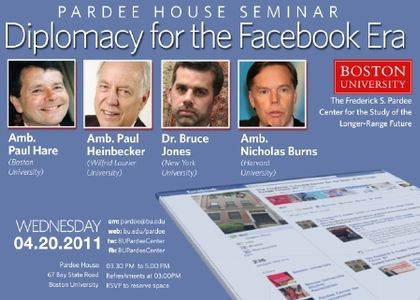

Pardee House Seminar Discusses “Diplomacy for the Facebook Era”

“Diplomacy for the Facebook Era” was the topic of discussion at a seminar sponsored by the Frederick S. Pardee Center for the Study of the Longer-Range Future on April 20. The seminar was organized and moderated on behalf of the Pardee Center by Amb. Paul Webster Hare, former British ambassador to Cuba who currently teaches in the Boston University International Relations Department.

“Diplomacy for the Facebook Era” was the topic of discussion at a seminar sponsored by the Frederick S. Pardee Center for the Study of the Longer-Range Future on April 20. The seminar was organized and moderated on behalf of the Pardee Center by Amb. Paul Webster Hare, former British ambassador to Cuba who currently teaches in the Boston University International Relations Department.

The featured speakers were Amb. Paul Heinbecker, Cathryn Cluver, and Dr. Bruce Jones. They are practitioners and scholars whose knowledge and interests focus on how diplomacy may –or may not – need to change to be effective in the 21st century. Each spoke briefly before a lively question-and-answer session with the audience.

Amb. Paul Heinbecker, a Canadian career diplomat who served in embassies in Turkey and Sweden as well as serving as the Canadian Ambassador and Permanent Representative to the United Nations, said while technology is changing the environment in which diplomacy happens, there will always be a need for traditional, face-to-face diplomatic meetings and negotiations.

He said he views WikiLeaks as the most important technological development, as it allows entire documents to be leaked and open to public scrutiny in a way that was simply not possible in the past. He believes WikiLeaks, ironically, will serve to increase secrecy in diplomatic operations as diplomats will become much more careful about what they say or put in writing for fear of it being leaked to a global audience.

Cathryn Cluver, Executive Director of The Future of Diplomacy program at the Harvard Kennedy School, said social networking technology is allowing government officials and diplomats to engage with citizens in a new and different way. While officials aren’t sending out traditional briefing statements via Twitter, they can “encourage engagement” with citizens who are interested in what government is doing.

In non-democratic countries, she cited “the dictator’s dilemma” in which an administration decides to turn television programs or internet access on and off, giving citizens a glimpse of what is happening around the world but tries to filter out negative perceptions of that country by outside sources. It doesn’t always work and may strengthen the drive by citizens to find ways around the ban on access to information.

Cluver, Heinbecker and Bruce Jones of New York University’s Center on International Cooperation and the Brookings Institution, all said that more needs to be done to ensure that officials in the U.S. State Department and national security agencies have backgrounds that include appropriate experience working in foreign countries as well as experience in working for or dealing with multi-lateral agencies, such as United Nations’ agencies, before they move up the ranks within the agencies.

“The business of dealing with China is fundamentally different than being on the ground in Kandahar,” and thus the people doing these different jobs should have appropriate knowledge and qualifications, Jones said.

Bruce Jones said while television “remains a profound source of imagery and information around the world,” he isn’t convinced that a government’s use of social networking tools to communicate with citizens will become a significant source of influence. He noted that in democratic countries, where people have more faith in governments, citizens might pay some attention, but in repressive countries where information has always been tightly controlled, it may be less effective or significant. “It depends on where you sit,” he said.

All three panelists were among the experts who participated in a meeting on diplomacy earlier in the day, also convened by Amb. Hare and hosted by the Pardee Center. Video of the seminar is available on the Pardee Center’s multimedia web page.