Brand Heritage and Heritage Tourism

By Bradford Hudson

Brand heritage is an emerging topic within the marketing discipline, which suggests that the consumer appeal of products and services offered by older companies may be enhanced by the historical characters of their brands. The partially shared nomenclature with the well-established field of heritage tourism is more than coincidental, as both concern the interplay of history with contemporary visitor behavior. This conceptual article explores the common elements of brand heritage and heritage tourism, while also clarifying some important differences between the two fields.

Brand Heritage

The idea that brands may have a heritage dimension emerged at least a quarter century ago, when it was suggested in Harvard Business Review that the historical approach could provide brand images and themes for advertising. The term “brand heritage” was also mentioned in early work on brand equity by David Aaker, as an element of brand identity, but the topic was not explored in any depth. There has also been a recurrent but steady stream of literature on topics relating to older companies and their brands. This includes articles about the status and benefits of organizational longevity, and the benefits that may accrue from residual brand equity. It also includes topics such as authenticity and nostalgia. Scholars working in the area of corporate marketing and brand identity have recently suggested that historic brands constitute a distinct conceptual category. Mats Urde, Stephen Greyser, and John Balmer have argued that such brands require a different approach to brand management than younger brands. Activities related to brand heritage include uncovering aspects of heritage through archival and consumer research, activating that heritage through product design and marketing communications, and protecting that heritage through stewardship and attention to continuity.

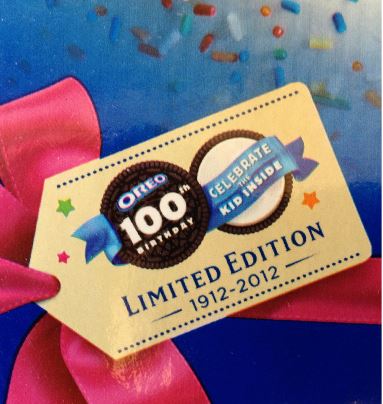

Examples of marketing related to heritage include the citation of company founding dates on packaging or in advertising, the celebration of corporate anniversaries, and the reprise of discontinued jingles or mascots. Such marketing may also involve references to a company in historical context or to iconic artifacts in possession of the company.

It could even include the creation of updated products that incorporate visual elements from prior versions, or the design of new offerings that refer to idealized or artificial memories of historical reality.

An excellent case of the brand heritage phenomenon is provided by the Cunard Line, which was founded in 1839 and eventually became the most famous operator of transatlantic ocean liners.

The brand was acquired in 1998 by Carnival Corporation, which reinvigorated the under-performing company by paradoxically focusing on both innovative product development and retrospective brand positioning. The result is new ships such as Queen Mary 2, which offer an integrated blend of modern amenities with historical references embodied in design, communications, and operations. Scholars working in the area of brand heritage hope to explain the nature and attraction of older brands, investigate the use of historical references in current marketing, explore the heritage aspects of brand equity, offer an additional dimension to discussions of product life cycle, and develop practical tools for executives who manage historic brands.

Differences in Focus and Scope

The fields of brand heritage and heritage tourism are closely aligned. Their theoretical foundations often overlap, some of the tourism literature predates similar work on brands, and brand researchers have cited tourism precedents regularly. However, before delving into these commonalities, it may be useful to examine the divergence between them. A clarification of the focus and scope of each topic will explain why these are separate sub-disciplines. The differences are several.

First, brand heritage focuses exclusively on marketing. It can be broadly defined to include consideration of the various financial, managerial, and operational issues that influence marketing decisions. This is especially important in services marketing, which concerns the interplay of production and marketing. Nonetheless, brand heritage is circumscribed by the marketing discipline and does not fully encompass the various functions of management.

In contrast, marketing is only one aspect of heritage tourism. The field also includes topics such as venue and visitor management, interpretation and education, historic preservation, and environmental sustainability.

Second, brand heritage considers the overall brand of a corporation and the subsidiary brands of its products or services. Related geographic locations, such as the sites of manufacturing or distribution facilities, are usually either unknown to the consumer or irrelevant to the buying decision. It could be argued that country of origin effects may influence consumer behavior in some instances, but this has not yet been demonstrated in the context of brand heritage. In any case, brand heritage is not exclusively or predominantly geographic.

In contrast, geography is often an important issue in heritage tourism. Perhaps the clearest examples of heritage tourism involve travel to particular locations such as historic cities, the birthplaces of famous individuals, or archaeological sites. Even when a broad cultural category is involved, it is often difficult to separate history from geography.

Third, brand heritage often involves the extension of brand identity onto new products that have no inherent historical characteristics or for which the historical element is understood to be trivial and falsified. In the case of the former, the brand heritage is separated from the immediate value proposition and the historic nature of the brand may function as an extrinsic cue for issues related to longevity, such as expertise or quality. In the case of the latter, the historic nature of the brand may be referential and intended to invoke an affective reaction, such as humor or nostalgia. The offering is understood to be a commercialization and interpretation of some related genuine artifact.

In contrast, heritage tourism often requires originality and an unbroken connection between offering and its corresponding historical reference. Even when reproductions are involved, they usually incorporate genuine artifacts (such as antique furnishings within a new building) or they are located on the exact site of any related historical event. The offering is understood to be as genuine and historically accurate as possible.

Fourth, brand heritage is oriented toward commercial endeavors in the private sector. The basic principles could be applied in other situations, but it is essentially a business subject. Cultural factors are relevant only in the context of consumer behavior, while political factors are peripheral issues that merely constrain marketing strategy. It could be argued that the increasing emphasis on corporate social responsibility requires an enlargement of this characterization. Nonetheless, the motivating factor in brand heritage is economic rather than social.

In contrast, heritage tourism is mostly a phenomenon of the public sector, broadly defined to include both government and non-profit organizations. The purposes of such offerings include cultural enrichment, education, and the creation or preservation of collective or national identity. There are exceptions, such as commercial attractions sponsored by firms to describe their historical origins, but these are often driven by peripheral social objectives and have vague connections to marketing strategy. Heritage tourism is seamlessly integrated with public policy in a way that brand heritage is not.

Lastly, brand heritage is usually oriented toward outbound distribution. Products or services emanate from a vague central location and are consumed remotely in retail units or at home. The exact distribution site is usually irrelevant and changeable.

In contrast, heritage tourism is usually oriented toward inbound distribution. The specific and unique geographic location is an important part of the value proposition for consumers. Given the relationship to public policy, it may not be possible to move the delivery location, even if logistically feasible. Distribution is inseparable from the local marketplace and the extended travel system, offering additional complexities in forecasting and ensuring demand. There are also usually limits to operational capacity and constraints on the ability to grow the brand.

The Hospitality Sector

An exception to some aspects of the divergence between brand heritage and heritage tourism is provided by the category of business for which consumer environments are an integral part of the value proposition. This includes the retail industry, especially companies with iconic flagship stores such as Harrods. It also includes the hospitality sector and its component industries including hotels and lodging, restaurants and foodservice, theme parks, and golf and leisure venues. For older firms in these industries, the dynamics of brand heritage and heritage tourism are often intermingled. The hotel industry offers an excellent case in point.

Unlike the manufacturing sector and many industries in the service sector, the hotel industry is geographically dependent. Even companies with multiple units and global brands that transcend specific regional associations have operations that are geographically specific. Many individual properties have their own distinct names, especially historic hotels that predate current management agreements. For iconic hotels such as the Parker House in Boston, now operated by Omni, these names are widely known and constitute subsidiary brands.

Many guests choose these hotels over competing alternatives because of their historic status, and some are even motivated to travel for the purpose of staying at famous hotels.

The hospitality sector not only tends toward geographic dependence, but also toward property dependence, meaning that it is constrained by a long term commitment to particular structures or land. For an iconic hotel whose identity is inseparable from its architecture, preserving the condition of the building and managing its relationship with the surrounding environment are important tasks.

The marketing ethic must extend from sales to stewardship, marketing responsibilities must include involvement in design and construction, positioning exercises must consider the social and cultural context, and marketing activities must be enlarged to include interaction with political leaders and community activists. Thus in the hotel industry, brand heritage encompasses a wide variety of duties in management and public policy, in manner similar to heritage tourism.

In manufacturing, the extension of brand heritage from genuine artifacts to reproductions may be relatively simple to accomplish. In the hotel industry, the task becomes more complicated. An older company with hundreds of hotels, encompassing both historic and modern properties, can probably extend its brand to a new development without losing any brand associations. However, an independent hotel may have problems when similarly extending its name to another property (or even a building extension) for the first time, as the positive brand effects from the original hotel may not transfer to the new location. Under such circumstances, maintaining an explicit connection with the original hotel will help alleviate doubts among consumers, but there may still be resistance and disappointment among those who are concerned about authenticity.

Thus in the hotel industry, brand extensions for historic hotels may be constrained by the same dynamics evident for heritage tourism venues.

Unlike the manufacturing sector and many industries of the service sector, the hotel industry has inbound distribution. Consumers travel from many different locations to the centralized production facility. Distribution is dependent on the extended travel system, supply is constrained by fixed capacity, and growth is often precluded by the surrounding neighborhood. Thus the hotel industry shares many of the characteristics evident in heritage tourism scenarios that relate to inbound distribution.

Similarities in Theory

Despite the differences in focus and scope highlighted above, there are many underlying similarities between brand heritage and heritage tourism. The most significant common elements are comprehensive frameworks borrowed from two other disciplines. The first is the framework of history. This includes the historical paradigm, meaning a way of thinking about the nature of human behavior and social institutions by examining their changes over time. The framework also includes the specifics of historical research methodology, the historical narrative as a form of expression deemed to have scholarly validity, and the vast content of our accepted historical inventory on trends and events ranging from military conflict to economic development. Even if history is creatively or selectively adapted to construct a particular interpretation, the basic historical approach is followed. Exploring, understanding, and interpreting the past are important in the marketing and management of heritage, whether for older companies or ancient cultural sites.

The second framework is that of marketing. Almost every aspect of basic marketing theory can be applied to either historic products or historic sites, ranging from strategy and market research to consumer behavior and communications. Any heritage site that attracts visitors, even those with managers who consciously eschew promotion, is subject to marketing phenomena.

Brand heritage and heritage tourism also share three important conceptual underpinnings. Although less comprehensive than the frameworks discussed above, they are nonetheless rich in theoretical content.

The first concept is that of identity. In the field of brand heritage, the exemplary article emerged from scholars working in the domain of corporate identity. Subsequent work has suggested that the history embedded in a brand is operative in defining the identity of the brand, but may also be involved in defining the identity of the consumer who acquires products of the brand, in a form of symbolic interactionism. Similarly in the field of heritage tourism, the definition and preservation of identity is a key theme.

The second shared concept is that of nostalgia. This involves a longing for the past, a sentimental recollection of yesteryear, or a penchant for objects or experiences that are associated with a prior era. The phenomenon of nostalgia has been studied in disciplines such as sociology and psychology, and has also been explored extensively in marketing literature related to older brands and products. Similarly in heritage tourism, nostalgia has been discussed extensively.

The third shared concept is that of authenticity. This considers the dichotomy between the true and false nature of objects or people, suggests that originality is preferred, and implies that reproductions are not legitimate. The topic of authenticity has been examined in a range of disciplines including American studies, anthropology, psychology, and sociology. It has also been explored in marketing and consumer literature, and represents an integral part of recent scholarship on brand heritage.

Similarly in heritage tourism, authenticity has been discussed extensively.

The Interplay of Brands and Venues

Academics working in the fields of brand heritage and heritage tourism, as well as practitioners working with older brands or tourism venues, should be aware of the similarities and differences between these two topic areas. In some cases, conceptual principles and marketing tactics may be transferable, and consideration of heritage practices in either realm may offer new perspectives. In other cases, a better understanding of these fields may discourage attempts to duplicate elements or methods that may be inappropriate.

For the hospitality sector in particular, there is much to be learned at the intersection between brand heritage and heritage tourism. Historic hotels may have multiple layers of brand heritage, involving both older corporate brands and the names of specific historic properties, which generate consumer demand. For many historic hotels, the buildings may also be integral parts of broader historical neighborhoods or landscapes, which generate tourism demand.

This multidimensional character is exemplified by the Château Frontenac. The famous hotel displays the Fairmont corporate brand, but enjoys even higher awareness for its specific property name. It is also located adjacent to the Citadelle, at the epicenter of the historic district of Québec City, which has been designated a World Heritage Site by the United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

In such instances, the conceptual overlap between brand heritage and heritage tourism constitutes more than a point of intellectual curiosity. The marketing of historic hotels can often benefit from the application of principles in both fields, and these related disciplines should be considered in an integrated fashion by both academic researchers and industry practitioners.

8 comments

i ask for the reference of above article.

i prepare research in hospitality heritage, thus, i need related reference

i ask for the reference of above article.

i prepare research in hospitality heritage, thus, i need related reference

Thank you. I read this interesting and useful page carefully and I learned a lot from it.Thankful

Best Dentist In Jaipur

A must read post! Good way of describing and pleasure piece of writing. Thanks!

Best love guru in India

This is clearly overwhelming, paying immaterial alert to it is key for tap on this viewpoint:

Dainik Astrology

I discovered your this post while hunting down some related data on website search. It’s a decent post. Keep posting and upgrade the data.

Speak To Astrologer

Write more high-quality articles. I support you. Thank you for the efforts you made in writing this article. Keep Blogging!!

best website development and designing company in Jaipur

Wow, very interesting, thanks for the information. If you need more info you can visit our website.

Free Astrology Guest Posting Site