![]()

Departments

![]()

|

Week of 19 February 1999 |

Vol. II, No. 24 |

Feature

Article

David Wong: putting ancient ethical theory to work today

By Eric McHenry

A scholar whose expertise spans 3,000 years and as many miles is this year's John N. Findlay Visiting Professor of Philosophy at BU. David Wong, an authority on both ancient Chinese and contemporary Anglophone philosophy, comes to the University from nearby Brandeis, where he holds the Harry Austryn Wolfson Professorship.

Wong will give the annual Findlay Lecture, part of the Institute for Philosophy and Religion series, at 4 p.m. on Thursday, February 25, in the George Sherman Union Conference Auditorium. His semester-long appointment also entails the teaching of two courses, Introduction to Ethics and a upper-level seminar called Types of Ethical Theory. The syllabus of the latter juxtaposes work from the ancient Chinese tradition and more recent Anglo-American thinking. With a reading list that borrows equally from Mencius and John Mackie, Wong asks students to consider the creation and modulation of human morality.

|

|

|

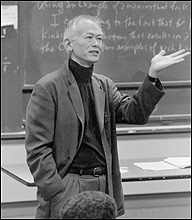

David Wong addresses a large section of Introduction to Ethics, one of two courses he teaches as this year's John Findlay Visiting Professor of Philosophy. Members of the University community at large can hear him speak on February 25 when he delivers the Findlay Lecture, Fragmentation in Civil Society and the Good. Photo by Fred Sway |

Wong first became interested in comparing the two traditions as a graduate student at Princeton University, where he received his Ph.D. in 1977. His early training had been in Western and especially modern Anglophone philosophy, and he was intrigued to discover, in ancient Chinese writings, themes that stretched across the millennia.

"What struck me about Chinese philosophy when I began studying it in earnest," he says, "were the similarities in concern. There is in both traditions, for example, an explicit attention paid to processes of moral development -- to its dependence upon having the right sorts of people around, the right sorts of teachers, the right sort of context in which a person can learn to apply values and norms. The Confucians knew very well that those things can't be learned solely in the abstract. One has to see their application to particular situations."

As a philosopher, Wong's original work has shown a similar interest in putting ethical theory to practical work in the present day, Griswold says.

"His writing and thinking have also been much concerned with issues of special contemporary importance," he says, "such as those of personal and cultural identity: how to establish and defend moral community in the face of the often radical differences among and between outlooks and cultures."

Wong says he plans to treat precisely that dilemma in his Findlay Lecture, Fragmentation in Civil Society and the Good. The heterogeneity of 20th-century America provides the perfect springboard, he says, into discussion of the tension between community and pluralism and of ways to reconcile it.

"I'll be addressing the needs, in a society such as ours, to accept a considerable degree of moral pluralism on the one hand," he says, "and to foster a shared commitment to values that support democratic institutions on the other." Voting, Wong will contend, is one example of an institution that affirms both the e pluribus and the unum of American society. It is of particular value in this regard, he says, not because it is a means by which individuals advance their political prerogatives, but because it is a ritual.

"Ritual is a very important vehicle for moral development in the Confucian tradition," he says. "I'll be suggesting that there's something about rituals such as voting that can help harmonize while at the same time preserving the significance of pluralism."

The excellence of Wong's research and teaching in ethical theory, comparative ethics, moral psychology, and Chinese philosophy has been recognized with fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the American Council of Learned Societies. Wong has held other distinguished visiting professorships, at the University of California-Irvine and at Wellesley College. Such credentials make him an ideal selection for the Findlay Professorship at BU, Griswold says. According to department literature, the chair "bears the name of one of Boston University's best-known philosophers," and "contributes to the recognition of the philosophy department as it continues to build upon its history of comprehensive philosophical inquiry, which is nowhere better exemplified than in Professor Findlay's life and works."

For more information about the Findlay Professorship and Lecture, visit http://www.bu.edu/philo/ centers/ipr/IPRsched.html.