|

|

||

|

|||

CAS

prof gives keynote address to international conference

Barth urges fellow anthropologists to recognize the power of individuals

By David J. Craig

As a young anthropologist living among indigenous New Guineans in 1968, Fredrik Barth posed questions that many social scientists might have asked: how are boys in the isolated tribe initiated as men? and, what cultural traditions get passed on from generation to generation?

|

|

|

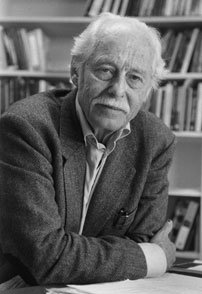

| Fredrik Barth Photo by Vernon Doucette |

|

Simple queries, but Barth’s observations helped chart a new path

for anthropology. The meaning of male fertility varied substantially among

the tribe’s 180 people, Barth found, because elders improvised complex

male initiation rituals to make them colorful and compelling. His findings

challenged prevailing structuralist social theories, which saw cultural

knowledge as being transferred relatively smoothly between generations.

“I showed that people don’t simply act out their culture,

but make decisions that have important historical consequences,”

says Barth, a CAS professor of anthropology. “It would not have

been enough to simply draw a correlation between what appeared to be the

regular features of the tribe’s initiation rituals and its ideas

about fertility. By considering how people navigate and maneuver within

social structures, you can see how cultural history shifts and changes.”

Barth drove home that same message to some 4,000 colleagues last month

at the annual meeting of the American Anthropological Association in New

Orleans. Delivering the international conference’s prestigious keynote

address, Barth called on anthropologists to focus their research “on

the processes that happen between people, not abstract structures that

we extract from them.”

Among the people

While anthropology has moved away from “the gross structuralist

analyses” that dominated the field 40 years ago, Barth says, even

today too few anthropologists give proper attention to variations in social

processes because it is difficult to do without getting bogged down in

details. “It’s easier, and still considered proper,”

he says, “to do structuralist analyses.”

Barth certainly has the credentials to advise colleagues on how to approach

research: few anthropologists have conducted as much fieldwork or worked

in as many places. A native of Norway who built the anthropology department

at Norway’s University of Bergen from scratch in the 1960s, Barth

has written ethnographies based on his firsthand research in Iraq, Sudan,

Afghanistan, Iran, New Guinea, Oman, Bali, Bhutan, China, Norway, Britain,

and the United States. He is best known for his work on ethnicity: his

seminal 1969 book Ethnic Groups and Boundaries describes how dynamic group

identities tend to be.

And while many anthropologists give up field research to concentrate on

theoretical work upon receiving a senior academic post, Barth has barely

slowed down. “I’d rather be out on an adventure than building

up my authority in one area so that I can have my own turf to defend,”

says Barth, a warm, unassuming man who turns 75 this month. “I guess

I just have this curiosity about the world.”

So today he spends several months of the year in the isolated Himalayas

of Bhutan, which he says is “the last place in the world where the

traditional Buddhist monastic system is still fully in place and functional.”

His next book will focus on how Buddhist traditions are disseminated among

the society’s classes, including “very sophisticated monks,

illiterate people, and everybody in between.”

Barth lives in extremely primitive conditions during his two-to-three-month

stays in Bhutan, sleeping on wooden floors in small, unheated shacks,

and eating little more than dried meat and tea flavored with rancid butter.

He likes to work alone and brings no other researchers, except occasionally

his wife, the anthropologist Unni Wikan.

“The Bhutanese people, like many isolated people, are remarkably

hospitable,” Barth says when asked to describe the satisfactions

of his work. “I can arrive unannounced and unknown and just move

in with them. And then there is the kind of gambler’s thrill you

get in the field from knowing that at any point you can make a mistake

and end up collecting inadequate information. Sometimes it’s a matter

of making the right guesses to get what you need, and that’s exciting

to live with.”

Anthropological lessons

Barth’s prominence in anthropology results also from his theoretical

contributions, which were mostly developed early in his career. While

living with nomads in what today is southern Iran during the late 1950s,

for instance, he developed a complex theory of “generative processes”

to explain how populations of nomads fluctuate in accordance with the

availability of green pastures and other economic factors. The theory

was useful to social scientists who subsequently studied the demographics

of nomads in the Middle East.

In addition, Barth prides himself on being a spokesman for his field,

which he believes should contribute to public policy discussions. At BU,

where he has taught every fall since 1997, Barth encourages students to

extract lessons from their research that apply to current political issues

and to speak out. (When not in Boston, Barth splits his time between Bhutan

and Oslo, where his wife teaches.)

“I think anthropologists are in a unique position among social scientists

because our subjects aren’t numbers in a demographic chart or survey

respondents,” says Barth, who frequently gives public lectures and

writes op-ed pieces. “Rather, we live with them and learn their

problems, attitudes, and priorities.

“Anthropology has a tremendous amount to share because most people

know their own worlds and not other people’s worlds,” he continues.

“The challenge for anthropologists is to do fieldwork and come home

and not only write about it for other anthropologists. We need to identify

important policy debates going on and join them.”

![]()

13 December 2002

Boston University

Office of University Relations