Who is the Citizen Artist

To a weaver in India, the citizen artist is the painter whose commission keeps him employed. To a homeless child in Houston, it’s the harpist who performs a classical piece at her day school. To a gay teen, it’s the actor who takes up his battle to show him he’s not alone.

By Lara Ehrlich | Photo by Cydney Scott

The term citizen artist means something different to each person touched by an artist’s work. Though their creative work takes myriad forms, citizen artists share a dedication to their craft, an entrepreneurial spirit, and a commitment to society. “If you focus only on your art, you will become isolated from the world,” says College of Fine Arts Dean Benjamín Juárez. “If you focus only on the marketplace, you will lose your soul. If you focus on an idealistic life, you will not be able to make it sustainable.” CFA encourages its students to embrace the complexities of the artistic dream when deciding how to live and work as artists in today’s world. Here’s how three alums are rising to the challenge.

James Fluhr

A black chair on a dim stage. Pounding club music wars with the stillness. There is a sense of anticipation, “like hearing electricity without seeing anything turn on.” Enter James Fluhr (’11), skinny as a taut wire. His dark, earnest eyes plead with the audience even before he speaks.

“Mid-January when everything else outside seemed to fade to gray, and there was no pulse to be found in anything, it would snow. The snow would fall, delicately covering everything. It made everything that seemed broken beautiful again.” In Our Lady, a solo performance based on his life, Fluhr invites the audience into a world of fantasy and nightmare to battle with him against the “Monster of Hate.” In the play’s climactic moment, a broken boy transforms into a goddess drag queen armored in rhinestones and glitter. She is “Our Lady,” who saved Fluhr’s life, onstage and off.

The citizen artist is “a warrior. I’ve decided that this is the war I’m going to fight, and I battle it with my art. I battle ignorance. I battle hate. I battle fear.”

During his senior year at CFA, Fluhr had a confession to make. He visited his father in Tennessee, prepared for the worst, and revealed that he was gay. His father surprised him. “It’s okay,” he said. “I love you no matter what.”

Fluhr was “so softened by how open and loving he was” that he returned to school relieved. The Sunday before Christmas, his father surprised him again. Fluhr was standing outside in the snow after work when his father called, “spitting rage through the phone.” He had seen Facebook photos of his son in drag.

“He told me I was disgusting. He said, ‘Be a man. Be a real man; stand up and be a man.’ He was talking to me almost as if I was five, and he kept calling me buddy, a word he used when I was in trouble as a child. He said he wasn’t there to buy my dresses.”

Fluhr’s father had cosigned the loan for his final semester of college, and “he said I would never be able to pay back his loan and that no one was ever going to hire me. I was a worthless investment. He threatened to pull the funding unless I could give him a good reason not to.”

Fluhr pulled the loan himself. He has described his father’s hatred as a monster that turns its victims against themselves; for the first time, he understood why so many gay youth had turned to suicide. “My father had ripped me apart completely. Either I was going to fall further into darkness, or I was going to cover myself with rhinestones and glitter and pull myself toward the light.”

Photo by Kalman Zabarsky

Fluhr worked odd jobs to pay his rent and finish school. In the meantime, he used his father’s words as the foundation for Our Lady, an artistic and political response to the suicide of gay youth. The play’s title character was inspired by the photos Fluhr’s father had seen on Facebook, in which he was dressed as Marc My Jacobs, a drag persona he had developed to emcee the annual ball hosted by BU’s LGBT social organization, Spectrum. “The image of me in drag that so repulsed my father was an image that was powerful to me,” Fluhr wrote in an article for Huffington Post. “I thought I could force that woman to become greater and more magical. Her makeup would become war paint. Her costumes would be transformed into armor. I could use the weapon that condemned me as a tool to fight for a way to love myself.”

Fluhr workshopped Our Lady for his senior thesis and staged a full production during the 2011–12 season of the Boston Center for American Performance (BCAP). The following year, he performed Our Lady at the 2012 New York International Fringe Festival (FringeNYC), the largest multi-arts festival in North America. Not only did the play open in New York, it received four stars from Time Out New York, and was hailed “as stunning a piece of performance art as you’re ever likely to encounter” by Backstage.

More important to Fluhr, his work resonated with audiences. In the play’s climactic moment, he dons a white dress reminiscent of his Spectrum ball costume and enters the audience as Our Lady.

Photo by Kalman Zabarsky

“I’ve touched people’s hands and had them break down in front of me,” he says. “I feel like they’re battling with me, and so when we finally win, it’s an emotionally charged moment.” As one audience member writes on the Our Lady Tumblr site:

The show brought many of my life experiences to life on the stage in NYC, even though they exist far away in the state of Texas. The monster stayed with me for a large part of the show, but with your final performance in full Our Lady armor, I felt okay. I felt secured. I felt SAFE.

“I saved myself by creating this story,” Fluhr says. “And when I started to share it, I saw how it could help and change others. As an artist, I feel like a warrior. I’ve decided that this is the war I’m going to fight, and I battle it with my art. I battle ignorance. I battle hate. I battle fear. The fear affects both sides—the person who’s attacking and the person who is attacked. If we can conquer the fear, we can find peace. That’s where my battle leads.”

Meghan Caulkett

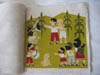

“We’re going to create a story together,” Meghan Caulkett (’10) says to the three- and four-year-olds gathered before her harp. “I’m going to play a modern piece called ‘Song in the Night,’ by Carlos Salzedo, and you tell me what you think it sounds like.”

The notes start out slow, each pluck of the strings pure and distinct. Then a leisurely glissando glides into double harmonics as she presses her palm against the strings, pinching two at once for a soft thrum. There will be no “Bah Bah Black Sheep” for these kids. They lean forward, entranced by Caulkett’s fingers as she plays the kind of music that many people never hear outside of an orchestra hall. For the children of Houston’s House of Tiny Treasures, an early childhood development center that serves homeless families, this concert is awe-inspiring.

Photo by Anni Hochhalter

The House of Tiny Treasures is just one of the venues at which Caulkett performs through her outreach program, 47 Strings. For each of the 47 harp strings, Caulkett will play a concert for a homeless shelter, elementary school, or nursing home. “I don’t perform background music or filler classical music,” she says. “I’m trying to give the audiences really high-quality classical solo and chamber pieces. Just because people haven’t been exposed to classical music isn’t a reason to play easier pieces. You just have to present the music in a way that’s accessible.”

Her fingers pause on the strings.

“So what do you think that bit sounded like? Is it daytime or nighttime?” she asks the Tiny Treasures.

“Daytime!” they shout. “The parents dropped the kids off at school, and it’s daytime in the city, and the kids play outside, and puppies come to play with them.”

By the end of the piece, the children have created a story that “reflected a very typical day for them. The tapping on the soundboard sounded to them like a knock on the door, and the quiet part reminded them of falling asleep. So, when I played the whole piece again, they understood it.”

The kids try the instrument after the performance. None of them has seen a harp before today, and they are hesitant, plucking tenderly at the strings. Ignorance of the harp is not unique to this audience; Caulkett has found that her instrument mystifies almost everyone. “Every time I go to a gig, people tell me that they’ve never seen a real harp. Even some of my fellow musicians in orchestra concerts are still baffled by it—and they sit 10 feet away from me!”

Caulkett admits that even she was unfamiliar with the harp at first. She grew up in a nonmusical family in the small ski town of Tahoe City, California, and discovered the piano on her own at the age of five. When a friend introduced her to the harp in high school, she fell in love the instant her fingers touched the strings. Her school didn’t have an orchestra, so she arranged her own parts and played with the school wind ensemble. Since the musical opportunities in Tahoe City were limited, she committed to weekly private lessons in Reno, Nevada, an hour away.

A citizen artist is “involved in the community. It’s our responsibility as professional artists to help shape culture and help the general public understand what we do and why it’s relevant.”

As a student in CFA, Caulkett found the musical community she had been seeking. She performed with the orchestra, the opera, and—a highlight of her academic career—for Prince Charles’s sixtieth birthday while studying abroad in London. Now a graduate student at Rice University, Caulkett aspires to be the principal harpist for a major orchestra, though her ambition is tempered by the fact that each orchestra employs only one full-time harpist. She doesn’t allow the lack of traditional opportunities to discourage her, however, and is already forging a robust career. “In music, I think you have to create your own opportunities,” she says. “Sometimes, if you want to perform, you have to initiate something yourself.”

Caulkett has found that her work with 47 Strings has made her a better artist. Sharing her passion for music nourishes her enthusiasm for her work at Rice, as well as her role as the principal harpist with the Baton Rouge Symphony. “I definitely want to do orchestral playing as my career,” she says. “I love being part of a group and working with other really talented musicians, but I think it’s equally important to be involved in the community. Musicians can often get into the mindset of practicing by ourselves for eight hours a day. I feel that it’s our responsibility as professional artists to help shape culture and help the general public understand what we do and why it’s relevant.”

Aaron Sinift

At seven, Aaron Sinift (’02) told his mother, “Someday, I’m going to change my name to Harry Whitecloud and travel to India.” When he finally made the trip at the age of 24, he felt as though “I was returning to an essential facet of my heart.” He loved India’s color, vibrancy, and culture, so different from his native Iowa. He was distressed by the country’s extreme poverty and drawn to the work of the ashrams, service institutions promoted by Mahatma Gandhi to help India’s rural poor maintain self-sufficiency by spinning and weaving khadi cloth. “The khadi is so beautiful and so fragrant, and rough in certain ways,” Sinift says. “Gandhi wore it, and it has a lot of soul.”

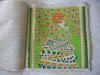

Sinift bought a traditional jhola [jho-la] shoulder bag made from khadi cloth and printed with an image of Gandhi. “I was attracted by the tender awkwardness of the artworks created by anonymous ashram artists for common people. These are authentic Pop Art creations from the very roots of the land.” As a CFA graduate student, he hung the jhola on the wall of his studio and found that his bold, colorful paintings began to take on some of the jhola’s themes. His advisor, Professor of Art John Walker, noticed the change. “That bag is not an artifact,” Walker said. “It’s a living work of art.” This casual line stuck with Sinift, and it would direct the course of his career.

After graduating from CFA, Sinift took a job as the preparator at a New York gallery, Feature Inc., and painted in his Brooklyn studio with the hope of being discovered. “I was seeking the approval of people who didn’t know I existed, and I decided to reinvent myself into the person I wanted to become. I wanted to be an artist who serves those in need and to create a community in which people feel connected to one another.”

Sinift invited the ashrams to create a book made entirely from khadi cloth featuring screen- and block-printed artworks by 24 artists from 8 countries. He commissioned well-known artists like Francesco Clemente, Yoko Ono, and Chris Martin, as well as emerging artists such as Tamara Gonzales, Tim Wehrle, and Pushpa Kumari to contribute one page each. He called this project the “Five-Year Plan” and aimed to print 180 copies, which would be packaged in handmade jhola bags.

In accordance with Gandhi’s philosophy, the Five-Year Plan would need to be entirely nonprofit and autonomous, so instead of seeking institutional backing to assist with the printing cost, Sinift raised more than half of the funds by preselling the book online. “Citizen artists need to find ways to fund their work with modest means,” he says. “When we do so, we realize that we’re not helpless. We realize how much power we have.” Sinift pledged the first $25,000 revenue to Doctors Without Borders and the remaining proceeds to the next Five-Year Plan project. But first, he needed the cloth.

“Citizen artists need to find ways to fund their work with modest means. When we do so, we realize that we’re not helpless. We realize how much power we have.”

Sinift traveled to the outskirts of New Delhi to to find an ashram that would collaborate on the Five-Year Plan. During a visit to an ashram in Meerut, Sinift met with the director, “a stony guy who was used to people coming to buy their cloth because it’s cheap. When I showed him the drawing that I made for the cover of the book, his eyes began to water. He saw that I respected his labor and was not there to take advantage of it. That was the moment I knew I was on the right track.”

Sinift commissioned 1.4 kilometers, almost a mile, of khadi from the Manav Seva Sannidhi Ashram in Modinagar, which employs 700 spinners, the majority of whom are women over the age of 55. The ashram also employs 45 weavers (mostly men over the age of 45), and 35 helpers. Most of these workers are Dalit Muslim or low-caste Hindu, and are the sole providers for their families. Spinning and weaving the khadi for the Five-Year Plan created more than 2,400 days of work for the ashram and kept 100 families employed for a month.

The artists, too, benefited from the Five-Year Plan. “Most of the artists are very poor,” Sinift says. Each artist received a copy signed by all of the contributors, and “they can sell their copies of the book and use the proceeds however they wish.” Indian painter Pushpa Kumari, whose intricate work is inspired by stories from the Hindu epics, is using the proceeds from the sale of her book to help build her house. True to Gandhi’s ideals, Sinift has not profited from the Five-Year Plan; to support his life and his art, he works part time at the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C., and the Katzen Arts Center at American University, which he finds as fulfilling as his work with the ashrams.

And Sinift is just getting started. He plans eventually to take the project a step further by beginning a book from seeds, commissioning organic farmers in India to grow one ton of cotton that will be spun into the thread used to weave the khadi. He will invite the farmers, spinners, and weavers to contribute original artworks, completing a “sustainable cycle of collaboration.”

“The ashram workers provide incredible value to the world by supporting Gandhian ethics and helping people to maintain self-sufficiency,” Sinift says. “The people in Doctors without Borders dedicate their lives to saving people in crisis. The Five-Year Plan gives artists a chance to make a tangible contribution to the common good, simply by doing what they already do naturally. If people just give what they do naturally, everyone can live together with dignity.”