Hospitality Management: Learning, Doing, Knowing

By Christopher Muller

On the first day of my HF 100 Introduction to Hospitality Management class I present a lecture that raises the question, “How Do You Teach Hospitality?” It’s my first Power Point slide and is then repeated as my last slide for the day. I suspect (maybe hope) that this question is at the front of the minds of the thousands of people who daily think about hospitality education, training, management and leadership.

In his book, Setting the Table, restaurant icon Danny Meyer (2006) notes that his company, Union Square Hospitality Group, looks to hire individuals he calls the “51-percenters.” These are people who show a positive balance of 51 to 49 percent between emotional skills and technical excellence. The five core emotional skills which USHG looks for are: Optimistic Warmth; Intelligence (defined as insatiable curiosity); Work Ethic; Empathy; and Self-Awareness/Integrity. He notes that:

Emotional skills are harder to assess, and it’s usually necessary to spend meaningful time with people—often in the work environment—to determine whether or not they are a good fit. But it’s critical to begin by being explicit about which emotional skills you are seeking.

It should come as no surprise that emotional skills are not easily imbedded in a modern university business curriculum, which is the academic realm where Hospitality Management programs most often reside. Yet many hospitality management students appear to bring with them a tacit knowledge of these emotional skills when they begin their studies. After more than three decades of watching hospitality students mature I would say that they certainly exhibit strong emotional skills when they head out for a new career. Where then does this knowledge, or alternately, way of knowing, come from?

Is there something distinct about the traditional Hospitality Management curriculum? First offered in 1893 at the Ecole Hoteliere Lausanne in Switzerland and launched in the United States at The School of Hotel Administration at Cornell University in 1922, has this course of study evolved over time to focus on both of Meyer’s skills – originally based on technical skills but now transforming to emotional skills?

A good place to start our inquiry may be to determine this: is Hospitality Management an academic discipline, suggesting it is something which can be codified, written down, and learned by explicit means? Or as some educators note, is it better described as a field of study which dwells in the realm of tacit learning and requires extensive personal contact, experience and observation but may not be adequately articulated by verbal means? How is knowledge managed by teachers, practitioners and students of the industry?

Next we should consider how innovation is applied in the practice and study of hospitality. Is the industry built on the sustaining innovation of measured small improvements in quality and process or on the disruptive innovative introduction of completely new products and services unlike any others which have come before?

On another dimension, we must add a component on the process of thinking and decision-making in hospitality management. Which parts of the business are more intuitive, heuristic and built on gut-feeling and which are more iterative, objective and built on quantitative data analysis?

And a fourth area may be included, how students and practitioners learn. For example, at which point in the education process is it more desirable to have a convergent, fact-based and systematic perspective leading to a single solution, and which point is more likely to reward a divergent, multiple-option perspective where there may be more than one creative or “correct” answer?

This paper presents a model using each of these well-regarded theoretical constructs in an attempt to advance the discussion and answer the question, “How do you teach hospitality?”

Tacit and Explicit Knowledge

Michael Polanyi (1958, 1966) suggested that knowledge could be segmented into two different realms, tacit knowledge and explicit knowledge. His seminal work focused on tacit knowledge and “tacit knowing” which he suggested requires a personal involvement at the individual level of learning. Tacit knowledge is acquired in a non-verbal, observant or experience-based way. It is the knowledge where “we know more than we can tell” to others, or possibly even to ourselves. Harry Collins (2010) expanded the definition of tacit knowledge to include three areas, one involving the relational nature of human social life, one including the autonomic nature of the body and one in the collective nature of society.

Common examples used by both men to explain tacit knowledge include learning to ride a bicycle or to play piano – thinking about the details of the process often leads to not being able to perform at all. Reading a book about riding a bicycle will not lead to winning the Tour de France nor will a manual about finger placements in C# scales turn one into Vladimir Horowitz, no matter how long the study. But months riding a bike through the French Alps with a professional coach or taking a Master Class with a professional musician may in fact lead to personal success. Observing the “embodied knowledge” of experts in a manner which involves personal contact, regular interaction and trust may create tacit knowledge in the observer.

While tacit knowledge is non-verbal, practical and experience based, explicit knowledge is articulated, codified, and language based. It is more deductive and logical. Another characteristic of explicit knowledge is that it can be collected in a single place to be accessed by both individuals and groups (a library, Wikipedia, or a smartphone app should come to mind).

Tacit knowledge is the accumulation of individual “know-how” while explicit knowledge is the fact-based aggregation of shared “know-that.” Collins points out that tacit knowledge is a prerequisite for explicit knowledge, you need to know something before you can explain what it is that you know. Yet the powerful human tendency to share our knowledge, to write things down, to articulate the non-verbal lesson is at the heart of all education, and is also the driver for automation, digitalization and emerging artificial intelligence technology.

Students who are enrolled in an introductory Culinary Arts program preparing menus of standard recipes from the Professional Chef textbook can be said to be using the explicit knowledge of cooks. Students who are engaged in a rotational Stage with the chef at a 3-star Michelin restaurant who exhibits grace and timing under pressure are mostly experiencing tacit knowledge. Both types of knowledge are necessary in learning to be a cook, one articulated and one individually experienced.

Sustaining and Disruptive Innovation

Dr. Clayton Christianson originally proposed the popular management theory of “Disruptive Innovation” in a 1995 Harvard Business School article. He clearly owes a large debt to Joseph Schumpeter (1942) and the concept of capitalism being built on “creative destruction.” The current model presents a framework for the creative process in business formation and innovation. Christianson lays out the differences between the iterative improvement he terms sustaining innovation and the discontinuous offering of the next new thing he terms disruptive innovation.

Sustainers are the well established and typically market dominating major players in an industry. They maintain their leadership position by keying on the needs of their best and most profitable customers. They accomplish this by seeking continuous improvement of products and services they already have on offer. There are many observers who rightly point out that this form of innovation has a significant track record of success, the “standing on the shoulders of giants model” of accretive progress.

The disruptors in business thrive most often when they are technically simpler, cheaper, faster or easier than the established previous generation of products and services they aim to replace. The risk is that these same attributes are often also of inferior quality and therefore have a short, volatile, and vain-glorious impact on the industry they seek to change. But it is the disruptors, like a thunderstorm providing both the destructive potential of a lightning strike and the torrential rain that leads to new growth, who give us the energy to renew and revitalize an industry.

The incumbents maintain their market positions when customers are seeking incremental innovations to existing products or services that are already perceived as being of higher quality. These sustaining innovations are often associated with the phrase “new and improved” although by definition nothing can truly be both new and improved. In many cases step-wise improvements are more likely to find market acceptance than the disruptive newcomers, though the “blue ocean” mindset does keep the capital markets constantly looking for the next new thing just over the horizon.

In business education and practice much has been made of the process of Total Quality Management or the principles of Six Sigma. The step-wise improvement known as the Deming Cycle is another example of the application of sustaining innovation in the classroom. The disruptive innovation of Strategic Management, Principles of Social Media Marketing, or the study of charismatic Leadership styles, all where the new is a positive addition to the topics, also fit well in the Hospitality Management curriculum.

Heuristic and Iterative Thinking

The Nobel laureate economist, Daniel Kahneman, wrote Thinking Fast and Slow (2011) to detail the different modes of thinking used by humans, modes that he termed System 1 or “Fast Thinking” and System 2 or “Slow Thinking.”

Fast thinking is automatic, intuitive and associative. The process comes to the surface in the human tendency to create heuristic mental programs based on previous experiences, rubrics or tested frameworks. An Affect Heuristic decision is made quickly using judgments based on little more than feelings of liking or disliking the object or situation. An Availability Heuristic is quickly made on the desire to find meaning and patterns using information fit into the immediate present situation. In both cases the mind finds a best decision by rapidly relying on relevant past experiences or situations that seem familiar and similar to other successful past decisions.

Slow thinking is controlled, iterative, systematic, or what Kahneman termed “statistical.” This is the decision-making style where thinking about a topic requires attention to detail, focus, and a narrow field of vision. Each new decision, and the thoughts associated with it, is built on the structures of previous decisions in an arduous step-wise process. Slow thinking can be easily disrupted when attention spans are cut short, but it is the balancing counterweight which keeps humans from acting impetuously or in an antisocial manner.

Students in a course learning about Entrepreneurship may be called upon to work in small groups “brain-storming” new concepts for their final project. In another course they may be using business case studies where they will come to trust their gut feelings for identifying the best possible alternative from a broad selection of outcomes. First year students who take Accounting 101 which then leads in year two to Accounting 201 and so on are engaged in an iterative learning process. A doctoral dissertation is the ultimate example of a controlled, systematic and step-wise model of new knowledge creation.

Convergent and Divergent Learning Perspectives

The theorist J.P. Guilford (1967) offered a general theory of human intelligence he named the Structure of Intellect. While this complex theory incorporates up to 150 dimensions, part of it describes the learning processes for reasoning and problem-solving, which he termed Convergent and Divergent production. People who solve problems via a convergent strategy are focused on finding a single correct answer (consider a question on a multiple choice test). In many situations, the convergent learner feels most comfortable in a traditional student/teacher role, with data and facts presented to finding one outcome, for example a single mathematical calculation. Convergent learners collect facts, often from a variety of sources, analyze the situation and seek to test for the best feasible or optimal solution.

In opposition to this pattern would be the divergent learner, one able to identify multiple possible options or solutions. Guilford was very interested in the creative process, which he saw as in the realm of divergent production. A divergent perspective might draw an individual to the arts and humanities, creative writing, or history (where multiple perspective need to work together to find broad solutions) as opposed to science, technology or math as a course of study.

For the Hospitality Management major, convergent production might be seen in fact-based introductory or survey courses, the proscriptive side of Hospitality Law, or in the financial skills associated with an MBA curriculum. The divergent production side might best be embedded in courses with a fluid or “what if” set of answers, including Communications, the self-reflective analysis after an internship or work study program, and the group process.

The Amalgamated Model

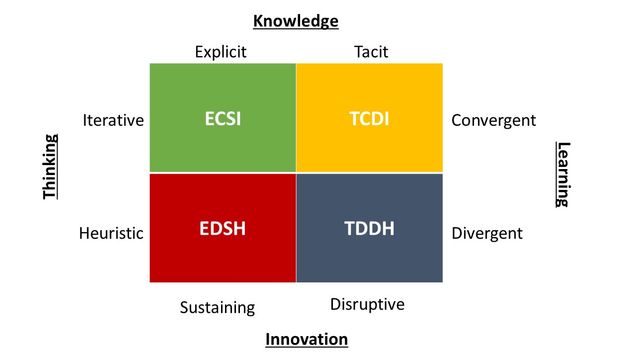

In order to use these theories in a comprehensive way, an Amalgamated Model (Figure 1) can be formed into a rubric using each of the four key competencies on alternating sides of a two-by-two matrix. Knowledge is either Explicit or Tacit, Learning is Convergent or Divergent, Innovation is Sustaining or Disruptive, and Thinking is Heuristic or Iterative. The corresponding quadrants each then suggest a different means for evaluating a Hospitality Management curriculum.

The Quadrant Profile

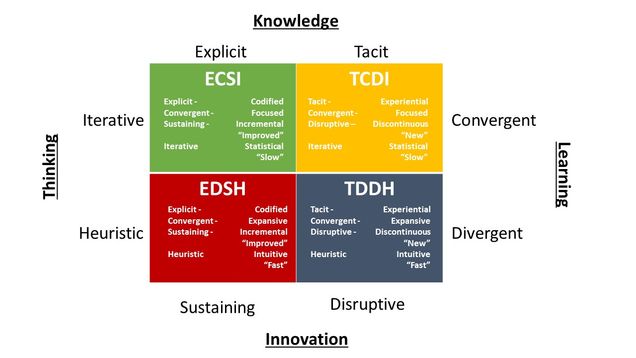

Expanding on the basic model (Figure 2), each quadrant suggests a teaching/learning viewpoint with specific weight placed on different emotional and technical skills. The ECSI quadrant would reward a codified, focused, incrementally improved and statistical (slow) set of learning objectives. Quadrant two encompassing the EDSH attributes would look for codified, expansive/creative, incremental and intuitive (fast) offerings. The third Quadrant with a TDDH mix encourages learning in an experiential, expansive/creative, discontinuous new and intuitively fast manner. The final TCDI quadrant would involve an experiential, focused, discontinuous new and statistical (slow) combination.

Application to the Hospitality Management Curriculum

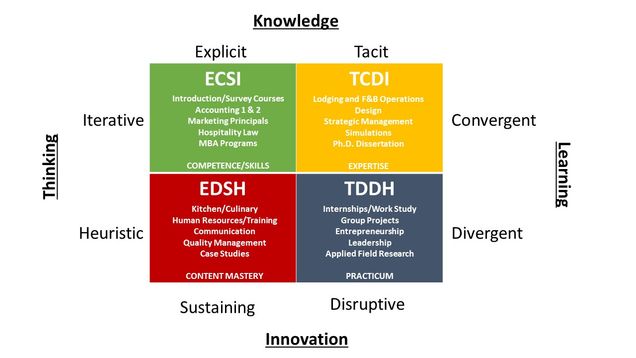

If we consider the traditional Hospitality Management curriculum (Figure 3), both required and elective courses, and look at the entire range of educational levels, from undergraduate to doctoral studies, the Amalgamated Model can thus be helpful in creating a typology of course offerings.

Quadrant One (ECSI) concerns itself with student competence and technical skills, with courses that build on a core knowledge structure or discipline. Such classes as the Accounting sequence (Financial Accounting, Management Accounting, and Finance), or a Marketing sequence (Introduction to Marketing, Services Marketing, Advertising Communication, Consumer Behavior) fit well here. A case can be made that the core Master of Business Administration curriculum is also focused, stepwise, explicit and data based and is best located here.

Quadrant Two (EDSH) is more the domain associated with concept mastery, still using the accumulated articulated knowledge of specific topical information. The various work done in a kitchen or culinary class, based on the multitude of recipes and cookbooks can be exhibited here. But so can the explicit knowledge written down in the form of industry case studies, where students learn by creating their own system of decision-making heuristics.

In the third Quadrant (TDDH) the practical life experience which students bring with them to class gives them an opportunity to learn by doing. Experiential learning in the form of internships and work study, group projects and brain-storming new business concepts allows them to be creative in a business setting.

The final Quadrant (TCDI) is where students gain the focused perspective that enables a measure of expertise to develop. Whether at the elective/concentration level for undergraduates or the process of undertaking the years long process involved in doctoral studies, this is the time when data and hypotheses are tested, and preconceived notions are challenged.

Getting to 51%

Let’s use the information shared by Danny Meyer in the quote from above but parse individual phrases to help reveal how the theories just discussed are informing the discussion:

Emotional skills are harder to assess, and it’s usually necessary to spend meaningful time with people—often in the work environment—to determine whether or not they are a good fit. But it’s critical to begin by being explicit about which emotional skills you are seeking.

Emotional skills, what Meyer uses to determine the attractiveness of the “51%-ers” to a restaurant unit of USHG, are as he suggests hard to assess. These “soft skills” do not come with easily tested variables. But there is also the 49% applied to the technical skills of the work of hospitality to consider. The explicit knowledge learned in first the ECSI and then the EDSH afford the student a way to build up a base shared knowledge of facts, protocols and historical constructs (Figure 4). These courses also establish the foundation of a shared vocabulary, and mastery of skills which will allow them to become part of a broader social environment.

Meyer also suggests that it is important to invest time in each individual in order to highlight the emotional skills his company desires. The slow, iterative process of steady improvement and quality control also appears in the ECSI and EDSH quadrants.

…necessary to spend meaningful time with people…

Also embedded in the Meyer observation is the tacit learning only afforded by an individual, experience based and hands-on set of lessons in the actual work environment. This is the internship model used extensively in hospitality management education.

…often in the work environment…

To make his search uniform and standardized, he acknowledges the need for moving from the highly personalized, but inconsistent system of tacit learning. He suggests, as did Collins, the need to share our learning and expertise by making it explicit, articulated, and language based.

…it’s critical to begin by being explicit about which emotional skills you are seeking…

Finally, although it is unstated in his admonition for all business enterprises to include hospitality in their development, he still requires employees to have the technical skills and clear focus to become experts in their endeavors. Whether it is in the expertise of the Sommelier, the Executive Chef, or the Chief Financial Officer, no great hospitality company can survive without highly skilled and knowledgeable practitioners.

A Return To Our Question

So, as I ask my students, and indirectly myself, “How do you teach Hospitality?” the Amalgamated Model may yield a better chance of finding an answer. Not too long ago hospitality management fit comfortably in the experiential apprentice/journeyman/master craftsman system of observational study. While relevant for the passing along of both tacit and technical skills, this system continues to fall short of the explicit knowledge and fact based needs of a modern business enterprise. Likewise the current effort focused only on financial numeracy and a statistical path to knowledge also falls short in the emotional intelligence necessary to achieve Meyer’s 51% status.

Instead of a curriculum being centered in just one or two quadrants, a more holistic approach, one looking to satisfy the requirements of being competent, conceptual, pragmatic and a content expert may yield a more robust and therefore more rigorous choice for hospitality curriculum design in the 21st Century.

Christopher C. Muller is Professor of the Practice of Hospitality Administration and former Dean of the School of Hospitality Administration at Boston University. Each year, he moderates the European Food Service Summit, a major conference for restaurant and supply executives. He holds a bachelor’s degree in political science from Hobart College and two graduate degrees from Cornell University, including a Ph.D. in hospitality administration. Email cmuller@bu.edu

Christopher C. Muller is Professor of the Practice of Hospitality Administration and former Dean of the School of Hospitality Administration at Boston University. Each year, he moderates the European Food Service Summit, a major conference for restaurant and supply executives. He holds a bachelor’s degree in political science from Hobart College and two graduate degrees from Cornell University, including a Ph.D. in hospitality administration. Email cmuller@bu.edu

Reference Texts

- Meyer, Danny, Setting the Table: The Transforming Power of Hospitality in Business, 2006 HarperCollins, New York

- Polanyi, Michael, Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy ,1958, The University of Chicago Press, London

- Polanyi, Michael, The Tacit Dimension, 1966, The University of Chicago Press, London

- Collins, Harry, Tacit and Explicit Knowledge, 2010, The University of Chicago Press, London

- Christiansen, Clayton, The Innovator’s Dilemma: The Revolutionary Book That Will Change The Way You Do Business, 2011, Harper Business Essentials, New York

- Schumpeter, Joseph, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, 1942, Harper & Brothers, New York

- Kahneman, Daniel, Thinking Fast and Slow, 2011, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York

- Kolb, David A., Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development, 2015, Pearson Education, Upper Saddle River, NJ

- Guilford, J.P. The Nature of Human Intelligence, 1967, McGraw-Hill, New York

23 comments

Really helpful and educational blog. Keep writing and sharing more about such informative topics.

Thanks for your great guidance. this is really very informative post. this site is very helpful for those students who are interested in hospitality field or wants to become a hospitality in magagement. this is very impressive and insightful post. thank you so much for sharing great content.

Daily I visit most of the web pages to get new stuff. But here I got something unique and informative.

Best Dentist In Jaipur

The quality and quantity of work produced here are absolutely informative. Thanks for sharing.

Buy furniture online store

Excellent post. Please keep up the great work. You did an amazing job. I really enjoyed reading this blog. I like and appreciate your work. Thank you for Sharing such an amazing article.

Tempo Traveller in Jodhpur

The topics you share are really meaningful to me, I will regularly monitor your website.

Best Website Development & Designing Company In Jaipur

Its a great pleasure reading your post.Its full of information

astrology consultancy

You have lots of great content that is helpful to gain more knowledge. Best wishes.

Free Astrology consultancy services in India

Manikaran Sightseeing Tour, Manikaran Sightseeing Tour Package, Manikaran Sightseeing Package, Manikaran Sightseeing Taxi, Manikaran Sightseeing Cab

I agree with you, but I can also recommend this alcohol delivery. The guys helped out a lot on last week

مجموعه اصفهان آهن با مديريت سعيد صمصام شريعت (Saeid Samsam Shariat) و فراهم نمودن بستري جديد و متفاوت در زمينهي خريد و فروش و کسب رضايت مشتري به همکاري و تعامل مستمر و بلند مدت با مشتريان ميانديشد. در اين راستا اين شرکت موفق به دريافت استاندارد هاي بين المللي از جمله گواهينامههاي،مديريت کيفيت ISO9001 و رضايتمندي و بررسي شکايات مشتريان ISO10002 گرديده است توانسته به عنوان يک منبع مطمئن، قابل اتکاء و برتر در اين عرصه شناخته گردد.

قيمت ميلگرد آجدار

بازرگانی پلیت استیل یک ، یک فروشگاه و مرکز تامین انواع ورق های فولادی و اهنی صنعتی و ساختمانی ، با تضمین حقوق مشتری و ارسال کالا در سربع ترین زمان ممکن

قیمت انواع ورق فولادی گالوانیزه

Safavid Period (16th–18th centuries):

The Safavid dynasty played a significant role in the development of Persian painting. Rulers such as Shah Tahmasp and Shah Abbas I were patrons of the arts, contributing to the flourishing of miniature painting.

Notable artists of this period include Reza Abbasi and Muhammad Qasim.

Qajar Period (18th–19th centuries):

The Qajar dynasty saw a continuation of the Persian painting tradition, but with some stylistic changes influenced by Western art. Portraiture became more prominent during this era.

Contemporary Period:

In the 20th century, Persian painting underwent further transformations with the influence of modern and contemporary art movements. Artists like Mohammad Ghaffari (Kamal-ol-Molk) and Bahman Mohasses contributed to the evolution of Persian visual arts.

Designs and Patterns: Termeh is known for its elaborate and sophisticated designs. Traditional patterns often include floral motifs, paisleys, and geometric shapes. The designs are created using vibrant and rich colors, making Termeh a visually stunning textile.

Usage: Termeh is used for various purposes, including tablecloths, shawls, scarves, and other decorative items. It is also commonly used for making traditional Iranian clothing.

Cultural Significance: Termeh holds cultural significance in Iran and is often associated with elegance and beauty. It reflects the rich artistic heritage of Persian craftsmanship.

Ghalamkari, also known as Ghalamzani, is a traditional Iranian art form that involves the creation of intricate hand-painted or block-printed textiles. The word “Ghalamkari” is derived from two Persian words: “ghalam,” meaning pen, and “kari,” meaning craftsmanship. Therefore, Ghalamkari can be translated as “pen craftsmanship.”

Key features of Ghalamkari art include:

Hand-Painted or Block-Printed Textiles: Ghalamkari artisans typically work on textiles such as cotton or silk. The designs are created using either hand-painting or block printing techniques. Block printing involves carving intricate patterns onto wooden blocks, which are then dipped in dye and pressed onto the fabric.

تعمیرات ساعت هوشمند شیائومی

تعمیرات ساعت هوشمند شیائومی

persian art painting has a rich and diverse history that spans thousands of years. Persian painting, in particular, has been influenced by various cultural, religious, and historical factors, resulting in a unique and vibrant tradition. Here are some key aspects of Persian art painting:

Miniature Painting:

One of the most renowned forms of Persian painting is miniature painting. This intricate and detailed style emerged during the Mongol Ilkhanid dynasty (1256–1353) and reached its zenith during the Safavid dynasty (1501–1722).

Miniatures often depicted scenes from literature, poetry, and courtly life. They were characterized by meticulous attention to detail, vibrant colors, and the use of gold and silver.

Persian painting also known as Iranian painting, has a rich and diverse history that spans many centuries. It is deeply rooted in the cultural and artistic traditions of Persia (modern-day Iran) and has been influenced by various artistic styles over the years. Here are some key points about Persian painting:

Historical Roots:

Persian painting has its origins in ancient Persia, dating back to pre-Islamic times. However, it underwent significant developments during the Islamic period, particularly during the Safavid dynasty (16th to 18th centuries) when it reached its zenith.

Colors:

Vibrant and rich colors are a hallmark of Termeh. The use of bold and striking hues adds to the aesthetic appeal of the textile. Common colors include deep reds, blues, greens, and gold.

Cultural Significance:

Termeh has a deep-rooted cultural significance in Persian art and is often associated with luxury and elegance. It has been a part of Persian culture for centuries and is used in various traditional ceremonies, weddings, and special occasions.

Historical Significance:

Termeh has a long history, dating back to ancient times. It has been mentioned in historical texts and has evolved over the years, adapting to different periods and influences.

Termeh is a traditional Persian textile with a long history and a significant place in Persian art and culture. It is a luxurious fabric woven by hand and is known for its intricate patterns and vibrant colors. Termeh is often used in various forms, including tablecloths, scarves, shawls, and other decorative items.

Here are some key features and aspects of Termeh art:

Material and Weaving Technique:

Termeh is typically made from natural fibers such as silk, wool, or a combination of both. The use of high-quality materials contributes to the fabric’s softness and sheen.

The weaving technique involves an intricate and time-consuming process. Skilled artisans use a combination of silk and wool threads to create detailed and elaborate patterns.

Termeh is a traditional Persian textile with a long history and a significant place in Persian art and culture. It is a luxurious fabric woven by hand and is known for its intricate patterns and vibrant colors. Termeh is often used in various forms, including tablecloths, scarves, shawls, and other decorative items.

Here are some key features and aspects of Termeh art:

Material and Weaving Technique:

Termeh is typically made from natural fibers such as silk, wool, or a combination of both. The use of high-quality materials contributes to the fabric’s softness and sheen.

The weaving technique involves an intricate and time-consuming process. Skilled artisans use a combination of silk and wool threads to create detailed and elaborate patterns.

Ghalamkari designs are characterized by intricate patterns, often inspired by nature, Persian architecture, and historical themes. Common motifs include flowers, birds, geometric shapes, and Persian calligraphy. The designs are meticulously crafted, showcasing the skill and creativity of the artists.

Color Palette:

The color palette in Ghalamkari art is diverse, featuring rich and vibrant hues. Natural dyes are often used, giving the artwork a warm and earthy feel. The colors may include shades of red, blue, green, yellow, and brown.

Cultural and Historical Significance:

Ghalamkari has a long history in Persian culture, dating back centuries. It has been used for various purposes, including decorating clothing, accessories, tablecloths, and wall hangings. The art form often carries cultural and historical narratives, reflecting the traditions and stories of the region.