When Shana, a young Congolese immigrant living in Lynn, Mass., was 26 weeks pregnant, her baby stopped moving.

Although doctors at nearby North Shore Medical Center (NSMC)/Salem Hospital said the baby’s heart was beating, they were sufficiently concerned to transfer Shana to Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), where doctors performed an emergency C-section.

Baby Adriana weighed one pound 12 ounces at birth and was hospitalized for two months, first at MGH and then at NSMC. The uncertainty was frightening for Shana, but she found solace in music. Erin Peterson, a caseworker at Boston Medical Center (BMC), where Shana had planned to give birth, introduced her to the Lullaby Project, through which several College of Fine Arts alums helped her craft a song for her baby girl.

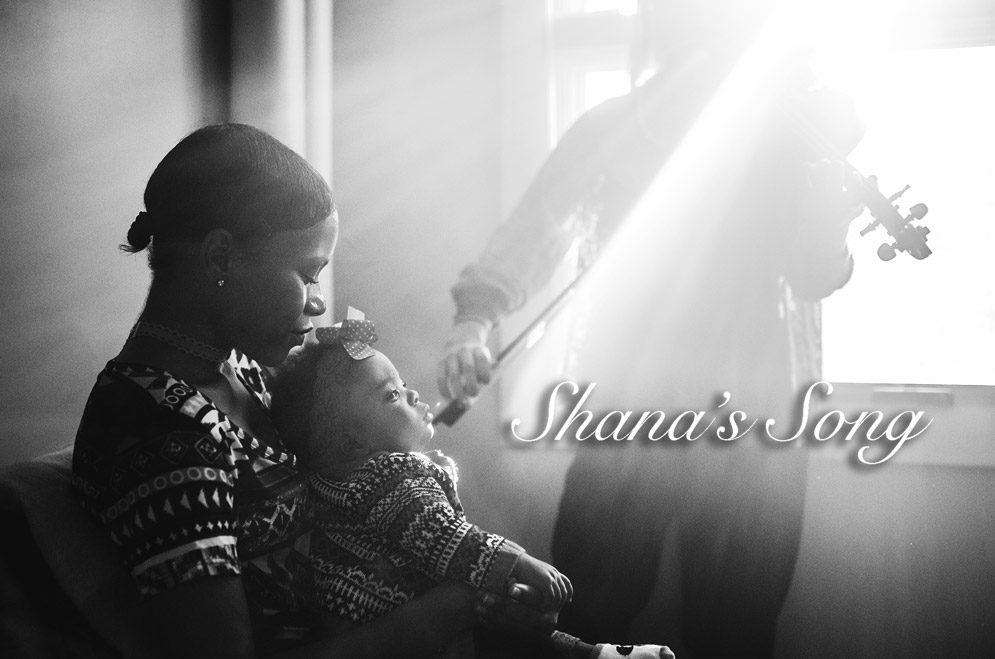

Congolese immigrant Shana (left) worked with CFA alums in the chamber group Palaver Strings—led by violinist Maya French (CFA’15,’18) (right)—to write a lullaby for her baby girl.

Members of the Boston-based chamber group Palaver Strings, known for using their talents for social awareness, have poured their hearts into the Lullaby Project, a national outreach program that helps mothers facing poverty, incarceration, or homelessness create songs—and lasting memories—for their babies.

Led by violinist Maya French (CFA’15,’18), Palaver co–executive director and artistic director, and violist and songwriter Elizabeth “Lizzie” Moore (CFA’14), Palaver Strings has been working for two years with schools and nonprofits in neighborhoods throughout greater Boston. The members base their branch of the Lullaby Project at BMC, where they had an opportunity to work with Moisès Fernández Via, director of Arts | Lab, a unique collaboration among CFA, BMC, and the BU Medical Campus that injects the arts into a clinical setting.

A familiar figure on campus, Fernández Via (CFA’11) has forged artistic partnerships—through the Arts | Lab—at BMC for the last four years, with programs that have had CFA students playing lobby concerts in the Menino Pavilion, providing impromptu solo serenades to patients recovering on BMC’s wards, and reading poetry to cancer patients as they received chemotherapy infusions.

“Palaver Strings has been part of the Medical Campus since the very first day of the Arts | Lab,” Fernández Via says. “I have seen them grow from a casual chamber group to a consolidated string ensemble, embodying the core mission of our task at BMC: turning individual ability into collective opportunities.” The Lullaby Project, he says, “belongs to a category of the Arts | Lab project called ‘Audienceless.’ Here, we test our capacity to include others in what we do.”

Fernández Via was moved to participate in the project because, as he puts it, a lullaby is more than a song. “A lullaby is a musical fossil, a powerful narrative that encapsulates in a song all the complexities of parenthood: nurture, vulnerability, doubt, uncertainty, hope, resilience, tenderness,” he says. “Inviting young parents at risk to write personalized lullabies seems to me a powerful opportunity: a chance to awaken their innate wisdom, so that it guides them through the vastness of parenthood.”

Maya French leads the Boston branch of the Lullaby Project, a national outreach program that helps at-risk mothers create songs—and lasting memories—for their babies.

Fernández Via recruited three participants through caseworkers at BMC. The musicians worked with Shana, then 20, while her baby was in the neonatal unit at NSMC/Salem Hospital. The second participant, Erina, learned she was pregnant at age 40, soon after she arrived from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Marle, a Congolese who befriended Erina in an ESL class while both lived at a Dorchester shelter for new immigrants, went to the BMC session with Erina for moral support and decided to participate in the project. She wrote a lullaby for her mother, who had stayed in the DRC.

French and Moore surveyed the participants, asking about their backgrounds and concerns. For example, they asked, when your child is 18, how will you explain the project and why you participated? What do you do to create calm in your child’s daily life?

Two musicians worked with each woman to develop a custom lullaby. Matthew Brady, from the Boston-based band Milk, who attended BU, served as producer, recorder, and percussionist. Palaver cellist Nikolai Renedo, co–artistic director and community engagement coordinator, was the Spanish translator. Fernández Via translated Marle’s interviews from French to English during the songwriting process.

“We had the moms write a letter to their baby, and used that as a starting point,” French says. With the help of the letter and evaluation, the musicians pieced together the women’s stories, passions, and concerns for their children to develop a tune unique to each. Shana, who had a toddler at home while caring for her newborn in the neonatal unit, says she uses music and poetry to cope with life’s hardships.

“A lullaby is a musical fossil, a powerful narrative that encapsulates in a song all the complexities of parenthood: nurture, vulnerability, doubt, uncertainty, hope, resilience, tenderness,” says Fernández Via.

“I like poems, so I wrote one that they helped me put to a melody,” says Shana, whose tune is inspired by the music of American gospel singer Kirk Franklin. “My poem was about how what I went through was scary at first but it ends good.”

“Once you have words and ideas, you begin thinking about the shape of those words,” says Moore. “Sounds have shape, too, so from the lyrics it’s easier to create the tune, beginning with some chords. And often they’ll tell us a favorite song or songs that make them feel comfortable,” so the musicians can use those as a guide. Shana, for example, wanted the song to be upbeat and played a tune she likes on her phone. “She was trying to portray that this baby was a miracle,” French says.

The pair was surprised by how each lullaby had strong, distinct influences. Erina, though Congolese, is a Spanish speaker who had lived in Cuba and created the ballad “Bienvenido Al Mundo” with Spanish lyrics and a Spanish lilt to express her worries about her child’s future.

Marle, who is learning English, wrote her lullaby “Femme De Courage” to her mother in the DRC, in their native French. “Her whole family is in the Congo, including her children,” French says. “She is here hoping to provide more opportunity for her kids, and wanted to write an ode to her mother for her love and support.”

Shana’s song

I was told you wouldn’t make it, the pain I couldn’t take it…. Miracles come, miracles come, miracles come in small packages. I got down on my knees and prayed, asked my God to make a way, a way to take out pain and stress, and replace it with joy and happiness.

Shana’s song, “Mommy’s Miracle Baby,” written in English, is American R&B, chosen for her love of the upbeat sound.

The all-day process was done in a BMC conference room and was followed by a recording session at Fernández Via’s apartment. Often the songs created through the Lullaby Project are recorded by professional singers, “but we want to encourage the women to sing their own songs,” French says. “These were their lullabies, and as long as they felt comfortable we felt they should have ownership, so when they play it for the baby, the baby hears his mother’s voice. We wanted them to be at the center of it.”

At first the women “were a little nervous, but we tried to keep it really relaxed,” French says. “It was such a new experience for them.” The musicians—instrumentation included upright bass, cello, viola, keyboards, guitars, and some background vocals—performed within the mothers’ vocal comfort zones so they could sing the lullabies easily and naturally. “It’s really for the women and their babies,” says French.

Despite her shyness, Shana sang her lullaby in front of an audience at an April 2016 Arts | Lab event, a stunning moment for her and for the musicians, who remain in touch with her. Her song acknowledges a debt to God for her baby’s survival.

Shana sang solo, and she was nervous about singing in front of people, she says, “but I wasn’t scared. I sang in a church choir in my country.” French says the 30 people gathered in the BMC lobby were swept away by her song. She had dressed up for the event and had posted about it with pride on Facebook. “She’d practiced the song a lot,” French says. “I cried when she sang.”

To help new mothers craft songs that their children are likely to sing to their own babies one day “was one of the most amazing creativity experiences,” says French. “We really bonded with them.” The mothers said they, too, hoped the songs would be passed along to future generations, “hopefully in a better place,” and in a better situation, with their kids having what they need in life, she says. Shana sings her lullaby to Adriana, who is fine now. Her words, set to music, “should give other mothers hope.”

Listen to the lullabies

Track 1: Erina learned she was pregnant at age 40, soon after she arrived from the Democratic Republic of Congo. She created the ballad “Bienvenido Al Mundo” to express her worries about her child’s future.

Track 2: Marle, a Congolese immigrant, wrote the lullaby “Femme De Courage” for her mother, who stayed in the DRC.

Track 3: Shana wrote “Mommy’s Miracle Baby” while her daughter was in the neonatal unit at NSMC/Salem Hospital. The song acknowledges a debt to God for her baby’s survival.

Related Stories

Shana’s Song

Musicians help at-risk mothers write lullabies for their babies through BU collaboration

All They Want for Christmas Is You

BU musicians perform their take on Mariah Carey holiday standard

BU Today Sessions: Francesca Blanchard

Singer-songwriter finds expression in two languages

Post Your Comment