It’s 1 am and BU police officer Nancy O’Loughlin is on the prowl. A sought-after expert on graffiti culture, she patrols by bike, pedaling through the dark alleyways and dimly lit side streets around campus looking for graffiti taggers and the spray-painted evidence they leave behind.

O’Loughlin sees that a tagger who goes by the street name “Why,” spray-painted in curvy, stylized lettering, has hit an alley wall, a dumpster, and a mailbox, all within blocks of the Boston University police station.

She registers dismay. “I don’t know him,” she says wryly. “Yet.”

In more than 30 years on the job, O’Loughlin has arrested hundreds of graffiti taggers, so many that even her enemies know her by name. It is a source of pride that she busted famed street artist Shepard Fairey, who was booked on graffiti charges in 2009 just hours before his work opened in a major retrospective at the Institute of Contemporary Art Boston.

She has made it her career mission to stop graffiti, whether a scribbled tag on a building or an elaborate work of art. Anything done without permission of a property owner is plainly disrespectful, she says. It’s also expensive. BU alone spends tens of thousands of dollars a year to clean up graffiti, and the problem seems to be getting worse.

For decades, taggers have risked serious injury or death spray-painting a wall that runs along a bridge near the commuter rail in the Fenway.

A BU police officer since 2013, O’Loughlin works the midnight to 8 am shift and patrols the area looking for new tags, documenting them, and building her case files.

She is so good at it that police departments around the world, including the New York City Police Department, have sought her expertise. In the 1990s, as a detective lieutenant with the MBTA, she even helped write Massachusetts graffiti laws, which are among the strictest in the nation.

Although in her late 50s and a grandmother, the five-foot-one O’Loughlin plays wing in a women’s hockey league as a way to blow off steam. She also brings to her work a level of bravado that Dirty Harry would admire.

“It’s a big cat and mouse game,” O’Loughlin says, hopping off her bike to study a series of new tags in an alleyway. “And I’m the cat that’s going to get you.”

Graffiti taggers have covered a dumpster in the Fenway area with tags like X-Pils, Blush, and Why, just to make their mark.

Back in the heyday of so-called “trainbombing,” O’Loughlin landed a job as an MBTA transit cop as a recent Northeastern University graduate. Taggers working in the early morning hours could cover entire subway cars with elaborate graffiti, and removing it was costing the MBTA more than a million dollars a year.

When she and a group of other officers found a tagger’s backpack containing a photo of a crew of taggers, the young mother of two decided to make it her mission to identify each one. She did that much the way she still does, she says, by watching closely, talking to people, and putting clues together with shoe-leather detective work. The work can sometimes take years.

“I can’t say how I do it or they’ll know how I figure it out,” O’Loughlin says. “But by the time I’m done building a case, it’s airtight.”

Although their marks might be confused with the graffiti that denotes gang turf, she says, taggers are very often white suburban males, anywhere from the teens to middle age. They throw their name and their designs up on walls, overpasses, and other far-flung places to gain bragging rights on social media and among their peers.

O’Loughlin has had a role in the arrests of some of the most notorious and prolific, among them Adam Brandt, a 27-year-old lumberyard worker from the North Shore who went by the street name Spek. Police believe that Spek, who ran with a crew called Illustrate Total Destruction, was personally responsible for hundreds of thousands of dollars in property damage to buses, trucks, and train cars from Boston to Salem before he was caught in 2009.

And then there was the 2009 Fairey arrest.

O’Loughlin and her longtime partner, Boston police detective Bill Kelley, were part of a team that charged Fairey with more than two dozen offenses after he pasted his work, without permission, on walls around the city, some of them historic properties in the Back Bay.

Because Fairey was by that time a celebrated artist with an international reputation, well-known for his “Hope” poster depicting President Barack Obama, some thought the arrest made Boston seem parochial and out of touch. Boston may be the “only place in America where Shepard Fairey…is not fully feeling the love,” the New York Times speculated. The Boston Globe predicted the arrest would keep artists away from the city.

O’Loughlin wishes the prediction had been accurate. She says she has no regrets about the arrest, although she acknowledges a backlash by some local politicians. “Regardless of what’s put up, if you don’t have permission, what gives you the right?” she says.

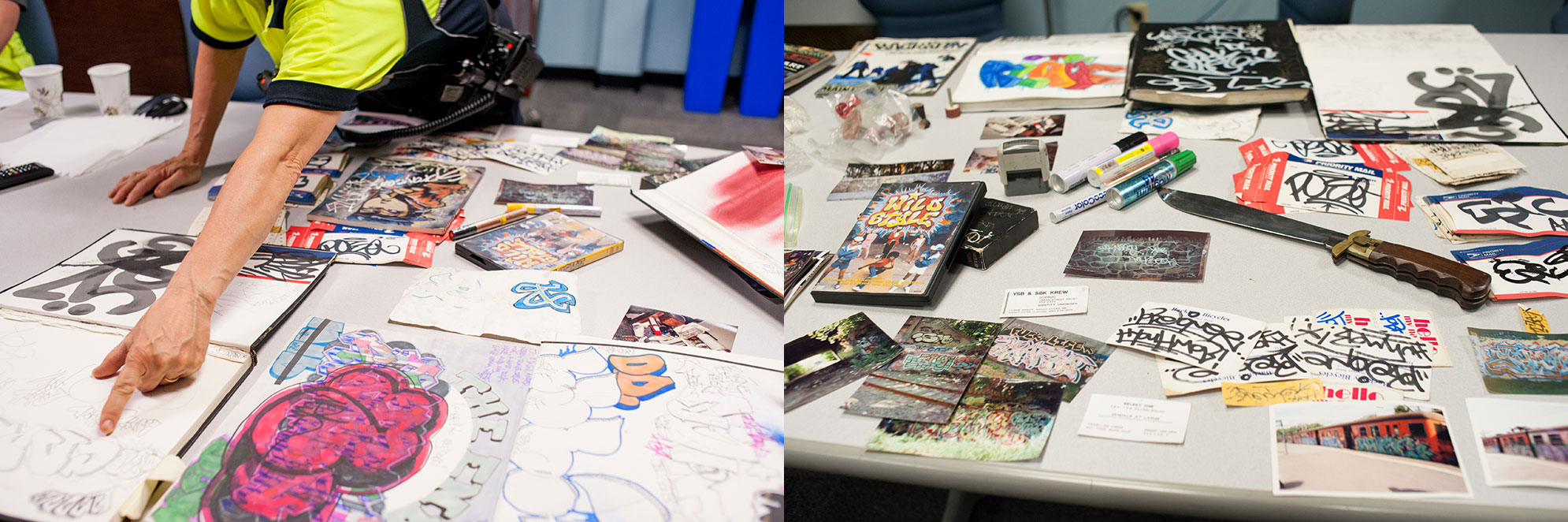

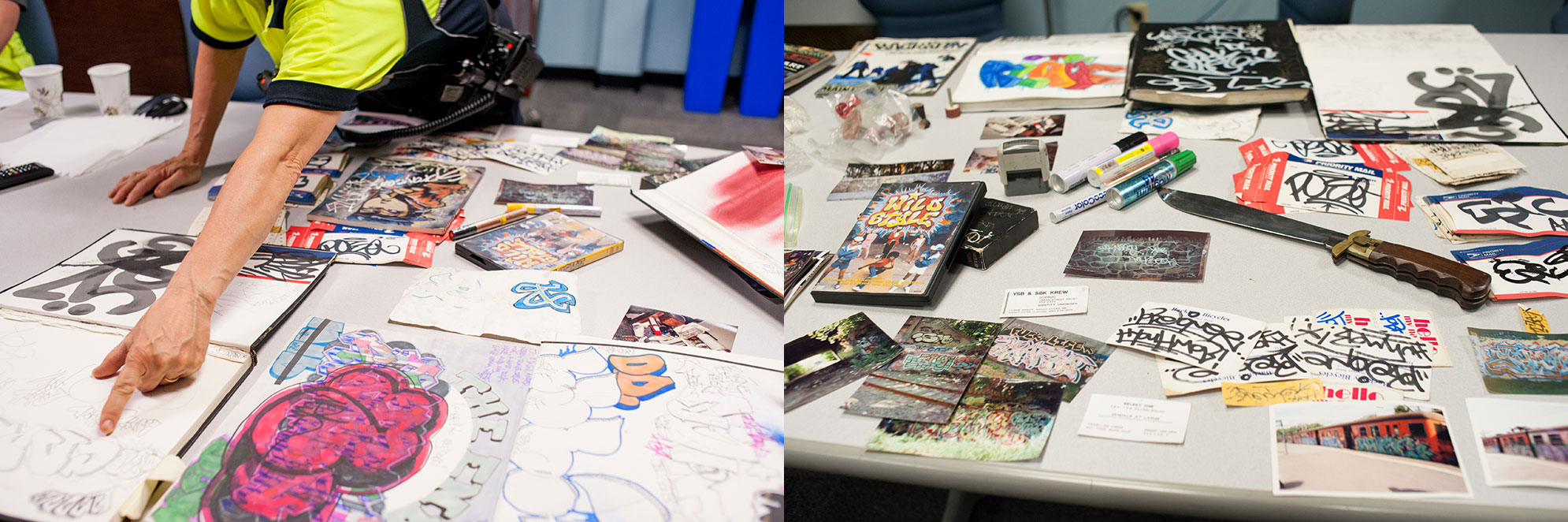

O’Loughlin has arrested hundreds of graffiti taggers since 1983 and has confiscated a massive collection of their materials, including taggers’ sketchbooks, photos of their work, and business cards. Many taggers practice in sketchbooks they call bibles, perfecting their designs in advance so they can execute quickly. O’Loughlin’s extensive confiscated collection fills boxes in the basement of her South Shore home.

Over the years, she has confiscated etching equipment from vandals who carved their name into subway windows. She has a foot-long hunting knife that one of her taggers told her was for protection and the magnets taggers have put in the bottom exterior of their spray-paint cans to silence any sound made by the loose steel pellet within.

Her daughter, Casey O’Loughlin, a BUPD dispatcher, says her mother has earned her reputation because she cares deeply about the community and the people who are affected by reckless behavior. And she is a formidable presence, whether parenting, playing in a hockey tournament, or riding her bike on patrol at 2 am.

“She’s intimidating 24/7,” the 26-year-old says with a laugh.

O’Loughlin could patrol by car, but a bicycle gives her the view from the ground, she says. In fact, she doesn’t even have to focus on graffiti investigations per se. She does it because it’s a public service and she says it keeps her mind and body active.

“She’s always out there looking for it,” says Robert Molloy (MET’91), BU deputy police chief. “It’s a mission for her.”

On a recent night, that mission takes her through a back alley between BU and the CSX rail yard. She rides soundlessly, stopping to examine four large bubble letters in spray paint that appear to spell “YOSA” on a cinderblock wall. “I don’t know this one,” she says.

“But I’d like to meet him.”

Megan Woolhouse can be reached at mwj@bu.edu.

Related Stories

Mozart’s Don Giovanni a Wild Ride

CFA stages a tale of sex and revenge, with a score to die for

Campus Cyberstalking, Drug Arrests Up in 2017, Robberies Down

BU releases annual Clery Act—mandated crime report wrap-up

BU Late at Night, Captured in Photos

From 10 pm to 2 am, the campus hums, with plenty of playing, eating, studying, and sweating

Post Your Comment