Lab to Go

SED prof. brings advanced lab science to local high school students

Donald DeRosa may have long ago abandoned his plans to become a priest, but he approaches his calling — science education — like a man eager to spread the good word. DeRosa (SED’91,’01) is director of Boston University’s CityLab, MobileLab, and SummerLab programs, which give local high school students the opportunity to work in a state-of-the-art biotechnology lab. He’s also a clinical assistant professor at the School of Education, where he teaches a course on elementary science education and gives young teachers this advice: it’s all about attitude.

“If you walk into a classroom and see kids who are ready to undermine and sabotage your lesson plan, then you’re doomed to failure,” he says. “You need to walk in with the attitude: I have something great to share with you all, and you’ve got to hear this.”

That zeal has stuck with DeRosa over more than 20 years of teaching. After receiving a master’s degree in divinity from St. John’s Seminary, he became a long-term substitute teacher at Braintree High School in 1984.

"I just felt I wanted to try some other things," says DeRosa about his decision to leave the seminary. "I went into teaching, and I really liked it and decided to stay."

He went on to earn a master’s and a doctorate at SED and was teaching science when he was hired in 1992 to develop the curriculum at the newly established CityLab on the Medical Campus.

From the beginning, DeRosa’s approach to the courses has been to let the students learn by doing. “Anything in the lab that the students could do was better for them to do than to have the teacher do it,” he says. “Better to give students the opportunity to be successful, but also the freedom to feel like they could make mistakes and learn from them.”

He developed six lab-based courses, including The Case of the Crown Jewels, where students use DNA fingerprinting to solve a crime, and The Mystery of the Crooked Cell, where students perform electrophoresis of hemoglobin to identify sickle cell anemia.

“This kind of lab experience can be a little bit prohibitive for a lot of teachers,” DeRosa says. “There’s a lot of expensive equipment, and a lot of the teachers haven’t been exposed to either the science or the pedagogy of the molecular biology.”

Every Tuesday through Friday during the school year, about 50 local students and their teachers arrive at BU and spend a day completing one of these courses. DeRosa’s staff of three educators and CityLab’s assistant director, Meghan Moriarty (SED’05), guide the students through a prelab session, teaching them the basic concepts and establishing the scenario — the mystery that can be solved only with science — that they will follow throughout the lesson plan.

More than 70,000 students have come through the National Institutes of Health–funded CityLab since its founding in 1992 by Carl Franzblau, a School of Medicine associate dean, professor and chairman of the department of biochemistry, and director of the Division of Graduate Medical Sciences. Schools sign up in early May to schedule a visit the following academic year, and usually, says DeRosa, the entire year is booked within hours.

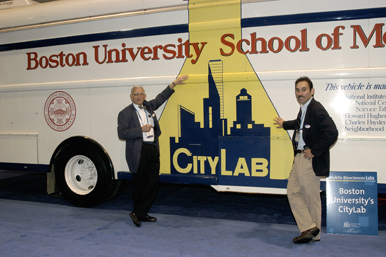

In fact, by the mid 1990s, CityLab was so popular, its creators decided to take it on the road. Franzblau came up with the idea when he visited a bloodmobile in 1995, and he and DeRosa spent more than two years putting a fully functioning biotechnology lab inside a bus. The MobileLab began visiting area schools in 1998.

“It’s difficult for schools to take a lot of field trips, especially with high-stakes testing,” says DeRosa. “So why not go out to them?”

In addition to the scientific equipment, the MobileLab is outfitted with a cordless microphone for the instructor and closed-circuit television monitors so the students working in the narrow space can view demonstrations of lab techniques. Every week during the academic year, the bus travels to a different school. For the first two years, DeRosa taught on the bus and drove it as well.

“Getting the bus driver’s license was harder than my doctoral exam,” he quips.

But he now leaves most of the driving and teaching to his staff. He spends more time writing grants, attending conferences, and helping other universities establish similar labs for their local students. So far, labs have opened in California, Texas, North Carolina, Maryland, and even Scotland. And the mobile versions are rolling through several other states, including Connecticut, Georgia, and South Dakota, with names like Bio-Bus and Science on the Move.

Bridgewater State College started its CityLab in 1996 with guidance and curriculum material from DeRosa and company. In 2000, Michael Carson, a Bridgewater associate professor of biology, helped secure an NIH grant that allowed his program to develop its own materials.

But even with this new independence, Carson says, DeRosa continues to work with the Bridgewater program, observing and giving feedback to its educators and helping to develop a summer curriculum for middle school students. DeRosa isn’t just enthusiastic about science, Carson says — he’s interested in discovering the nuances of how people learn.

“Don is very willing to go out on a limb and try something to see if it works better,” he says. “He has a willingness to say, ‘I can do this better; I can get these students to learn this material, and in the process, I’ll learn something about how they’re learning.’”

Indeed, in addition to classroom teaching and acting as CityLab ambassador, DeRosa has been a ski instructor at Blue Hills in Canton for more than 20 years, and he says that watching kids advance from doing snow plows to “stem christies” to parallel skiing has taught him a lot about assessing when students, of any subject, have mastered the basics. “It’s when they start to play a little bit with the skills they’ve learned,” he says. “That means they’re confident enough to move on. It’s the same thing in science education. We need to give students the opportunity to play with these ideas and concepts.”

Chris Berdik can be reached at cberdik@bu.edu.