How Judaism Became an American Religion

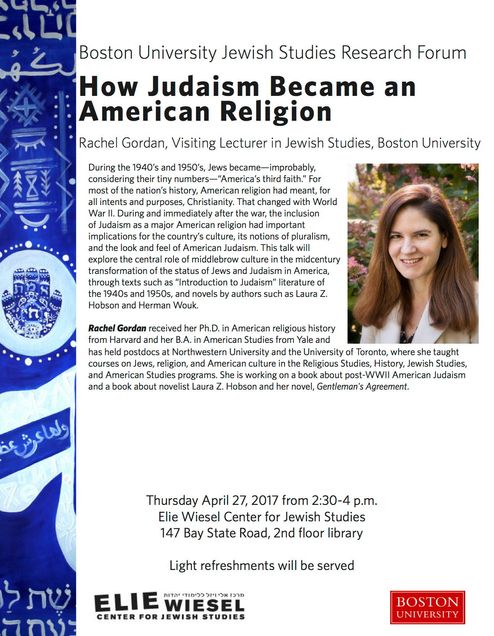

Our last BUJS Forum of the year took place on April 27 in the Elie Wiesel Center library. Our speaker, Dr. Rachel Gordan, joined us to speak about how Judaism rose to prominence as a major American religion in the 1950s and 1960s, even becoming known as “America’s third faith.” The forum was titled after her forthcoming publication, How Judaism Became an American Religion. In her lecture, she argued that “middlebrow culture” played a considerable role in the growth of the cultural understanding and prominence of Judaism during this post-war period.

Our last BUJS Forum of the year took place on April 27 in the Elie Wiesel Center library. Our speaker, Dr. Rachel Gordan, joined us to speak about how Judaism rose to prominence as a major American religion in the 1950s and 1960s, even becoming known as “America’s third faith.” The forum was titled after her forthcoming publication, How Judaism Became an American Religion. In her lecture, she argued that “middlebrow culture” played a considerable role in the growth of the cultural understanding and prominence of Judaism during this post-war period.

After the war, due to the devastation of the Holocaust and the fact that many American towns had a small population of Jews, there was a common misconception that Judaism was “no longer a living faith.” Middlebrow American literature worked against this misconception by simultaneously presenting Judaism as a living American religion and educating Americans about Jewish culture. “Middlebrow” writing, which was generally understood as “white, middle-class, and conservative in its values,” became a vehicle for this conversation.

Gordan noted that “the term ‘middlebrow’ did not appear until after 1920,” and came to mean “something blandly conventional.” However, in the earlier part of the 20th Century it developed as a distinct social strata of professionals, managers, and cultural workers. Most scholarship has examined the “highbrow” contributions of writers such as Philip Roth, Saul Bellow, and Bernard Malamud. Middlebrow authors such as Herman Wouk and Laura Z. Hobson have received comparatively little notice despite, Gordan explained, the ability of middlebrow culture to “announce Judaism to a mainstream public.”

Although Gordan mentioned a number of authors whose work could be considered middlebrow writing, she focused primarily on the work of Wouk and Hobson. In 1955, Wouk published a bestselling novel titled Marjorie Morningstar, which tells the story of a Jewish woman who was portrayed, remarkably, as an “American every-girl.” Natalie Wood and Gene Kelly starred in a movie adaptation three years after its publication. In the movie and the book, the American public witnessed Jewish holidays and events, such as a Passover Seder and a bar mitzvah, depicted as both American and middle class. Similarly, Hobson’s 1947 novel Gentleman’s Agreement clearly attempts to depict Jewish characters as “normal” Americans, combatting the common caricature of Jews in media as dishonest or scheming figures. Hobson’s vision, Gordan argued, suggested that “simply knowing someone was of Judeo-Christian origin was sufficient reason for respectful treatment.” Although such a standard is outdated by today’s understanding, it was an “imaginative leap toward integrating Jews into America’s national project” at the time of publication.