Time to Activate

Sick children are cared for by parents, but what happens when they grow up?

Many children in the United States live with chronic disease; Type 1 Diabetes, sickle cell, arthritis, asthma, and cystic fibrosis are common diagnoses. Yet once children grow into adulthood and age out of the pediatric healthcare system, they often find themselves unprepared to advocate for their own medical needs. In the pediatric healthcare system, the child’s perspective is always important although ultimately the child’s guardian is legally responsible (e.g. signing informed consent for a procedure). Once the child reaches the age of 18 (age of majority in most states), the child retains full legal responsibility for choosing and consenting to treatments. With the sudden diminishment of the caregiver’s legal authority, the responsibility becomes the child’s to make the best decisions for his or her own body and lifestyle.

Without a gradual introduction to the realm of consent, a child cannot possibly be expected to understand the complexities of being a medical advocate. Effective transition is different from efficient transfer, where transition is the long-term accumulation of a child’s medical responsibility and transfer is simply the physical move to an adult care facility.1 Merely sending a child and his medical record to a new adult provider is not synonymous with actually preparing the child to care for his chronic illness into adulthood. Ultimately, the latter will be most advantageous to children, families, physicians, and the medical system at large.

Getting Started

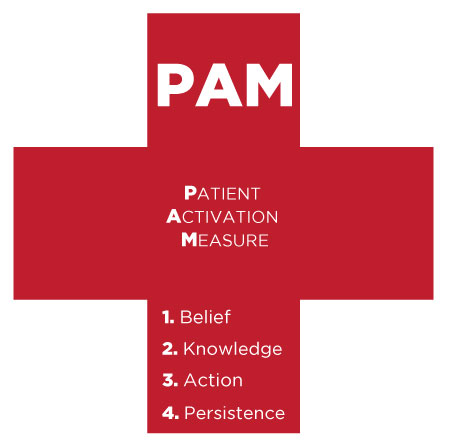

“Patient activation” as the mechanism for achieving meaningful and long-lasting involvement in pediatric chronic illness is a much-debated topic. Patient activation is defined by the patients’ completion of four stages: 1) understanding that their role is paramount 2) having the appropriate understanding and certainty to make a decision 3) having taken actual action towards health goals and 4) persisting in the event of adverse situations.2 It has long been known that actively engaged patients report improved health outcomes) and that successful chronic illness management skills can increase function, as well as minimize pain and healthcare costs. 3,4 The benefit to pediatric patients would be tremendous – particularly to their long-term physical, social, and emotional functioning. The problem remains: even with patient activation conceptualized, how can pediatric patients be ‘activated’?

Will Patient Activation be able to give sick children a more active say in their health once they are older? Photo Credit | Robert Lawton via Wikimedia Commons

The solution is a multifaceted approach, targeting the child, family, medical team, and medical culture at large. If medicine can be increasingly viewed as “consumer driven,” individuals may be less likely to accept doctors’ opinions without ensuring their own voice had been heard.2 For example, few people would tolerate going to a restaurant and being told what to order. Yet medical decisions are often chosen with the patient’s complete understanding.1

Medical education must be progressive and developmentally appropriate for patients and their families; too much too fast would only serve to be overwhelming. Nevertheless, patients and families must be empowered. This inevitably depends on the disease, age of child, culture considerations, and more. For example, a child living with arthritis needs an emphasis on physical activity as he matures. On the other hand, a child living with HIV should be educated about safe sex practices only when it is developmentally and culturally appropriate, involving the family along the way. Additional concerns, such as procuring health insurance with a pre-existing condition and medication prescription, are important to discuss with the child and family as transition begins to further success.

Achieving Independence

How can this success be measured? The Patient Activation Measure (PAM) was developed by Dr. Judith Hibbard, a professor of Health Policy at the University of Oregon, to assess patients’ degrees of involvement in their care. There are four subscales, which include ‘Believes Active Role is Important’ (e.g. “When all is said and done, I am responsible for managing my health condition”), ‘Confidence and Knowledge to Take Action’ (e.g. “I understand the nature and causes of my health condition(s)”), ‘Taking Action’ (e.g. “I am able to handle symptoms of my health condition on my own at home”), and ‘Stay the Course under Stress’ (e.g. “I am confident I can keep my health problems from interfering with the things I want to do”). 2 It is evident that these four core values of patient activation underscore the intersection of belief that the patient is an important actor in their medical care, thorough education of disease and lifestyle, and an active role. In a study with an adult population, the PAM was significantly related to health-related outcomes. Patients who score as being highly activated also experienced improved health-related outcomes when compared with their counterparts.5

The PAM is a useful tool for measuring patient activation, but the problem persists – how do we meaningfully activate pediatric patients? The answer in part lies in transitions clinics, an innovation that patients have been benefiting from for several years. Transition clinics occur within a given specialty (e.g. Rheumatology) with the goal of providing additional resources to prepare a child for adult care: primarily educational programs and skills training.6 The age at which a child becomes engaged in the transition clinic will varies in light of the age at diagnosis, social support, disease severity, and developmental stage. For instance, a child diagnosed with an illness at age fifteen should not begin the transition clinic right away, while another child diagnosed with the same illness at age eight may find the transition clinic appropriate at age fifteen.

The PAM is a useful tool for measuring patient activation, but the problem persists – how do we meaningfully activate pediatric patients? The answer in part lies in transitions clinics, an innovation that patients have been benefiting from for several years. Transition clinics occur within a given specialty (e.g. Rheumatology) with the goal of providing additional resources to prepare a child for adult care: primarily educational programs and skills training.6 The age at which a child becomes engaged in the transition clinic will varies in light of the age at diagnosis, social support, disease severity, and developmental stage. For instance, a child diagnosed with an illness at age fifteen should not begin the transition clinic right away, while another child diagnosed with the same illness at age eight may find the transition clinic appropriate at age fifteen.

Ultimately, the issue in part returns to the present medical culture: how doctors are trained to communicate with patients and the historically paternalistic medical model. It is plausible patients with doctors that have a strong and respect-filled relationship will have more positive medical experiences compared to those with poor patient/physician relationships. Thus, strengthening this relationship should be tandem to encouraging and initiating a transition process for pediatric patients.

References

1Peter et.al, 2009. Transition From Pediatric to Adult Care: Internists’ Perspectives. Pediatrics. 123(2):417-423.

2Hibbard et al., 2004. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): Conceptualizing and Measuring Activation in Patients and Consumers. Health Serv Res. 39(4 Pt 1): 1005–1026.

3 Von Korff et al., 1997. Collaborative Management of Chronic Illness. Annals of Internal Medicine.127(12):1097–102.

4 Glasglow et al., 2002. Self-management Aspects of the Improving Chronic Illness Care Breakthrough Series: Implementation with Diabetes and Heart Failure Teams. Annals of Behavioral Medicine.24(2):80–7.

5J. Greene and J. H. Hibbard. 2011. Why Does Patient Activation Matter? An Examination of the Relationships Between Patient Activation and Health-Related Outcomes. Journal of General Internal Medicine.

6 Crowley, et al. 2011. Improving the transition between paediatric and adult healthcare: a systematic review. ADC. 1:1-6.

Jennie David (CAS 2013) is a psychology major from Nova Scotia. She hopes to use her personal experience with Crohn’s Disease to support and inspire chronically ill children as a future pediatric psychologist. Jennie can be reached at jendavid@bu.edu.

Tagged as: medicine, patient care, psychology, pediatrics