self-confidence and affirmed my choice of self-expression through my appearance. I was able to make a statement about my personal politics that passengers interpreted as a subtle hint that I expected to be treated politely.

How were you affected by the change in corporate policies between 1969 when you first began flying and 1978 when the deregulation of the Airline Industry occurred?

When I first started flying I interpreted my role as beyond a caregiver. In the beginning we were poised to increase the comfort of our passengers flight experience in a way that mirrored the gender ideals of women as rulers of the realm of the domestic. Not only could we comfort an uneasy passenger, deliver a four course meal with dessert and beverage service–we could also execute an evacuation if necessary. We were prepared to change a diaper or two and kept diapers and bottles aboard the plane. It was not uncommon for a tired mother to hand us her infant to care for while she rested. Our role was to anticipate the needs of our travelers as well as rise to any technical challenge that may occur at 35,000 feet.

The Deregulation Act shifted the focus from training, discipline and customer service to strictly transporting persons in large numbers from point A to Point B. Where Pan Am once was the epitome of customer service, a stalwart of manners, diplomacy and luxury, the influx of many smaller airlines capable of moving large numbers of passengers for the least amount of money made it difficult to compete. We tried to for a little while, yet we were union organized and the smaller airlines were not, so they could afford to pay their flight attendants a lot less than we were paid. As well, there was an issue of the high cost of fuel at that time.

Deregulation completely changed the atmosphere of travel. The industry took a different path and the airline industry as a whole lost its luxurious feel. It was an end of an era when stewardesses shifted from glamorous icons to working-women balancing careers and families. Shortly before I started flying in 1970 it was customary to quit once you became pregnant or married. Pan Am had to change with the times. The general atmosphere was more relaxed.

When you were hired, did you believe you would remain a flight attendant for the rest of your working life?

When I was in training school the very first day I sat in the classroom, I knew that Pan Am was the ticket to my future. I was valedictorian of my training school class and I wasn’t sure what I would do with the rest of my life, I wasn’t sure what my position would be, but I knew that Pan Am was the vehicle for me to fulfill my destiny.

10 comments

Dear Mirembe Birigwa,

I read your interesting documentary about African-American stewardesses with Pan Am.

As we are inaugurating a Project focusing on the experiences/history of Pan Am employees, including interviews in written and video form may we ask you to contact us?

Thank you!

Best regards to you

Rich Gilbraith

As a fellow BU Terrier (COM & CLA ‘84) and a member of the Travelers Century Club, we’d like to invite Dr. Nutt to be our guest at an informal dinner meeting of the TCC, either in person or via Zoom, on Sunday 25 September at 5:30 p.m. We’d love to hear about her unique experience at Pan Am and her favorite ports of call. I hope she will agree to participate! We’d be honored to host her. Thank you!

Pan-Indianism is a philosophical and political approach promoting unity, and to some extent cultural homogenization, among different Indigenous groups in the Americas regardless of tribal distinctions and cultural differences. PeopleNet Fleet Manager

Thanks for sharing such great information, the post you published have some great information which is quite beneficial for me. I highly appreciated with your work abilities. Allied Universal eHub

I agree that many countries have faced cultural revolution. In some countries, it made positive impact while in other countries, negative impacts were seen because the natives denied accepting the cultural change. https://www.crazyzine.com/

Destiny Credit Card Login: You are looking for a method of logging into Destiny Card login. The following links to sign into your account on your Destiny card Our links are frequently updated.

Destiny Credit Card Login

It’s a platform where you can play the Cookie Run Kingdom in a browser by using Now.gg. Site open on your device. Now.gg Cookie Run Kingdom

I don’t know about you, but I always pay attention to the appearance of flight attendants, because they look very good, from hair styling to manicure. I don’t have time to go to a nail master, so I bought everything I needed, including products like rubber base gel kodi, to do my nails at home. But I think this brand is great for salons too because the quality is great.

If you need to see how much your $800k CD is worth, then try this:

How Much Does A $800,000 CD Make in A Year

If you need to see how much your $800k CD is worth, then try this:

How Much Does A $800,000 CD Make in A Year