Three ENG professors honored by election to top professional group

By David J. Craig

Evan Evans has spent his entire career studying the physics that underlie the molecular machinery inside living cells. In the emerging and often misunderstood field of biomedical engineering, such basic research is not exactly headline-grabbing stuff.

Yet Evans, an unpretentious man who would rather discuss

the intricacies of cell membranes than professional laurels, recently

received a resounding affirmation of the value of his work: he was one

of three ENG professors of biomedical engineering inducted into the College

of Fellows of the American Institute for Medical and Biological Engineering

(AIMBE) -- an honor reserved for the elite 2 percent of scientists in

the field.

|

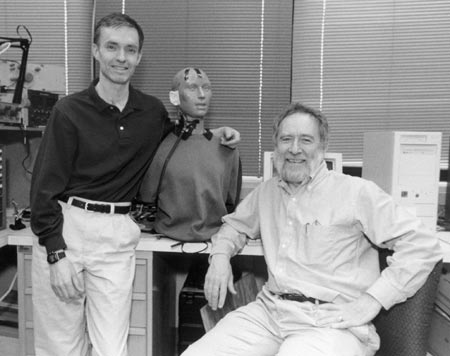

| ENG Professors of Biomedical Engineering

James Collins and Steven Colburn (from left) were elected recently

to the College of Fellows of the American Institute for Medical and

Biological Engineering. They were judged by their peers to be among

the top 2 percent of scientists working in the field.

Photo by Vernon Doucette

|

ENG Professors James Collins and Steven Colburn also were admitted to the 400-member college at the annual induction ceremony at the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, D.C., on March 3.

"This means that these professors represent the very best and brightest of all biomedical engineers in the country and that each has made a major impact in his area of expertise," says Kenneth Lutchen, chairman of ENG's department of biomedical engineering. "Very few biomedical engineering departments can boast such a large number of faculty members admitted to this body."

The new inductees join Lutchen, Carlo De Luca, an ENG professor of biomedical engineering, research professor of neurology at the BU School of Medicine, and director of BU's NeuroMuscular Research Center (NMRC), Herbert Voigt, an ENG associate professor of biomedical engineering, Gerald Gottlieb, a research professor at NMRC, and Serge H. Roy, a research associate professor at NMRC, as AIMBE fellows.

Speaking up for science

An

umbrella organization with which almost all biomedical engineering organizations

in the United States are affiliated, the AIMBE was established in 1992.

Its primary functions are to promote the field of biomedical engineering

and to lobby Congress for research dollars. In 1998, its members convinced

the National Institutes of Health to recognize biomedical engineering

as a distinct discipline, making it easier for those working in the field

to attract government funds.

Evans, whom Lutchen describes as "a giant" in the

study of nano-microscale biomechanics, says that AIMBE meetings provide

an opportunity to interact with other prominent biomedical engineers,

who tend to come from a variety of academic backgrounds and work in myriad

subspecialties.

|

| Evan Evans, ENG professor of biomedical

engineering, is considered a leader in the study of the biomechanics

of living cells. Photo by Fred Sway

|

"I see my job as trying to understand how nature works, and what makes it fail, which ultimately informs developments in health care," says Evans. "The whole point of this organization is to bring together those working in the basic sciences with those doing more applied work. AIMBE's national meeting has enough breadth and sophistication to attract the interest of everybody in the field."

Colburn is director of BU's Center for Hearing Research and is best known for his work on how the human brain processes auditory signals from both ears simultaneously. His research has led to the manufacture of hearing aids and to virtual-environment laboratories to test hearing. Because biomedical engineering is a young field, he says, informing the public about what biomedical engineers do is important.

"A lot of my work is easy to justify because it has applications for health care that are pretty obvious," says Colburn, who studied electrical engineering as an undergraduate at MIT in the 1960s, when MIT had no biomedical engineering department. "But funding for this field, especially for those who do, specifically, engineering-oriented research, is still being developed.

"So the main responsibility of being a fellow is that you act as sort of a spokesman for the field," he continues. "Whatever recognition you have as a scientist, you lend to the field. That is an honor, and it's also very important because the public still is confused by the field, mainly because of how broad it is."

Collins is one inductee who promises to lend plenty of visibility to the field in the next year. The codirector of BU's Center for BioDynamics, he is best known for developing genetic applets -- genetic mechanisms that can be implanted in a patient and programmed to control cell function. He hopes soon to launch a company that will develop a commercial application of the "genetic toggle switch" that he and graduate student Timothy Gardner (ENG'00) created last year. The man-made gene acts as an on-off switch that controls when genes manufacture certain proteins and DNA, and has implications for treating a variety of diseases.

"We also recently found that tactile sensitivity in people with elevated sensory thresholds can be enhanced by introducing mechanical noise -- that is, random vibrations," says Collins. "Thus, diabetic patients or elderly people who have trouble feeling their feet might be aided by a vibrating insole in their shoes."

Collins is now working with Sensory Technologies, a Providence start-up that licensed the noise-based technology last year, in hopes of developing a commercially viable device.

He agrees that biomedical engineers have a long way to go in promoting their field. "Right now, the funding climate is quite good, as is the industrial climate for our students," he says. "But I think that even for applied work, there is still a need to increase funding opportunities."