Leaders of US Cities Worried about Lack of Affordable Housing

IoC Menino Mayoral Survey finds cost drives people away

Affordable housing and climate change were two of the biggest concerns addressed in BU’s Initiative on Cities 2017 Menino Survey of Mayors. Photo by iStock/RSfotography

If you want to get mayors of US cities talking, says Boston University political scientist David Glick, ask them about affordable housing. Republicans and Democrats alike, mayors of big coastal cities and medium-size midwestern towns “are all worried about it,” says Glick, a researcher with BU’s Initiative on Cities (IoC). “Some are more worried about middle-class housing, some are worried about subsidized low-income housing.”

Glick, a BU College of Arts & Sciences (CAS) assistant professor of political science, is a co–principal investigator of the IoC’s annual Menino Survey of Mayors, and he says that widespread worry was one of the most striking findings of the current survey (its fourth). The survey explored mayors’ attitudes and concerns about a number of issues, among them sustainability, their relationship with state and federal governments, and how to thwart Trump administration actions that they oppose. Katherine Levine Einstein and Maxwell Palmer, both CAS assistant professors of political science, are the survey’s other principal investigators.

The IoC released the 2017 findings on January 23, 2018, at a public event at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C.

Of the 115 mayors of cities in 39 states across the country surveyed, only 13 percent said they thought their housing stock matched the needs of their constituents. Over half cited housing costs as one of the top three factors prompting residents to move away, outpacing other important concerns such as jobs, schools, and public safety.

Unsurprisingly, the survey noted that mayors of cities with the highest housing costs—those in the top one-third of the national housing price distribution—expressed the most concern about their housing stock. But even in the least expensive cities—those in the bottom one-third of the housing price distribution—“only 18 percent of mayors believed their housing served constituents ‘extremely well’ or ‘very well.’”

The lack of federal funds and insufficient bank financing were the obstacles to addressing affordable housing problems most frequently cited by mayors, according to the survey. For all the optimism mayors expressed about their ability to get things done, said Einstein, addressing the Washington audience, “the reality is that mayors are still limited by a lack of federal resources, particularly in important areas such as affordable housing.”

The mayors surveyed were all from cities with populations over 75,000. They represent cities “across every demographic, every region of the country, racial demographics, income, population,” Einstein said. They were interviewed in summer 2017 by IoC researchers, either by phone or in person. They were promised anonymity, she said, to encourage them to speak openly about sensitive issues, such as their relationship with state and federal governments.

“I think this is the gold standard of research on mayors and their leadership roles in cities because of the care researchers take to make sure they are really getting the voice of mayors captured in the responses,” said IoC director Graham Wilson, a CAS professor of political science, speaking at the press club. Wilson cofounded the IoC, a cross-University research initiative, in 2014 with Boston’s longtime mayor, the late Thomas M. Menino (Hon.’01), a CAS political science professor of the practice and IoC codirector.

Concern about climate change was another survey finding that Einstein highlighted: 84 percent of mayors said that human activities, rather than natural changes, have caused increases in Earth’s temperature. According to 2017 Gallup data, only 68 percent of the public believe that climate change is a result of pollution from human activities. In general, the survey noted, “Midwestern and northeastern mayors—in line with their general political liberalism—were more likely to attribute climate change to human activities relative to leaders of southern and western cities.”

About two-thirds of mayors agree, or strongly agree, that cities should aggressively address climate change even if it means making financial sacrifices. “This is again striking,” said Einstein. “Not only do they believe it’s a consequence of human activity, they also think we should take strong action to address climate change even if it means losing some revenue.”

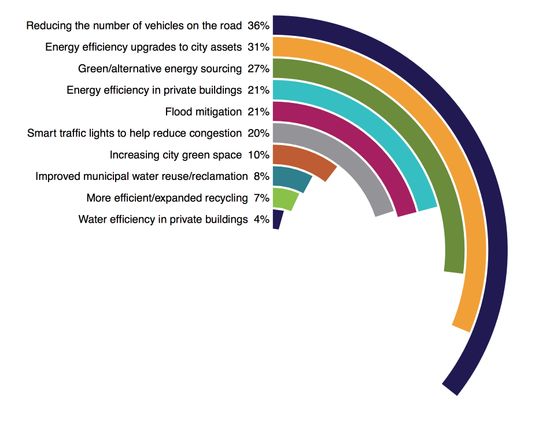

The mayors highlighted an array of steps cities could take to mitigate climate change; the top three were reducing the number of vehicles on the roads, energy-efficient upgrades, and green, or alternative, energy sources.

Democratic mayors were 50 percent more likely than Republican mayors to say that cities should address climate change even if it means sacrificing revenue, the survey found.

“This was by far the most polarized area of our survey,” Einstein said. Noting that IoC researchers asked the question about climate change in both 2014 and 2017, she added that while “Democrats’ views appear to be unchanged, Republicans’ appear to be trending more toward disagreeing and falling a bit more in line with national party trends.”

“Mayors have been leading on climate change for a number of years,” said IoC founding executive director Katharine Lusk, who was a policy advisor to Menino when he was Boston’s mayor. “What’s different this year is the tone and actions of the Trump administration, which have created newfound energy for local action and city-to-city cooperation. We wanted to know where mayors stand. It’s exciting that overall more mayors are willing to make financial sacrifices to mitigate the effects of climate change, but also troubling that the issue has become polarized even in local politics.”

On the question of their ability to counter Trump administration actions that they may disagree with, the mayors were divided, by party and by issue. They were optimistic, the survey noted, that they could do “a lot in response to objectionable federal-level actions pertaining to the environment or policing, but are less sanguine about their ability to counteract the administration when they disagree on education and immigration policies.”

The survey also showed that mayors were looking for new ways to be heard and to influence policymakers, including hiring lobbyists and working with their congressional delegations. They were more pessimistic than in years past about the financial support they were getting from federal and state governments, and this pessimism was shared by Republican and Democratic mayors. They told IoC researchers that they thought they had the resources to fund just half of their city’s infrastructure needs over the next five years.

And yet for all the obstacles mayors confront, Glick and other IoC researchers say, a significant number of those surveyed seemed to agree with Menino, who liked to say that being mayor was “the best job in politics.”

“Mayors really cheer you up,” Wilson told the Washington audience. “You can see them working with other people. These are people who will restore your faith in the capacity of democratic institutions to come to grips with problems in people’s lives.”

The 2017 IoC survey was supported with funding from Citi Community Development and the Rockefeller Foundation.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.