![]()

Departments

![]()

|

Week of 25 September 1998 |

Vol. II, No. 7 |

Feature

Article

Cycling computer consultant Mark Hagen

Like high-velocity chess

|

|

|

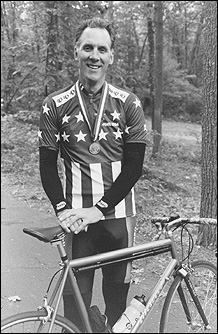

Mark Hagen |

Pain brought him to his knees -- his knees brought him to cycling.

Mark Hagen, winner of the Men's 45-49 Division Criterium race at the Masters National Cycling Championship in July, once enjoyed running. But after college he began to have trouble with his knees. Hagen became interested in cycling when he saw a friend, who was on a U.S. national cycling team in the mid-80s, at one of her races. "I thought it looked like fun," he says. He is now committed to cycling, but he emphasizes that it is only one part of his life.

"I'm not a cyclist," he says. "I cycle." For professional racers, biking can be consuming, but Hagen wants to leave time for other interests as well; for example, his profession. Hagen's official title at BU is lead microcomputer consultant. "I have to be technical," he says. "I have to be business-savvy, and I have to understand basic business processes."

Although he and his coworkers are united in their efforts, Hagen is often called upon to be the front man at formal presentations. However, there are days when he is required to be less formal. "Like today, I dress down to schlep a computer around and set it up in a new office or crack a case to fiddle with memory chips," he says. "Or I might be involved with business systems analysis, where, for example, the Office of Photo Services needs to track all their shoots. I've helped Photo Services and other offices automate. I know nothing about what they do, but I learn."

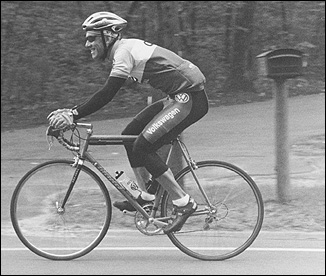

In his job and in racing, variety and teamwork are the appeal for Hagen. He and his teammates are called CCB International; their sponsors are Eastern Bank, Volkswagen, and Marblehead Cycles. "On our team there is an engineer, a bike shop owner, an accountant, the dean of a boys' prep school, and a guy who works with troubled teenagers," he says. " And we get together with other teams, too." Such friendships are essential to Hagen. "If cycling weren't a team sport, I don't think I'd do it."

Even with the support of a team, members must do their own conditioning. "Racing is something like chess: there are well-defined opening and end-game moves, but in between the strategies are dynamic and fluid," Hagen says. "In addition to tactics in racing, there are climbing and sprinting. And there are different disciplines." Leaning forward, he explains, "Within the category of road racing, there are long races -- some from 90 to 120 miles for professionals. Road races for guys like me are 50 to 70 miles; these test endurance primarily, as opposed to speed.

"Criteriums are shorter, less than a mile typically, and in a downtown setting," he continues. "Usually they're a couple of city blocks. Racers go around corners every four to five seconds. This kind of event requires that racers really know how to handle a bike.

"In Time Trials you have to go from point A to point B as fast as possible. Aerodynamics play a great part here. This is where you see disk wheels, tri-bars (triathlete bars), and racers wearing funny hats. It's you against the clock."

In the Masters Championship time trial held in Tallahassee, Fla., Hagen placed third. "Turns out I had missed second place by three seconds. Three ticks of the clock!" he says. "Even so, I was satisfied with my ride. Could I have gone three seconds faster? Absolutely. No doubt. Anybody could have. But I didn't. Time trialing is a good lesson in reality-checking."

Time trialing gave Hagen a reminder of the difficulty that can come with his commitment. After the time trial was over, Hagen went back to his hotel room and noticed that his fingertips were tingling, almost numb. A headache made it difficult for him to focus his eyes. He had eaten only a waffle for breakfast and was certain his disorientation was due to hunger. He and his teammates went for lunch.

But at the restaurant, Hagen was unable to eat. By the end of the meal, his friends were becoming concerned; Hagen asked them to take him to the hospital.

He can't recall many of the details of his experience there, but he remembers clearly the diagnosis doctors gave him after rehydrating him with an IV: he had eaten too little, swallowed too much water, and flushed the electrolytes out of his blood. He fell asleep, still nauseated, and was later awakened by a nurse. "She gave me a shot," he says, "and, in my stuporous state, I thanked her."

He felt better the following day, when the hospital provided him with long-awaited nourishment. "I ate the grilled chicken sandwich -- so much for my vegetarian diet. I knew my stomach would be upset -- along with my conscience -- but I was hungry and knew I needed the protein."

The next day at the race, Hagen finished 16th. "I wasn't very happy with my finish. I had felt tentative and raced that way. My teammate and I finished, rinsed off, and went back to the motel. I was glad to have it over," he says flatly.

Hagen says that the last event, the Criterium, demonstrated his belief that smarts have as much to do with winning as speed and strength. He had been riding with about 50 people. Two pairs were leading their group. Hagen's decision to break away to bridge the gap between himself and the pair trailing the leaders was crucial.

In racing, riders can work together, sharing the lead at intervals to give one another the benefit of an aerodynamic draft. The three of them rode together for a while, leaving only one pair out in front. But when Hagen attempted to work harder to catch up to the lead, the two riders with him swung to the side: the racer's equivalent of not accepting an invitation to dance. "I wasn't going to stick around and conduct in-depth interviews as to their reasons," he says, "so I attacked them. I went alone, and closed in on the leaders."

When Hagen reached the leaders, they too were unwilling to ride with him. "I was starting to get a complex," he says, "so I attacked those two and kept right on going. I was focused on maintaining a good rhythm and going as fast as I could for the last four laps, a little less than three miles."

|

|

|

Mark Hagen, lead

microcomputer consultant for BU and winner of the

Men's 45-49 Division Criterium at the Masters

National Cycling Championship. Photo by Fred Sway

|

When Hagen heard the bell for his final lap, he began to panic. "I put myself in numb-mode," he says. "Even as I crossed the finish line 20 seconds ahead of the pack, I was subdued -- numb from my ride and the realization that I was a national champion."

After a victory lap, Hagen dismounted his bike and was summoned to the announcer's stand where an official shouted the results. Hagen took his place on the top step. "I was handed the National Championship jersey," he says, "but it was a size small! They said it was the only size they had left.

"No matter," he says with a smile. "I squeezed into it."