BU Economist on College Rankings, Student Loans, and “Shacking Up” with Mom

Are stocks a good long-term bet? Financial planners say yes; BU economist Laurence Kotlikoff’s new book disagrees with that and other conventional wisdom. Photo by iStock/Dilok Klaisataporn

BU Economist on College Rankings, Student Loans, and Moving In with Mom

In his new book, Money Magic: An Economist’s Secrets to More Money, Less Risk, and a Better Life, Laurence Kotlikoff says everything financial planners tell you is wrong

“You can’t trust college rankings.”

“Paying, let alone borrowing, big bucks to attend an elite school is likely a huge waste of money.”

“Shacking up, even with Mom, is a very powerful way to safely raise your living standard.”

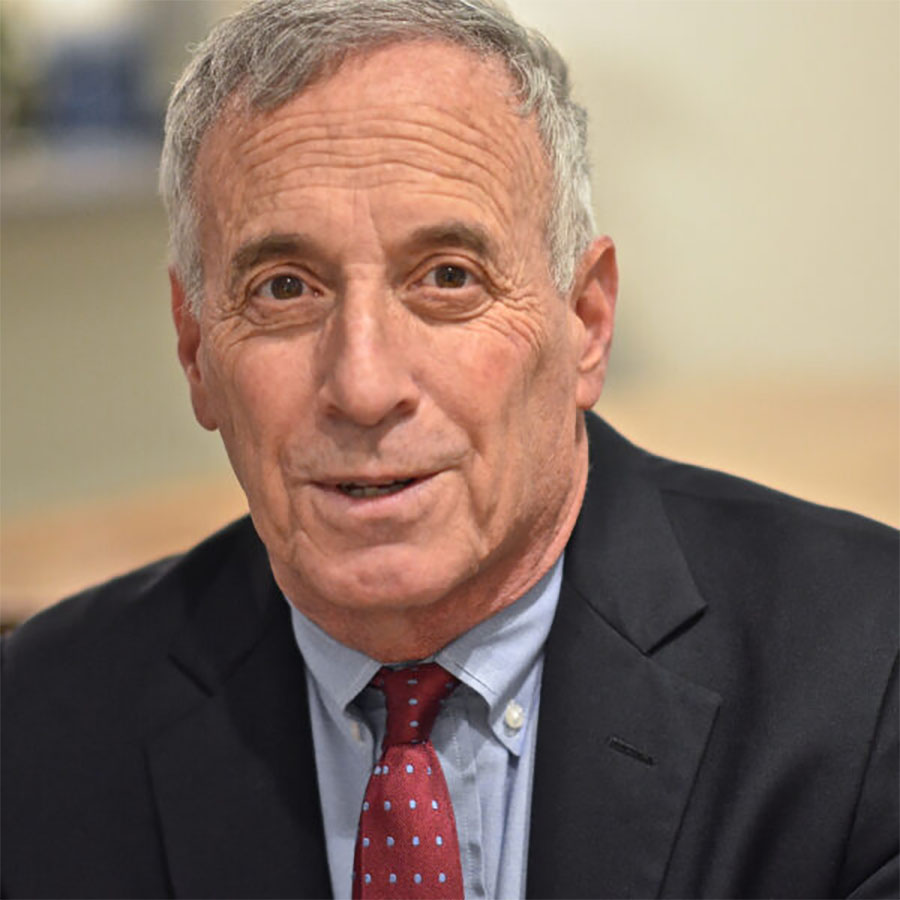

If these words from Laurence Kotlikoff have your attention, you may want to check out his new book, Money Magic: An Economist’s Secrets to More Money, Less Risk, and a Better Life (Little, Brown, 2022). Kotlikoff, a William Fairfield Warren Professor and a College of Arts & Sciences professor of economics, dispenses financial advice on college, home-buying, marriage and divorce, and retirement (don’t take early Social Security, which cuts your benefit and could cost you hundreds of thousands over your lifetime), as seen through an economist’s lens.

And through personal experience. His disdain for college rankings, he writes, followed the US News & World Report lack of interest in academics—notably BU’s economics department becoming one of the nation’s best in the 1980s and ’90s—while going gaga in its ratings over the University’s “splendid new gym, five-star dormitories, a gorgeous student center, and a state-of-the-art hockey rink.”

He also tells the true story of bringing a pseudonymous art history major to tears after eliciting that she was in hock $120,000 for college, yet couldn’t parlay her degree into a job offer. “This episode still haunts me,” he writes. “I apologized to Madeline profusely, in and after class. But the damage was done.” That illustrates his broader point about the risky investment of college: 40 percent of students drop out, and “borrowing money with a 40 percent chance of getting nothing in return is extreme high-stakes poker.” He suggests shopping for inexpensive schools, supplemented by cheap online courses from elite colleges, or attending more prestigious places on grants and scholarships, not loans.

Oh, and shacking up with Mom? That advice tweaks an old adage: two can live more cheaply than one.

Kotlikoff, named one of the world’s most influential economists by The Economist, has his own financial planning software company, whose services are free for BU employees. He discussed his book with BU Today.

Q&A

With Laurence Kotlikoff

BU Today: Why do you say conventional financial planning advice is “dangerous to your financial health”?

Laurence Kotlikoff: They calculate based on what you’re currently saving, which is surely wrong, [and whether] you’re spending some targeted amount they’ve given you, which is surely too high. The life-cycle theory of saving, developed by [economist] Irving Fisher, is the same behavior as squirrels, which is, you want to avoid starvation at all costs. If you’re going to possibly starve, you would never follow [conventional planners’] course of action; you would prefer to never be in the market. This has nothing whatsoever to do with common sense, with economics. It has everything to do with [financial] product sales.

BU Today: Conventional wisdom says stocks are a good bet long-term, but should be pruned from your portfolio as you near retirement. What’s your take on that advice?

Laurence Kotlikoff: Nobody with a PhD in economics or finance would agree to that. It’s like driving out the door. What’s the probability of totaling your car in five minutes? Very low. What’s the probability over 20 years that you’ll total your car? Significant. That’s the same thing here. If you have money in the stock market, what’s the probability of losing it all in an afternoon? Very low. What’s the probability of losing it all in 20 years? It’s not necessarily very high, but it’s high.

BU Today: If someone has made the mistake of borrowing for college and is awash in student debt, what should they do?

You have to pay it off. Otherwise, you’re in the equivalent of modern debtors’ prison. You don’t want to buy a fancy car; you want to buy a junker. You want to have your parents, if they’re investing in their retirement account, consider taking out money from their IRA, [use it to] pay off the student loan, and you pay them back at a lower rate than the student loan interest rate.

Oberlin College, where I sent my sons, is extremely expensive. I was able, out of my salary, to pay for my kids; as a consequence, I have much less money than I would otherwise have. They had a fine education, made lifetime friends, but I probably made a mistake not having them go to BU for free [via the faculty tuition remission], save the money, and give it to them when they graduated. If [students] aren’t saddled with [debt] directly, they’re saddled with it indirectly, insofar as the kids will inherit less money if the parents have spent down their wealth.

BU Today: Why is paying off debt, including your mortgage if you can, the best investment?

If I can borrow at, let’s say, one percent, and lend at 20 percent, I make the differential. This is the reverse: if I can reduce my lending and pay off a debt, where the lending’s at a low rate and the debt repayment’s at a higher rate, it’s the same arbitrage.

BU Today: So should we rent rather than own our homes, like the majority in some European countries do?

There’s a trade-off there. If we have 18 percent credit card loans, we should not be putting down money to pay for a house; we should be paying off the cards and then saving up for a down payment, and rent in the meantime. But we could also buy a place that’s less expensive. We could move to areas that have cheaper housing.

BU Today: Why do you suggest avoiding early retirement and waiting till age 70 to collect Social Security?

We can’t count on dying on time, at our life expectancy, even though Wall Street is telling us we can in order for us to keep our money with them so that they can keep charging fees. This is part of the scam they’ve been running. What economics says is that you have to plan to live the longest you could possibly live, because you might. You can’t set yourself up in a situation where you potentially starve or be in a terrible setting, like a Medicaid nursing home, if you can avoid it.

For low-income people, the odds of dying early have gone up. For high-income people, it’s gone the other way. You have to plan to live to your maximum age, but given the probability you won’t make it, what economics says to do is take a calculated gamble, whereby you plan to live to 100, but spend more before, let’s say, 70, and gradually less after. I’ll drop my spending every year by half a percent, because the chances are I’m not going to make it. That’s taking a gamble, but it’s never leaving me in a position where I’m starving.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.