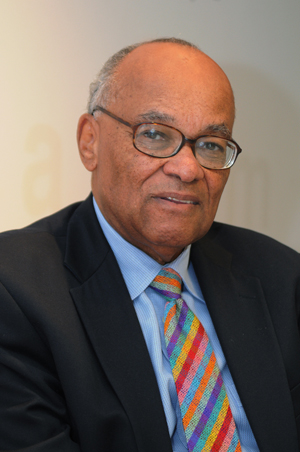

Hubie Jones’ Purpose-Driven Life

SSW dean emeritus recognized for lifetime activism

In 1953, Hubert Jones was a sophomore at the City College of New York, studying under the preeminent black psychologist Kenneth Clark. One day, Clark walked into class and told his students about an idea he was working on: writing a brief on his studies showing segregation’s psychological damage to black children, and filing it with a case that was being brought before the U.S. Supreme Court. The case was Brown v. Board of Education.

Clark’s brief would eventually help lay the foundation for the court’s landmark 1954 decision overturning segregation in public schools. But on that day, neither Clark nor his students knew if the justices would even allow it; the court had never before considered a social science brief as part of a case.

“Dr. Clark came back one day and said, ‘Okay. They’re going to do it,’” recalls Jones (SSW’57), dean emeritus of BU’s School of Social Work, who retired in 1993 and who has founded, led, or shaped more than 30 civic organizations in Boston both before and since his tenure at BU. “And then he said, ‘Here’s the brief. I want you all to read it and tell me what you think.’”

For the young Jones, it was a life-altering moment. “I mean, I really got it,” he says. “I saw a person who was an academic and a scholar who used his scholarship and his knowledge to advance social justice. And I began to think about social work as a profession that not only helped people or families, but that had a commitment to social change and social action.”

Now 77, Jones has spent the last half-century living out that commitment, translating scholarship into civic action as a leader, bridge-builder, and fearless advocate for urban children and racial equality in the city of Boston. He was recently awarded a $50,000 Purpose Prize, a national award given to social innovators over 60 who are making a significant social impact in their encore careers. The prize, often called the MacArthur genius grant for baby boomers, recognizes one of the organizations Jones has founded in recent years: the Boston Children’s Chorus, a multiracial, multiethnic chorus of students ages 7 to 18 from Boston and surrounding suburbs who perform across the country and around the world. Jones, one of 10 Purpose Prize winners, 5 receiving $100,000 and 5 receiving $50,000, was chosen from a pool of 1,500 nominees. He started the choir in 2003.

BU is also recognizing Jones’ lasting legacy as an activist scholar: this month, the School of Social Work announced the establishment of the Hubie Jones Lecture in Urban Health. The lecture series, which is partially endowed and set to begin in fall 2011, will draw national and global leaders in various areas of expertise to address urgent issues in urban health and social work. Since the 1990s, SSW has funded Hubie Jones Urban Social Work Scholarship awards for students, and its alumni association has honored graduates dedicated to the school’s urban mission with the Hubie Jones Urban Service Award.

“He was a true visionary here, and he continues to be a visionary in various roles today,” says Ken Schulman, SSW associate dean, who was hired by Jones in 1979. “His legacy was really to infuse the school with a sense of community activism and a tremendous energy around that. For Hubie, history was important, and preparing for the future was important. But we really had to be about what was happening in real life, in real time, as he would often say.”

In a city of old grudges, sharp elbows, and historic racial divides, Jones has made inclusion his trademark, creating or transforming cultural, educational, and community institutions that anchor Boston’s social landscape, from the Roxbury Multi-Service Center, where his leadership as director in the 1960s led to groundbreaking laws establishing special education and bilingual education in the state, to the pioneering service organization City Year, where he was a founding board member in the 1990s and has guided the agency from its Boston-based beginnings to one with global reach.

Jones founded the Boston Children’s Chorus (above) in 2003 with just 20 kids. Now with more than 350 students, the group has performed in Japan, Mexico, and Jordan, as well as in major U.S. cities, and its annual Martin Luther King, Jr., Day concert in Boston is televised nationally. According to the organization’s website, 100 percent of the chorus’ graduates have gone on to college.

“I always say that Hubie Jones is the conscience of Boston,” says Charlie Rose, senior vice president and dean of City Year. “He’s a person who is not afraid to take on any issue in this town. He’s not constrained by any of the political realities or any of the usual barriers. When he tackles something, it’s not about what’s comfortable or what’s expedient, but what is the right thing to do. And for my money, he’s always on the right side of history.”

Looking back, Jones says, he was lucky not to get swallowed by the urban dangers facing so many of the children he has fought for as a social worker. By age 19, when he found himself studying under Clark at CUNY, he says he had “danced and negotiated my way through what were the mean streets of the South Bronx,” a solid, working-class black community that had been hollowed out by drug trafficking.

His parents offered early examples of the power of education tied to service. Jones’ father, Hilma, was an organizer and legal advocate in the one of the best lines of work available to black men at the time—a Pullman porter, serving passengers on railroad sleeping cars. The elder Jones represented porters in discipline cases. Jones’ mother, Dorcas Robinson Jones, had come north by way of South Carolina; when she was 16, her family packed up in the dead of night after their next-door neighbor was lynched. She graduated from high school the same year as her two youngest daughters and went from working in the kitchen of a local child-care center to becoming its supervising teacher.

Just a few years after Jones completed his master’s in social work at BU, he found himself thrust in the thick of Boston’s civil rights movement. Inspired to action by leaders like Clark, A. Philip Randolph, and Martin Luther King, Jr. (GRS’55, Hon.’59), whom he had heard speak in Boston in 1956, Jones wasn’t interested in starting small. In 1963, while working for the Judge Baker Guidance Center, a social service agency for children, he began organizing a citywide work-stoppage protest called Stop Day.

As business leaders, politicians, and even the city’s more conservative black leaders pressured him to call off the protest, Jones stood his ground. “Even if we had wanted to stop it, we couldn’t have done it. That’s how powerful the idea had become,” Jones says. “In terms of getting into direct social action, that was my baptism by fire.”

The battle prepared him for a social crusade on an even bigger stage in 1968, when, as executive director of the Roxbury Multi-Service Center, he began noticing a systemic pattern of children in Boston being turned away from school, and took on the entrenched powers of the Boston public school system. “The school officials did what we knew they would do, which was to go into denial,” says Jones. “‘There’s no such thing as excluded children. We don’t push kids out of school.’ But we knew we had a problem that was endemic.”

A task force led by Jones exposed the illegal exclusion from school of 10,000 children, either because they were physically or mentally disabled, had behavioral problems, did not speak English, or were pregnant. The 1970 task force report, The Way We Go to School: The Exclusion of Children in Boston, rocked Beacon Hill politics and ushered in the state’s bilingual education law in 1971 and first special education law in 1972. The 1972 law, a first for any state in the nation, would become the model for the federal special education law passed three years later.

In 1977, BU came calling, asking Jones if he would consider the SSW deanship. “I said no,” he recalls. “People told me, ‘We don’t understand. Why don’t you want this?’ But the school needed to be totally reformed. It would be a lot of work.”

In time, Jones says, he began to consider how a post in academia could help further his mission. During his 16-year tenure at SSW, he would transform the school—turning over 80 percent of the faculty, increasing the school’s diversity, and reorienting its fundamental focus to one of urban social engagement. He also established a dual degree program in social work and public health that has become one of the leading such programs in the country. And under him, the school created one of the first part-time degree study programs, opening the field of social work to older, nontraditional students.

“I think I came to realize I could play a role in the education of a whole generation of social workers, and I would have a base from which to continue pushing for social change and social justice in this city,” Jones says. “And that came to be a very important thing.”

Read more about Jones’ 2010 Purpose Prize here.

Read about one of Jones’ new initiatives, the King Minute, launched earlier this month in conjunction with the Boston Celtics, here.

Hear the Boston Children’s Chorus here.

Francie Latour can be reached at comiskey@bu.edu.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.