Layers of Love, Loathing, and Longing

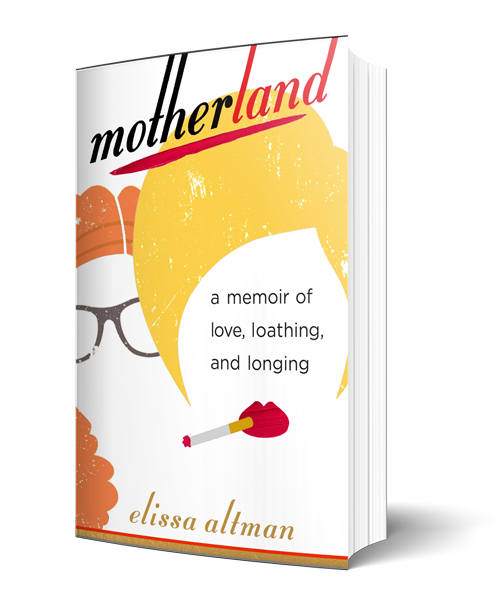

Elissa Altman thought she understood her mother, the woman she has known for 56 years—but that all changed when she started writing her latest book. In Motherland: A Memoir of Love, Loathing, and Longing, Altman (’83, CAS’85) delves into her complicated relationship with Rita, an 80-something former model and singer who doesn’t want to believe she is getting older. Alternating between memories of her childhood and present-day interactions with her mother, Altman reflects on their fraught history. Ultimately, writing the book allowed her to “come away with a different story than the one that I had been telling myself most of my life,” she says. For years, she saw her mother as a one-dimensional, beauty-obsessed woman who would never be pleased until her daughter emulated her ways. After writing Motherland (Ballantine Books, 2019) and learning more about Rita’s past, she saw her mother in a new light: complex, vulnerable, and broken.

Altman was inspired to write the book after penning a yearlong column she started in 2015 for the Washington Post called Feeding My Mother. The James Beard Award–winning food writer had intended to use the column to reflect on the issue of ensuring adequate nutrition in senior citizens by examining her relationship with food-phobic Rita, a “skinny glamourpuss” who—even though nearing 80—fears hearty eating will stop her from slipping into skinny jeans.

“But I discovered at the end of the year that I was not really writing about the practical issues surrounding feeding seniors,” says Altman. “I was writing our story. I was writing about issues of nurturing and sustenance and what they mean to me and what they mean to her.”

Writing the column, she says, felt like a natural segue into writing a book about their “very weird and clunky relationship.” Motherland was born.

Peeling the Onion

“She secretly sold her school lunch in order to stockpile makeup,” Altman writes of Rita in the book. “Reapplying it obsessively at the first sign of its fading, she produced a different face, a mask. At Performing Arts High School, where she was one excellent young singer in a sea of talent, she lived on black coffee and cigarettes to lose the weight she was prone to; it tumbled off her.”

When she started writing Motherland at the beginning of 2016, Altman’s early drafts focused primarily on her and her mother’s pasts, attempting to unpack formative tumults each experienced in their childhoods: Rita opens up about devastating verbal bullying she experienced that her daughter never knew about. Altman, on the other hand, vividly describes a time when her mother forced her to wear a dress and platform sandals when all she wanted to wear was the boys’ suit her father bought for her and snuck into her closet. But, then, Altman got a call that changed the trajectory of the book—her mother had suffered a crippling fall at home and would need her assistance around-the-clock.

Helping her mother through her recovery became the backbone of the book. Altman weaves memories of growing up in a residential part of Queens, N.Y., with present-day musings of living with her wife, Susan, in Connecticut and of caring for her injured mother.

“I had the audacity to leave New York City for good, to find love and happiness elsewhere,” Altman reflects at one point. “To make a home and family at which she was not at the center. To leave her for another woman. It had been a choice: my mother’s life or my own.” But Rita’s injury pulls Altman back into her orbit.

The past informs the present mother-daughter relationship. Early in the book, Altman recalls being a young child and comforting her mother after she flubs an impromptu performance at a cousin’s wedding. Rehashing her desperate attempts to calm Rita, she emphasizes the warped symbiosis of their relationship: “My mother is beauty and she is music, and I love her to my bones. If she is broken, we are both broken. If she is whole, we are whole.”

Writing is a revelatory process for Altman. In writing the Post column, for instance, she realized that she and her mother had at some point reversed roles. “I had become the nurturer and the sustainer,” encouraging Rita to eat healthily, “and she had become the child. And I think maybe it’s always been that way,” says Altman.

“The further I got into our story—it wasn’t a cathartic process—but every layer of the story revealed more and more about who I am and about who she is and who we are together,” she says. “As a food writer, I often speak in terms of, ‘peeling the onion.’ You peel it, peel it, peel it, you get to the core. You never know what you’re going to excavate. You never know what you’re going to find. And one has to be open to that because it’s not always what one wants to see.”

Altman is drawn to memoir: Motherland is her third after Poor Man’s Feast (Chronicle Books, 2013), which chronicled her finding love with Susan and her changing relationship with food, and Treyf (Berkley, 2016), about the religious, cultural, and familial contradictions she faced growing up.

“I don’t have a fictive impulse either as a writer or a reader,” she says. “I find the human condition to be revealed, for me personally, so much more readily in memoir. It allows me to step into the lives of other people with whom I might have no connection or relation to.”

Hope and Understanding

Since publishing Motherland, Altman has received emails and messages from readers who have found a personal connection to the book, and who want to discuss their own complex relationships with their mothers.

“I want people to read the book and understand the possibility of hope that comes with understanding the human condition,” she says.

For her, that hope came from learning more about her mother’s childhood and helped her approach her relationship with her mother more sympathetically. She was able to get a fuller picture of the woman she thought she knew so well.

“As humans, we tend to view people as cardboard cutouts because it’s the way we can most easily metabolize who they are,” she says. “It’s more complicated to get to the place where you understand someone else’s motivation and what has created them, and see them as a full human with all of their faults, upsides, and downsides.”

Altman says her mother—her toughest critic—has read the book. And when it came time for her to give her feedback, “I held my breath, of course. My mother suffers from narcissistic personality disorder. So I always sort of joke and say my mother believes that all publicity is good publicity. But in fact, she does. And she gave me the biggest compliment that she could—she thought 95 percent of the book was accurate, which is astonishing to me because narcissists write their own truths. So for her to say that was an enormous gift to me, both personally and professionally. It meant that I did my job.”