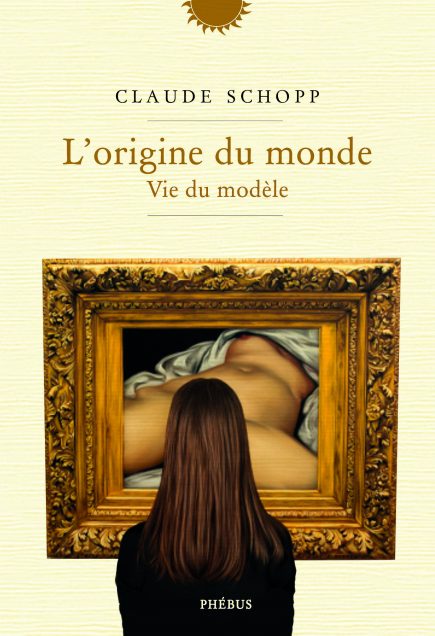

L’Origine du monde: Vie du modèle

Claude Schopp

L’Origine du monde: Vie du modèle

Paris: Editions Phébus, 2018. 152 pp.; 8 color ills.

$14.29

978-2752911780

L’Origine du monde was completed by the French painter Gustave Courbet in 1866. The painting presents a female nude lying against a bedspread. Her thighs open toward us, her jaundiced torso entangled in a white bedsheet. The edge of the canvas cuts into her thighs, truncating her limbs so that her torso occupies the entire canvas; her head, arms, and legs lie outside the frame. This cropping brings an unequivocal focus to the central element of the composition: the woman’s unshaven pubis mons and open labia. Despite the visual candidness of the painting, very little is certain about its history. L’Origine du monde was commissioned by its original owner, the Ottoman diplomat Khalil Bey, and went missing when the collector lost his fortune. The painting resurfaced in the mid-1950s and was purchased at auction by the famous psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan. From the painting’s beginnings to its current hanging in the Musée d’Orsay, one question has stupefied the predominantly male researchers drawn to the work: ‘Who is the woman in the painting?’[1]

This question about Courbet’s model is the focus of a recent book by the French literature historian Claude Schopp. Entitled L’Origine du monde: Vie du modèle, the book revolves around Schopp’s purported discovery of the woman’s identity, the Parisian dancer Constance Quéniaux. The book’s introduction explains how Schopp came upon this information; her name was buried deep within the stacks at the Bibliothèque nationale inside a letter written by Alexander Dumas. From there, Schopp defends his argument by presenting a careful account of his research, the letters that he reviewed and transcribed as well as his theories about the relationships between Courbet and Khalil Bey and between Khalil Bey and Quéniaux.

The second part of the book can be described as a micro-history. Schopp’s L’Origine du monde: Vie du modèle, functions as a precious document of the life of Quéniaux, a woman whom few would have found interesting if not for her status as the model in Courbet’s infamous painting. His biography of her takes pains to illustrate details about the documents that defined her life, from her birth certificate, to a photographic portrait by Nadar, to the condition of her estate after she passed away. Schopp extends his questions beyond merely ‘Who is she?’ but also to: ‘Where did she spend her childhood? What was her life as a dancer in the Paris opera like? How did she pass her days?’

A second look at the history of L’Origine du monde can help us to better contextualize Shopp’s project. L’Origine du monde is a painting that thrusts the female sexual organ before its viewers. The figure compels viewers to accept an unidealized image of the female sex. Since its first days, L’Origine du Monde, linked to the taboo of female sexuality, has caused anxiety for its male audience. The original owner, Khalil Bey, hid the painting beneath a green curtain and revealed it only for the pleasure (or consternation) of select guests. Lacan, too, hid the painting within a puzzle box, which (tellingly) only Lacan knew how to open. There is a certain poetic justice tied to the painting’s current display in plain view at the Musée d’Orsay. For the first time in its history, the painting requires no mediation. Without its veil, L’Origine du monde gives nothing to mollify the explicit presentation of the female body—no fig leaf or flirtatious gesture conceals her. The woman is at last present.

It is in this context that we receive Schopp’s book. His efforts to apply a name to the faceless figure in Courbet’s painting can be perceived as simply the most recent attempt to soothe the primeval anxieties invested in the work. Through L’Origine du monde: Vie du modèle, Schopp attempts to undo the mystery of Courbet’s painting with the stated objective of giving a name to the woman’s body. Yet, the identification of the model is just another kind of veil. Schopp’s book uses research, knowledge acquired about the model, to give an illusion of his own degree of access to the woman’s painted body. Just as Khalil Bey and Lacan established control over the figure by controlling the visibility of the painting, Schopp, too, positions himself as the gatekeeper before the work. Rather than humanizing the figure, the information Schopp provides in his book gives a false sense that identity can be encapsulated completely by representation. Furthermore, though Schopp describes Quéniaux’s career as a dancer at length, it is clear that his interest in her derives from Courbet’s painting of her genitalia rather than her achievements in the opera.

When it comes to approaching a painting as provocative as L’Origine du monde, the impulse to research the work may prove irresistible, but the form of interpretation matters. Claude Schopp’s L’Origine du monde: Vie du modèle sheds light on the biography of Constance Quèniaux, Courbet’s model and an otherwise unknown woman. However, Schopp’s meticulously researched book serves as just another attempt to establish authority over Quèniaux’s image. The underlying desire to acquire knowledge about Quèniaux, and therefore control, is the true subject of Schopp’s book. For the greater part of its history, Courbet’s L’Origine du monde was hidden in private collections. Now that the painting has found a home in the Musée d’Orsay, it is appropriate to ask: ‘Who is the correct viewer of the work?’ Perhaps it is time to embrace L’Origine du monde as a painting that exists only for itself.

Amber Harper

____________________

[1] See, for instance: Bernard Teyssèdre. Le roman de l’origine(Paris: Gallimard, 1996); Thierry Savatier, L’Origine du monde, histoire d’un tableau de Gustave Courbet, (Paris: Bartillat, 2006). Jr.