The Rise of New Religions in Asia

The Rise of New Religions in Asia

March 19 – 20, 2018

Co-sponsored by BUCSA and the Fairbank Center, Harvard University,

with support from the Taiwan Ministry of Education and the Education Division,

Taipei Economic & Cultural Office, Boston

The Workshop will take place at:

121 Bay State Road

Boston, MA 02215

“The Rise of New Religions in Asia”

Organized by Robert Weller (BU Dept. of Anthropology)

Very much like the fundamental societal changes (industrialization, urbanization, increased literacy, shifts in values) in early and mid-nineteenth century Europe and the United States, radical changes also came with the post-WWII world order. These deep internal and external changes in the lives of peoples across Asia came with a vast range of new religions that offered orientation in this changed environment. These new religions drew on aspects of existing dominant religions (Islam, Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism, Sikhism) and reworked them or – more rarely – created new forms to mobilize disoriented segments of the population. They closely followed the activities of other new religions and adapted their techniques of proselytizing members. Many of these new religious movements in Asia are international in character and involve overseas communities as well as recruiting specific members from other ethnic groups. There has been fascinating scholarship on individual new religious movements specifically in South, Southeast, and East Asia, and some comparative studies have been done. However, movements such as Pentecostalism, Sufism, Wahhabism, or Dalit Buddhism that are directly connected with existing world religions have rarely been included, although it can be argued with reason that they are part of the same process.

The Conference bring together nine scholars working on new religions in Asia for a probing discussion on the underlying dynamics of their rise and development, as well as their role within the societies where they arose and the areas to which they have spread.

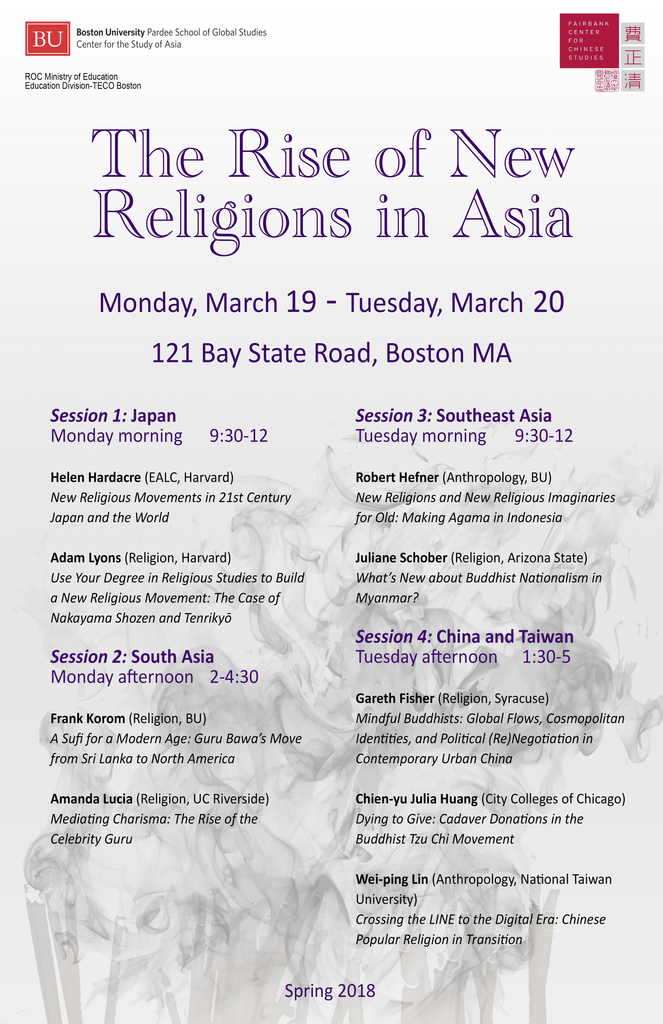

Schedule

Session 1: Japan (Monday morning, 9:30 – 12:00)

Helen Hardacre (EALC, Harvard): New Religious Movements in 21st Century Japan and the World

Abstract: Japan’s NRMs first began to appear in the late 18th century, growing in numbers and influence through the 19th century, coming under repressive state control in the first half of the 20th century. From 1945 to 1995, following Allied Occupation reforms and the promulgation of a constitution providing for religious freedom and separation of religion from state, they increased greatly in number, with some becoming mass movements, and one sponsoring a political party that now wields great political influence. The Aum Shinrikyō incident of 1995, when a religious group of that name released sarin gas on the Tokyo subway system, led to the creation of greater state oversight and renewed questioning of religious organizations’ tax status and political presence. After the 2011 earthquake, tidal wave, and nuclear meltdown, NRMs and other religious organizations’ reputations recovered through their massive contributions to disaster relief. The situation since then is characterized by the end of mass proselytization, but also by the reconfiguration of NRMs’ political alliances. In brief, the former coalition around progressive causes such as prevention of state influence in religious affairs has broken down, and a significant number now gravitate towards an omnibus ultraconservative lobbying organization called Nippon Kaigi (Japan Conference), which seeks a recovery of early 20th century society and culture.

Adam Lyons (Religion, Harvard): Use Your Degree in Religious Studies to Build a New Religious Movement: The Case of Nakayama Shozen Tenrikyō

Abstract: The academic discipline of religious studies was imported to Japan in the late 19th century, and since that time it has played an important role in the history of indigenous new religions. Scholars have served as advocates, critics, and even advisors for new religious organizations for more than a century. This paper takes the new religious movement Tenrikyō (f. 1838) as a case study and explores how Nakayama Shozen (1905-1967), heir to the ecclesiastical hierarchy, adapted disciplinary knowledge from his academic training in religious studies to guide the group’s organizational, theological, and political development. Based on archival research in Tenri and a reading of the writings of Nakayama Shōzen and other Tenrikyō theologians, I found that Nakayama’s mission in life was to centralize and rationalize Tenrikyō theology. He did so by comparing Tenrikyō to other religions so as to set “appropriate,” canonical versions of the scriptures, the sect’s history, and the founder’s

biography. I argue that Nakayama sought to move Tenrikyō away from mystical experience and charismatic preaching (characteristics of their early twentieth century activities) and towards a systematic theology grounded in textual exegesis. His biography suggests that his normative vision of religion was influenced by his training in religious studies. He sought to produce the kind of rational religion he regarded as fit for presentation in the classrooms of mid-century courses on religion. I conclude that Tenrikyō’s postwar development reveals the influence and authority of religious studies as a source for normative understandings of religion and as a mode of constructive theologizing in modern Japan.

Session 2: South Asia (Monday afternoon, 2:00 – 4:30)

Frank Korom (Religion, BU): A Sufi for a Modern Age: Guru Bawa's Move from Sri Lanka to North America

Abstract: The Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Fellowship is an American Sufi Community with origins in South Asia. It was formulated on the teachings of a charismatic oral preacher who was based in the Tamil-speaking region of northern Sri Lanka. Bawa’s enigmatic life prior to his arrival in the United States in 1971 raises interesting questions about agency and purpose: What led Bawa to leave his homeland? Why did he choose America? Were there historical and existential exigencies that pushed or pulled him in the directions he took? Based on multi-sited fieldwork, my paper will look at the period in Sri Lanka immediately before his departure from the island-nation and the period immediately after his arrival in the United States to assess this sage’s intentions, which requires sifting through a dense jungle of hagiography to contextualize what his intentions really were.

Amanda Lucia (Religion, UC Riverside): Mediating Charisma: The Rise of the Celebrity Guru

Abstract: In this talk, Dr. Lucia explores the rise of the celebrity guru as public figure and interlocutor for Hindu religiosity since Indian independence. Augmented by the increased impact of new medias and technologies, gurus have become so expansive in their influence that Jacob Copeman and Aya Ikeagame write of their “domaining effects,” wherein gurus move freely, transferring their power between multiple domains. Celebrity gurus have become influential politicians, businessmen, CEOs, and cultural and religious moderators. Dr. Lucia’s research investigates the impacts of the celebrity status of modern gurus, and questions the media and the public’s captivation with their charisma, their new religious movements, and their scandals.

Session 3: Southeast Asia (Tuesday morning, 9:30 – 12:00)

Robert Hefner (Anthropology, BU): New Religions and New Religious Imaginaries for Old: Making Agama in Indonesia

Abstract: Southeast Asia is a world area well-known for the its prolific generation of new religions and new religious movements. The world’s most populous Muslim-majority country, Indonesia is no exception to this Southeast Asian trend. From the first decades of the twentieth onward the country has witnessed the creation of a steady stream of new religions. Some draw heavily on indigenous pre-Islamic traditions of ancestral and guardian spirit veneration. Others engage in a creative bricolage of religious components mined more heavily from within Islam and Christian cosmologies. In the colonial and the early independence period (through the rise of the authoritarian New Order government in 1965-1966), many among Indonesia’s new religions were tolerated or even supported by state officials. Beginning with the New Order (1966-1998), however, state policy restricted these religions’ development. Since the return to democracy and constitutional freedoms in May 1998, state actors and – even more critically – religious vigilantes in society have intensified their efforts against new religions, insisting that modern Indonesian citizenship requires formal affiliation with one of Indonesia’s six state-recognized religions (agama).

In this paper I examine the social, political, and ethical forces both promoting and restricting the creation and flourishing of new religious movements in Indonesia. I explore the reasons for which state and society recognition of new religions has become far more difficult in democratic Indonesia. The obstacles preventing new religions’ authorization have greatly restricted the growth of new religions. However, I will show, the result has been, not the extinction of new religious currents and imaginaries, but the canalization of the creative forces of both into “religions” (agama) recognized by state and society. From within these established religious categories and communities, new religious currents show a remarkably transformative vitality.

Juliane Schober (Religion, Arizona State): What's New about Buddhist Nationalism in Myanmar?

Abstract: British colonial rule initiated profound changes to monastic institutions and to their relationship with the state in Myanmar. While colonial rule brought about a shift towards modernity, Buddhist sentiments and practices continue to influence and shape the changing political configurations of the state. This paper delineates the changing Buddhist engagement with politics, the monastic quest for renewed social relevance, and the state’s attempts to control religious formations. These histories reveal a genealogy of conflict and cooptation between these major institutions during a historical period in which institutions relies primarily on access to printing as the prevailing communication technology. In recent years, however, Buddhist public discourse is increasingly produced through digital communication media that amplify the aesthetic impact of the messages conveyed.

Session 4: China and Taiwan (Tuesday afternoon, 1:30 – 5:00)

Gareth Fisher (Religion, Syracuse):Mindful Buddhists: Global Flows, Cosmopolitan Identities, and Political (Re)Negotiation in Contemporary Urban China

Abstract: Based on fieldwork conducted in the first half of 2017, this presentation will examine complicated intersections of global and national influence that have produced a complex network of new Buddhist-based social groups among citizens of cities like Beijing and Shanghai. On the one hand, those interested in Buddhist religiosities face a political environment under China’s president Xi Jinping that is increasingly restrictive toward and suspicious of organized religion, and rank-and-file lay Buddhist practitioners are much more wary of the state than they have been at any time in this century. On the other hand, the ease with which Buddhist religious actors can form networks and associations with both foreign and domestic co-religionists through social media continues to increase, in spite of the state’s attempts to control it. Added to this picture is the influence of the complicated and sometimes contradictory dance between the Xi regime’s emphasis on promoting China’s national heritage and intensifying its participation in a global capitalist system that is heavily marked by western-based notions of individuality, competition, and compartmentalization of time. The presentation will example the complex effects of these factors on three trends in urban Chinese Buddhism: (1) the rising influence of Taiwanese-based Buddhist leaders; (2) the appeal of mindfulness-based meditation; and (3) the emergence of teahouse gatherings as a new Buddhist public sphere.

Chien-yu Julia Huang (City Colleges of Chicago): Dying to Give: Cadaver Donations in the Buddhist Tzu Chi Movement

Abstract: This paper will focus on a cadaver donation movement led by the Buddhist Tzu Chi Foundation – a phenomenon once made front page on the Wall Street Journal as “a surge of cadavers.” In contrast to the process of corpse donation in North America, the Buddhist Tzu Chi medical school in Taiwan formally forges ties between the donor’s family and the medical students who dissect his/her corpse and bestows the title of “silent mentors” on each cadaver used for the gross anatomy course and surgery simulation workshops. I posit the cadaver donation movement as a Buddhism-inspired effort for the personalization of dead bodies within modern medical science: the human body concerned in medical practice is not any body but some body. Drawing from my ethnography in Hualian, Taiwan, I will describe the medical humanity movement as two overlapping levels of “dying to give”: first, as a process of “giving” one’s dead body which can take various length of time ranging from a few months to six years; and, second, the personal and social conditions for, and the nature of the paramount commitment by both the donor and his or her surviving family. I then will discuss how the three discourses — the Chinese, the Buddhist, and the medical – compete and complement to address their authority on the dead body.

Wei-ping Lin (Anthropology, National Taiwan University): Crossing the LINE to the Digital Era: Chinese Popular Religion in Transition

Abstract: Most recent studies of new media and religion have focused on the effects of immediacy and outreach and less on the holistic religious transformations that they bring about. This article aims to fill this gap. In contrast to previous studies of web-based religion which analyze only the internet, I take a shrine in Taiwan as an example

to explore how the members adopted various media — from spirit medium and divination blocks to digital communication software — when they migrated to urban areas for work. I discuss in depth the instantaneity and individuality of one such communication service, LINE, which has allowed the spirit medium of the shrine to transcend the usual limits of place and time, providing immediate support and companionship to his followers scattered all over Taiwan. As a result, the “online deity” becomes more approachable, considerate and caring. A new kind of intimacy has thus emerged, by which people perceive and experience the power of deities in the digital age. This article also discusses the profound changes in religious practices and organizations correlating to the development of web-based religion. I point out that it has not become totally individualized: the family could play an irreplaceable role in digital religion.