Gerald Fitzgerald’s poems are “not [just] being said; there is somebody saying them,” the poet Archibald MacLeish wrote in his laudatory foreword to Fitzgerald’s first book, The Wordless Flesh (1960).

Fitzgerald, a College of Arts & Sciences professor emeritus of English and Italian and University Professor emeritus, sometimes labored for months over a single line. But he didn’t seek publication for his hard-fought poetry after Daughters of Earth, Sons of Heaven was published in 1969, says Will Lautzenheiser (CAS’96, COM’07), who became a lifelong friend of Fitzgerald’s after studying with him at BU. “Gerry wasn’t ambitious in that way,” he says. “He thought of his poems as letters to friends and was pleased when they wanted to talk about them.”

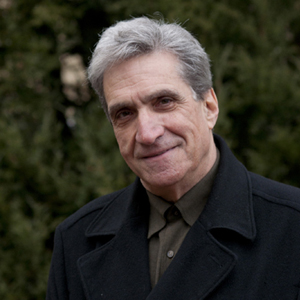

Fitzgerald died on October 25, 2016. He was 86.

After graduating with a PhD from Harvard University, Fitzgerald joined the BU English department in 1963 and his focus turned from publication. He was interim and acting chair of English and of modern foreign languages and literature at different times over the years, and he received a 1974 Metcalf Award for Excellence in Teaching.

Colleagues remember his warmth in welcoming them as new faculty members, his support and friendship, his breadth and depth of knowledge, and his generosity.

Fitzgerald “seemed to have read everything,” says Christopher Martin, a CAS professor of English. “And he would give us insights that made us think again, in a different way, about music, art, humanism as an international movement.” For instance, Fitzgerald, a specialist in Renaissance literature, taught a course on Federico Fellini’s films and strove to foster his colleagues’ appreciation of popular artists like River Phoenix, the Beatles, and Elvis Presley. In a 1991 graduation speech, he explicated passages from Job and the Psalms; an obscure Mozart cantata; poetry by T. S. Eliot, Walt Whitman, and Elizabeth Bishop; and a New Hampshire road sign memorializing a 19th-century hunter and trapper.

Remembering Fitzgerald’s “generosity of spirit,” William Vance, a CAS professor emeritus of English, recalls finding in his mailbox a book Fitzgerald thought would be useful for an upcoming visit to Rome. “Tucked inside were directions to a restaurant on a back street and suggestions about what wine to order and what food. That was typically thoughtful” of him, Vance says. Other colleagues speak of similar mailbox surprises.

Always elusive personally, as retirement approached Fitzgerald seemed to move to “a different sphere,” Martin says. He focused on his flourishing garden: “the most incredible garden,” says Lautzenheiser. “The Fitzgeralds’ backyard was a glimpse of paradise. He was a poet in his garden, too.”

“I loved him,” says Elizabeth McCracken (CAS’88, GRS’88), who capped the courses she took from Fitzgerald with an individual directed study of humor for the pleasure of his company. When they met, he would open a book, then close it quickly, murmuring, “too bawdy,” she says.

“He loved the works he taught and always knew absolutely everything about them,” McCracken recalls. “He was lovely and sweet and shy and funny.”

The opening of Fitzgerald’s poem “A Body’s Snares” offers a glimpse of the private man who wanted others to take life’s joys—but not him—seriously:

You’d think the very least a man

could do

would be accept his body.

Mornings, there

it is…just waiting, peaceful-like.

Should you

Once wake and find it wasn’t

there, you’d care

like crazy, wouldn’t you? What

else would do

one half as well? Why Hell, you’d

be just air

without it.

Thank you for for the Winter/ Spring 2017 Bostonia. I was sad to learn of the passing of Professor Fitzgerald. He was a lovely, brilliant man and a gifted teacher. I want to point out that his distinguished career at BU began in 1963, when I was a student in his freshman English class. One personal memory of that year is that, as a dutiful first year faculty member, he drove to BU from Duxbury in a blizzard, only to find that classes had been cancelled. Edward W. Forbes M.D., CAS(CLA/ MED ’69.