![]()

Departments

![]()

|

Week of 22 January 1999 |

Vol. II, No. 20 |

Feature

Article

Historian dishes out object lessons in consumer culture

By Hope Green

Visitors to the Bay State Road office of Regina Blaszczyk, CAS assistant professor of history and American studies, have mixed reactions to the bric-a-brac adorning her shelves. Some are taken with the collection of ceramic novelty teapots from Woolworth's, the pink tinted-glass ballroom shoe, and the weathered Victorian porcelain. "Other people," says Blaszczyk, knotting her forehead, "get this furrowed brow, turn away, and start looking intently at my books."

|

|

|

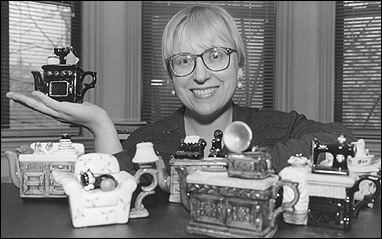

Regina Blaszczyk, assistant professor of history and American studies, with some of her five-and-dime specials from Woolworth's. The teapots are fashioned in such shapes as a Victrola and an overstuffed chair. Photo by Vernon Doucette |

During the past two decades, such items have become the focal point of numerous scholarly studies and museum exhibitions. According to Blaszczyk, these relics hold clues for academics documenting how business has responded to our tastes and preferences through the generations. They reflect the psyche of the consumer in different eras, the identities we have hoped to project, the changing ways we have defined class status. "Consumerism," Blaszczyk says, "is gaining recognition as an important framework for analyzing American history."

By trade, Blaszczyk is a historian of U.S. business and culture, but she says her work is informed by art history, anthropology, and sociology. She brings this interdisciplinary approach to a GRS doctoral seminar she teaches called American Material Culture, and to a survey course and special-topics elective for undergraduates. She is also associate director of BU's American and New England Studies Program (AMNESP).

Both the seminar and Blaszczyk's book pay special attention to Josiah Wedgwood, the 18th-century ceramics artisan and entrepreneur. "Wedgwood," she explains, "came of age at the moment when British society was changing, and there was an emerging middle class with disposable income that yearned to emulate the aristocracy." Wedgwood and other manufacturers capitalized on this trend, she says, "and by responding to the public desire for beautiful things, for objects that displayed status or class, helped to lay the foundation for consumer society as we know it today."

Imagining Consumers relates the tribulations of china and glassware tycoons in their contest for the hearts of working and middle-class women, who made up more than 80 percent of those buying mass-manufactured goods by the 1920s. The title refers to the makers' attempts to sort out consumer priorities and tailor their products accordingly.

Two cheers for

materialism

Topics in the book are echoed in the Material Culture

seminar, which addresses the influences of business and

technology on the evolving middle class. The course also

looks at the history of household product design. Blaszczyk

integrates consumer theory into the undergraduate survey

course as well. "It helps bring history alive for my

students," she says. "I explain to them that their desire

for nice cars and nice clothing is no different from the

desires of 19th-century men and women, and that materialism

is an important part of American life."

Aside from her writing and teaching, Blaszczyk works with AMNESP Director Bruce Schulman to create internships for doctoral students at local and national museums, archives, and historical sites. One intern, third-year student Elysa Engelman, is tracking down information on antique New England needlework samplers for a future exhibit at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem. During her last two summers working at the Old York Historical Society in York, Maine, she conducted research at the home of Elizabeth Perkins, a civic-minded socialite in the early 1900s.

Other students have been placed at the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, the Museum of Fine Arts, the Massachusetts Historical Society, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. "This program really gets BU's name out there, so it strengthens our links to the museum community," Engelman says.

Until now, the intern program has been informal and supported by a large gift from an anonymous donor. Beginning in the fall, however, BU and the Museum of Our National Heritage in Lexington will cosponsor one student stipend annually at the museum under the new Guy O. Matthews Fellowship. Each intern will work with an exhibitions curator one day a week during the academic year and more extensively in the summer.

Cinderella's vehicle

Blaszczyk, who arrived at BU in 1995, worked at the

Smithsonian National Museum of American History in

Washington during the 1980s. She earned her master's and

doctoral degrees in history from the University of Delaware

and holds an additional M.A. in American civilization as

well as a B.A. in art history. An article she wrote for the

book His and Hers: Gender, Consumption, and Technology,

edited by Roger Horowitz and Arwen Mohun (University Press

of Virginia, 1998), uses the story of Cinderella as a

metaphor for the kind of personal transformation consumers

seek by obtaining status vehicles and distinctive clothing.

Thus the glass Cinderella slipper on Blaszczyk's shelf is not just your garden-variety knickknack. Neither are the antique trade cards imprinted with images of fluffy kittens, religious figures, and smiling babies enjoying Eagle brand condensed milk. To the assistant professor, they are symbols of an emerging academic field. Her passion for such things, she adds, might well be rooted in her childhood in Lawrence, Mass., once a thriving mill town. "My father worked a night shift," she recalls, "and every Friday he'd take me to Woolworth's and we'd have lunch at the counter. I was always allowed to buy one item, so I built up a huge collection of ceramic animals and toy cars. Now when I look at the remnants of that collection, a gray elephant and a pink poodle, I often think it must have influenced my interest in pop culture and working-class consumerism."