Several years ago, Ali Noorani was working as director of public health at the nonprofit Dorchester House Multi-Service Center (now DotHouse Health) in Dorchester, Mass. Among its health and community services were after-school programs directed at kids in the local Vietnamese community. One day, some of those kids got into a fight and were arrested. Their public defender told them to plead guilty and accept community service, and they did—only to discover that as refugees living in the United States legally, they now had a deportable offense.

“That was a moment in a public health context where I realized that the nation’s immigration system was acting in a remarkably unjust way,” says Noorani (SPH’99), who has been executive director of the National Immigration Forum, one of the country’s leading immigrant advocacy organizations, since 2008. “That was a very formative experience for me, seeing at that intersection what needed to be done.”

The son of Pakistani immigrants, Noorani had concentrated in environmental health at the School of Public Health and after leaving Dorchester House, he went on to become executive director of the Massachusetts Immigrant and Refugee Advocacy Coalition.

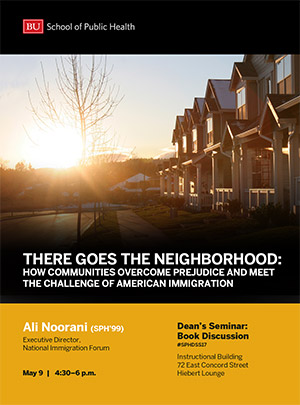

A leading voice on immigration policy in America, he appears frequently on network news broadcasts and has been widely quoted in such publications as the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal. His new book, There Goes the Neighborhood: How Communities Overcome Prejudice and Meet the Challenge of American Immigration (Prometheus, 2017), goes behind the headlines and partisan rhetoric of the fierce current immigration debate to focus on communities around the country that are grappling with the reality of new immigrants and the changing nature of American identity. Noorani discussed his book on the Medical Campus in May as part of the SPH Dean’s Seminar: Book Discussion series.

He traveled the country for the book, speaking to law enforcement personnel, business leaders, faith communities, and immigrants themselves to come up with an accurate portrait of immigration on the ground. From conversations with high school principals, church pastors, sheriffs, and farmers hiring immigrants, he demonstrates how people across the political spectrum are successfully welcoming immigrants into their communities and how the desire for a more compassionate immigration system is much more common than it would appear from the federal debate.

Bostonia spoke with him about the book, where the immigration debate currently stands, and why conservative community leaders can make the most effective immigrant advocates. “Immigration is who we are as a nation,” he says. “It defines our history and shapes our future. To play a small role in helping that happen in a constructive way is just an incredible honor.”

Bostonia: What prompted you to write There Goes the Neighborhood?

Noorani: The basic premise of the book is that the nation’s immigration debate is more about culture and values than politics and policy. Especially in a time like this, when dystopian talking points are lobbed back and forth, I think most Americans are trying to figure out the changes in their neighborhood and what those changes mean to them.

Noorani interviewed nearly 50 faith, law, and business leaders grappling with immigration for his new book.

I feel like there’s a very different story to be told about the immigration debate, a story that includes conservative and moderate faith, law enforcement, and business leaders across the country who are engaging in this conversation in a really constructive way. It’s not Left versus Right so much as it is people struggling with this in a positive way, and that’s just not a story that we hear enough.

How does that constructive engagement play out?

One of the places I wrote about in the book was Spartanburg, S.C. South Carolina has seen the second fastest growth in the Latino population after North Carolina. The history of Spartanburg is one of textile mills, but as textile mills moved to Mexico, it seemed that Mexico moved to South Carolina. What that meant for Spartanburg in particular was that the faith community, educators, and businesses really had to grapple with these changes either in a defensive way or in a constructive way.

Arcadia Elementary School saw this massive increase in their Latino student population, but their principal said, to paraphrase, we’re going to welcome these students, we’re going to make sure that we’re serving their education needs, we’re going to make sure that we’re hiring members of the Hispanic community, and we’re also going to help their parents.

I also sat down with the leadership of the First Baptist Church of Spartanburg, one of the largest Southern Baptist churches in the state, and they were working hard to resettle Syrian refugees—regardless of the refugees’ religion.

Upstate South Carolina is a place where you would think these demographic changes would lead to a very defensive posture, but principals and business leaders and faith leaders were engaging with it in a very constructive way. I’m not saying it’s easy by any means, but they’re willing to take on that challenge.

To have that kind of success, who do advocates need to engage?

Our value proposition is that if you hold a Bible, wear a badge, or own a business, you want a common sense solution to immigration. People see themselves in that message. For the most part, conservatives come to immigration through their faith, through their belief in the rule of law, or their belief in economic prosperity, and it’s a matter of engaging conservatives and moderates on any one or all of those particular messages.

That’s why the pastor, the police chief, and the local business owner are the best leaders of this conversation at this particular moment. Through the book, I interviewed nearly 50 faith, law, and business leaders, and I hope that I was able to give their stories the justice that they deserve, because these are folks who in many ways are ahead of their constituencies, and they’re taking either politically or financially pretty courageous positions.

That sounds like a principle of public health—needing to engage communities, rather than trying to create top-down change.

Absolutely. What I took away from my education at BU is that it’s important to look at the population, at the public, and how the public is interpreting issues, how they’re acting on issues, and ultimately how you make systemic change. That’s how we really try to approach our advocacy at the National Immigration Forum: we want to work with particular constituencies within the public, we want to help them communicate a message that resonates with that particular community that’s struggling with these issues, and ultimately constituency-plus-communication gets us to strategic advocacy. You could make a really good argument that that’s a public health approach to public policy advocacy.

How would you characterize the current immigration environment in the United States—especially since young people covered under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) immigration policy have begun to be deported?

I think DACA as a program is amazing in that it protects 750,000 young people from deportation, but I could also make the argument that it was more important for DACA to lead millions and millions of Americans to realize that their child’s best friend is undocumented, the family one pew over in their church is undocumented, the family down the street is undocumented, and regardless of whether the program continues or if the Trump administration increases deportations, those millions and millions of Americans cannot un-remember that, and that’s a really powerful moment where folks are coming to realize that the undocumented community is part of their community.

How have you seen more conservative communities come to that realization?

I was in Idaho about six weeks ago, meeting with a room of about 75 Idaho dairymen. I would say about 90 percent were Republicans and at least half of them had voted for Trump. To a person, they wanted to see a more constructive and positive approach to immigration, not just because their Latino workforce was a cog in the dairy industry, but because their Latino workforce had been with them for 10 years. These dairymen, by and large white and conservative, saw their Latino workforce as an extension of their family, as an extension of their community, and that is not a sentiment that is reflected by the federal debate.

Whether we’re in Utah or Idaho or Texas or Alabama or South Carolina—really conservative parts of the country—people are seeing the immigrant communities that they live and work with as extensions of their own families in many ways, and I think that’s the sentiment that we need to figure out how to amplify at the local level so it becomes a bigger part of the national conversation. It all goes back to this idea of Bibles, badges, and business.

How do you remain optimistic about immigration when so many view it in negative terms?

I think that voters of all stripes are beginning to understand that what the administration is doing on the immigration enforcement front doesn’t represent their needs and their goals. That’s borne out both in the work that we do and in the polling that comes out almost every week.

The current environment is on the one hand deeply polarized by an administration that I think wants to end immigration to the United States as we know it, but on the other hand I sense there is a growing consensus across the full range of voters that they want a more constructive approach. I’m not going to say that we’re at a tipping point right now—the debate feels really ugly and polarized—but whether through the research for the book or our work and travels every day, my sense is that conservatives, moderates, and liberals are all really looking for a different way on the issue of immigration, and I’m not sure that this administration represents what the majority of Americans really want to see. Let’s just say the Trump administration has provided no lack of teaching moments when it comes to immigration, and people want a different approach.

Michelle Samuels can be reached at msamu@bu.edu.

Related Stories

How the AIDS Crisis Became a Moral Debate

CAS prof’s new book, After the Wrath of God, traces the evolution

POV: Immigration Ban Hurts Universities, the Economy, Society

Trump’s executive order is morally wrong, says BU president

Trump Immigration Ban Spurs Anxiety and Confusion

President Brown’s letter to BU community says executive order “diminishes our nation”

Post Your Comment