Alum’s Book Recounts Long Overdue Search for Lost World War II Soldiers

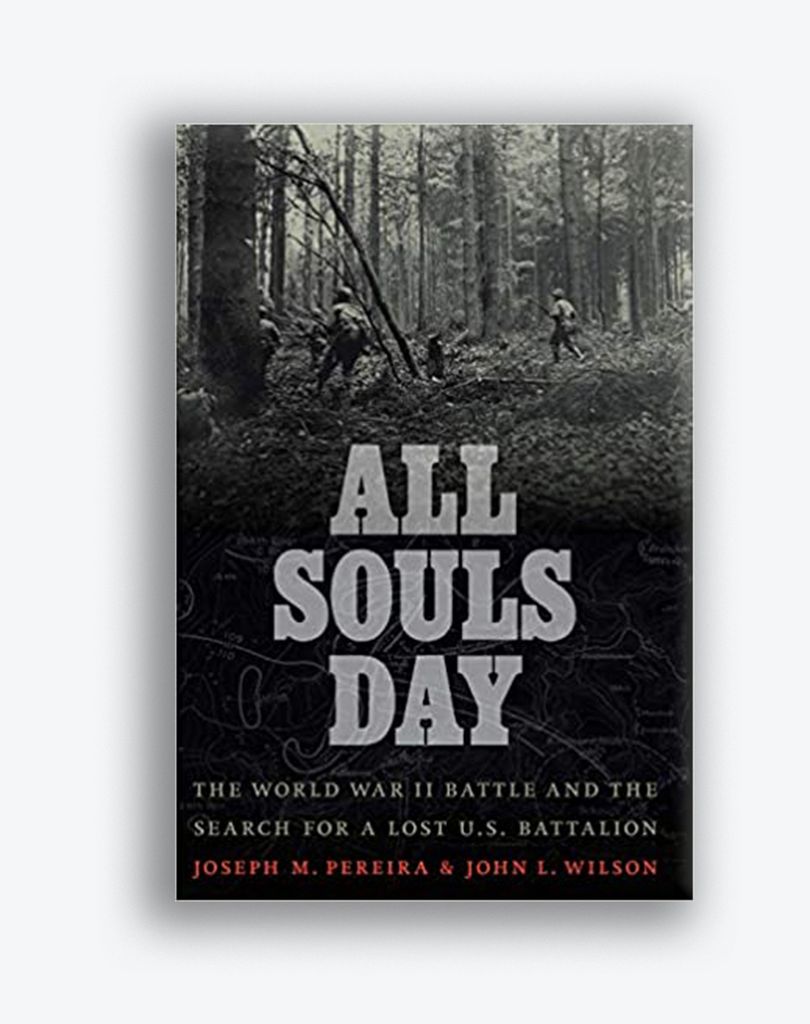

US infantrymen make their way through the Hürtgen Forest on November 8, 1944. Photo courtesy of Getty/Bettmann

Alum’s Book Recounts Long Overdue Search for Lost World War II Soldiers

Jack Wilson’s story of tracking down remains of his uncle and members of his uncle’s squad

For 66 years, Jack Wilson thought that his favorite uncle had been killed in the Battle of the Bulge, one of the biggest and bloodiest battles fought by US troops in World War II. Staff Sergeant John J. (Jack) Farrell died in 1944, but his remains, Wilson believed, were never found.

That conviction began to change one day in 2009, when perusing boston.com, Wilson was transfixed by a small black-and-white picture of a single boot left in Germany by US troops. For no apparent reason, he wondered if the boot had belonged to his uncle.

“I had this strange feeling that God was talking to me,” says Wilson (Questrom’76). “The only way I can explain it is to say that I’m the product of parochial schools.”

The rational part of Wilson’s mind told him that the boot could not possibly have been worn by Uncle Jack. The family had long ago surmised, based on information provided by the War Department, that Jack was missing in action during the Battle of the Bulge—a battle fought in Belgium, not in Germany. But another part of Wilson’s mind, the parochial school part, remained unconvinced. He set out to search for his missing uncle and others in his squad, a journey that would lead him to eight states, to Washington, D.C., and to Germany. It also led him, after deciding to write a book, to Joe Pereira, a former Wall Street Journal writer and an instructor at the New England Center for Investigative Reporting, which was founded at BU and joined GBH News in July 2019.

At a two-hour meeting over coffee, Pereira, the writer, and Wilson, a retired Bose Corporation executive, agreed that there was indeed a book in Wilson’s research, and the two got down to work. Last week, the 247-page product of their labors was published by Potomac Books. All Souls Day tells the story of Staff Sergeant Jack Farrell, his squad, and others in the 28th Infantry Division who died on or about November 2 (All Souls Day) 1944, not in the Battle of the Bulge, but in the Battle of the Hürtgen Forest. That six-month-long bloodbath, involving more than 100,000 US servicemen, began in September 1944 and ended in February 1945, yet is little known to most Americans.

The book also explains, in painful detail, why the Battle of the Hürtgen Forest is so little known: it is considered the greatest failure of leadership of US troops in Europe during World War II. Casualties exceeded 33 percent. “In comparison,” the authors write, “rates of loss at the Battle of the Bulge and at Normandy were 13 percent and 7 percent, respectively.” All Souls Day documents the failure of the US military to recover the remains of servicemen killed in battle, as well as the failure to notify families of missing servicemen whose remains had been recovered and identified. At least 150 men killed in the Battle of the Hürtgen Forest are still unaccounted for.

In Wilson’s case, it was not until September 2009 that his family learned from the army’s Past Conflicts and Repatriation Office that his uncle’s remains were catalogued in Hawaii, having been found by a German explosive ordnance disposal team during a search required before a house could be built. Wilson later learned that a German newspaper, Aachen Zeitung, had published his uncle’s name in October 2008 in a story about the remains of US servicemen that had recently been found.

In 2012, Wilson began to realize just how committed he was to learning more about the fate of his uncle’s squad when he found himself trying to persuade his wife to join him on a trip to Germany “to celebrate their anniversary.” Kindly, she agreed to go.

In a village near the battle site, he was told that it was common knowledge that the remains of many Americans were still buried in the area. “That had been something my research told me,” Wilson says, “but to hear it from a German citizen was incredible. I came back and decided to devote myself to this full time. I realized that if my family was in doubt about the death of a loved one, so must be the families of other soldiers in my uncle’s squad, and I decided to track them down.”

Wilson found the names of his uncle’s squad members in the National Archives, a place whose staff was far more accommodating, he says, than in the military offices he’d consulted. He cold-called their families to tell them what he had learned. Some did not welcome his sudden intrusion into their lives.

“A couple of people hung up on me,” he says. “I would wait and call back. It was very difficult for a lot of people. I could definitely hear some tears over the phone.”

He later drove or flew to meet with the families of the eight men who were in his uncle’s squad. “I felt it was something I had to do,” he says. “These people were as much in the dark as my family was. They had a right to know.”

For Pereira, Wilson’s book idea held a different appeal. Ever since he had written a high school essay on Stephen Crane’s Red Badge of Courage, where protagonist Henry Fleming is transformed from coward to hero in the course of battle, Pereira had been intrigued by the often circumstantial distinction between the fear and heroism.

“I was really fascinated with that,” he says. “I thought there were elements of it in Jack’s story. I wondered, if I were in that battle, would I be a coward, because [in the Battle of the Hürtgen Forest] there was in fact a stampede of cowards running from the Germans. For me, the appeal of Jack’s story was tremendous. It was Stephen Crane’s book in nonfiction.”

Pereira imbued his narrative with the hero/coward quandary by incorporating the story of Private Eddie Slovik, a 28th Infantry soldier, who, at roughly the same time that Farrell’s squad was facing down Panzer tanks, became the first person in 80 years to be shot to death by firing squad for desertion to avoid hazardous duty. He was killed, essentially, for being afraid to put his life on the line.

Pereira gives us a meticulously detailed and often terrifying recounting of the now ignominious Battle of Hürtgen Forest. His grim story is drawn from hundreds of documents, many of them firsthand accounts recorded in after-action reports and combat interviews. He also took advantage of a 10,000-word case study published in the journal Army History in 2010. Titled “General Cota and the Battle of the Hürtgen Forest: A Failure of Battle Command?” the study, which is now used in an academic course at the army’s Command and General Staff College, describes the many strategic errors and missteps that led to the defeat of American troops, including nine infantry, two armored, and one airborne divisions, in a forest that the commander of the 82nd Airborne Division called “an ice-coated Moloch with an insatiable capacity for humans.”

All Souls Day covers a lot of ground, moving from the early lives of young recruits in Farrell’s squad to a quick history of the 28th Infantry to the cold, bloody battle in a heavily forested corner of Germany, then taking on the failure, largely from ineptitude, of the military to find the remains of MIAs, as well as to notify families in those cases where they were found. And while we never learn exactly how Uncle Jack was killed, we do learn where and when he died, as well as where and when his remains were found and shipped to Hawaii.

Happily, the authors take us, 66 years after the Hürtgen Forest terror, to the cabin of a Delta Airlines flight departing Honolulu for Boston. “Before takeoff,” the authors write, “the pilot addressed the passengers on the intercom and explained that a special passenger was aboard the plane: a missing soldier from World War II was coming home to Boston after 66 years. He named the soldier and asked for a moment of prayer. All of the passengers stood and applauded.”

The passenger’s name was Staff Sergeant John Farrell. And his nephew, John Wilson, now knows that the boot he saw on boston.com really did belong to his Uncle Jack.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.